Prevention

Modern medicine is increasingly transitioning towards preventive care. This shift towards prevention has also been observed in breast cancer care in recent years, particularly with the discovery of the BRCA gene. Subsequently, multiple genes and risk factors have been identified. Depending on these factors, a personalized screening strategy can be chosen. Therefore, it is crucial to understand these genetic and risk factors.

Diagnosis

I was diagnosed with cancer ... This website serves as a portal designed to assist you and your loved ones in accessing personal information and finding solutions to your concerns.

The primary goal of this website is to offer guidance and support to patients as they navigate their journey toward recovery and improved quality of life. The "Diagnosis" section of our website is divided into two main categories. Firstly, under "Anatomy and Physiology," we provide fundamental knowledge about the breast. Secondly, in the "Tumors and Disorders" section, we delve deeper into various breast-related conditions.

Moreover, we aim to provide information to women who may be concerned about potential breast issues but are hesitant to seek immediate medical advice. Knowledge and information can often offer immediate reassurance if a woman is able to identify the issue herself and determine that no specific treatment is necessary. Conversely, we also strive to educate women who have received a diagnosis of a serious breast condition, such as breast cancer, and wish to approach their doctor well-informed and prepared.

Treatment

The treatment for breast cancer should immediately include a discussion about reconstruction. Our foundation has no greater goal than to raise awareness of this among patients and oncological surgeons. By making an informed decision beforehand, we avoid closing off options for later reconstruction while still considering the oncological aspect. Of course, survival is paramount, and the decision of the oncologic surgeon will always take precedence.

The "Reconstruction or not?" page contains all the information you can expect during an initial consultation before undergoing tumor removal. This page is comprehensive, and your plastic surgeon will only provide information relevant to your situation.

"Removing the tumor" details the surgical procedure itself. This is the most crucial operation because effective tumor removal remains paramount. We guide you through the various methods of removal, a decision often made by a multidisciplinary team comprising oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, radiotherapists, breast nurses, gynecologists, oncological surgeons, and plastic surgeons.

The "Breast Reconstruction" section includes information and illustrations of the different reconstruction options along with corresponding steps.

Revalidation

Those treated for cancer often need a long period to recover.

Cancer is a radical illness with a heavy treatment. Often, people have to deal with psychosocial and/or physical problems afterwards, such as stress, anxiety, extreme fatigue, painful joints, reduced fitness, lymphedema... This can have a major impact on general well-being.

There are rehabilitation programmes offered by most hospitals. We cover some of the major topics here.

Quality of life

Quality of life is a key factor in coping with breast cancer. Therefore, it is important to find coping mechanisms that work, which will be different from patient to patient. For some, it may be finding enjoyment in activities they engaged in prior to diagnosis, taking time for appreciating life and expressing gratitude, volunteering, physical exercise... Of prime importance, studies have shown that accepting the disease as a part of one’s life is a key to effective coping, as well as focusing on mental strength to allow the patient to move on with life. In this section we are addressing some topics that patients experience during and after treatment and we are providing information to address them.

Breast reconstruction

When is breast reconstruction indicated? What are the current breast reconstruction techniques? And what are the pros and cons or potential complications associated with the different breast reconstruction techniques?

I. Breast reconstruction - General

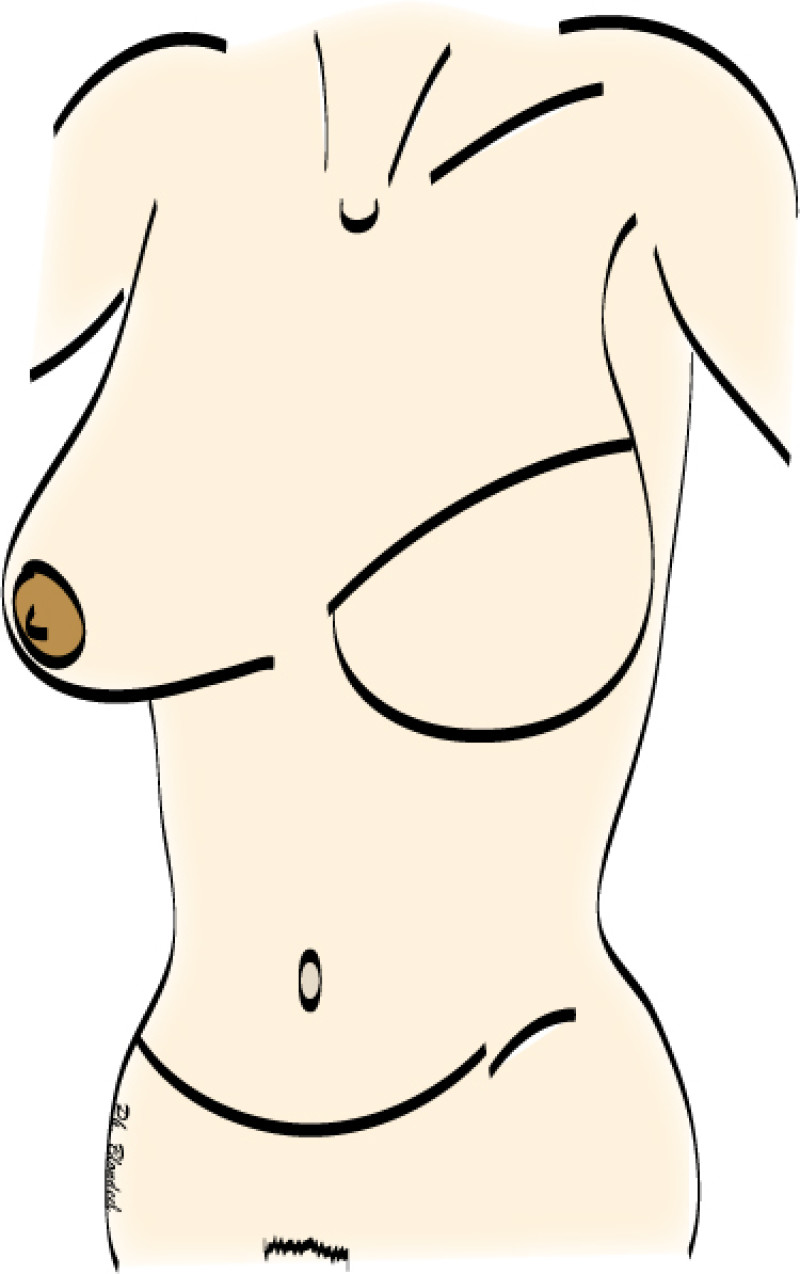

The most common indication for partial or total breast reconstruction is ablative surgery following breast cancer. However, patients with developmental abnormalities (under-development, breast asymmetry, tuberous breast deformity), congenital malformations (breast absence, Poland’s syndrome) or breast deformities following trauma or infection, can also benefit from the same reconstructive techniques as breast cancer patients. Recently, patients with genetic mutations that significantly increase the risk of breast cancer, are forming an increasingly significant group, as precise tools for genetic screening become available.

The obligation of care providers to inform about breast reconstruction

In our opinion, every patient diagnosed with breast cancer or at risk of developing the disease, should be fully informed about the reconstructive options available. Unfortunately, the only country compelled to provide this information to breast cancer patients by federal law is the United States. In many other developed countries, doctors and allied health care professionals provide insufficient information to breast cancer patients due to a lack of training, ignorance or a personal belief that breast reconstruction is unnecessary. Approximately 50 % of breast cancer patients has a strong initial interest in breast reconstruction following ablative surgery. Although approximately half of this group of patients decide not to proceed, the fact the option has been offered, conveys an important psychological benefit.

Detailed information should be provided on all techniques, in particular the differences between reconstruction with implants (or expanders) and reconstruction with autologous tissue.

If a woman decides against breast reconstruction, the other alternatives should be discussed. Wearing an external prosthesis, the advantages and disadvantages of breast conservation therapy and the different types of mastectomy should all be clearly explained.

II. Techniques to surgical breast reconstruction - Introduction

Further below is a list of factors that help decide which technique may be suitable for you. The ultimate goal of breast reconstruction is symmetry between both breasts and these factors help to achieve this.

Factors influencing the choice of reconstruction

The condition of the chest wall after removing part or the entire breast

The following anatomical structures will have an important role to play when considering a reconstruction:

The presence of the anterior axillary fold.

The presence of the pectoralis major muscle.

The quality of the remaining breast skin.

The position and quality of scars.

The presence and / or condition of the nipple areolar complex.

The weight of the patient.

Generally, patients in whom the anterior axillary fold has been damaged, the pectoralis major muscle removed, with poor skin quality, bad scars, an absent nipple areolar complex and who are not very thin, are better candidates for autologous reconstruction. Otherwise, implant based breast reconstruction may be considered.

A small non-sagging breast can be reasonably well reconstructed with an implant. However, patients who will undergo, or who have undergone radiation therapy, are poor candidates for this form of reconstruction. Autologous tissue will achieve superior aesthetic results for larger volume breasts with moderate to severe sagging.

The contralateral breast

What ultimately happens to the contralateral breast (other unaffected breast) is determined by the patient. If she is satisfied with the shape and volume of her contralateral breast, no further intervention is required. However a breast augmentation, breast reduction or breast lift can be performed to improve symmetry.

Additional important factors

The choice of reconstructive technique is also influenced by the oncological requirements of surgery. Wide and extensive resections require reconstruction with microsurgical tissue transfer (free flaps). Post-operative radiotherapy is a contraindication to the use of implants. The logistics and technical capabilities of the plastic surgery team within the multidisciplinary framework are also an important factor determining the selection of reconstructive technique. Finally, patient expectations influence the final decision. Patients with high aesthetic expectations, requesting a stable long-term result will clearly benefit from an autologous reconstruction.

III. Breast Conserving Surgery

Breast conserving surgery causes minimal gland disruption especially if combined with immediate glandular reshaping. However, the subsequent effect of radiotherapy can lead to significant distortion of the remaining breast. The skin and underlying soft tissues of the irradiated area becomes edematous, less vascular and scarred, with a tight, woody appearance. Fibrosis also occurs in the underlying muscles and remaining breast tissue, which eventually shrinks to some degree.

There is a change in both the shape and volume of the breast, which many patients find unacceptable. Although surgery to an irradiated breast is not recommended, the deformity can be so marked that reconstructive surgery, with the addition of well-vascularized tissue from outside the irradiated area, may be necessary.

Since the Milan trials of the early 1970’s there has been a trend towards breast conserving surgery. Modern breast reconstructive techniques were not available at that time and breast conservation was an attractive alternative to the radical or modified radical mastectomy. Unfortunately over the years, this over-enthusiasm with breast conservation has led to many substandard or poor aesthetic results. While the results can be excellent in patients with large breasts, many small breasted, thin women survive their cancer only to be faced with significant post-radiation fibrosis, glandular retraction and nipple-areolar distortion. In particular, wide excisions, of between one-third and one-half of the gland, lead to a poor outcome. Some very good results can still be achieved with breast conservation therapy but patient selection is critical.

The relationship between body mass index, breast size and tumor size is extremely important. Good results can only be obtained, without resorting to local or distant flaps, implants or other tissues (i.e. lipofilling), if less than 1/8 of the total breast gland is resected and primary closure of the defect performed. Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy can also assist in reducing the preoperative tumor size and increasing the number of suitable candidates for breast conserving surgery.

As ablative breast surgeons began to realise that the aesthetics of the breast were important to a woman after her breast cancer treatment, there was a move towards narrower excision margins. Unsurprisingly this resulted in a higher re-excision rate. Without plastic surgical support, it can be difficult to balance excising enough tissue around a tumour to obtain acceptable oncologic margins, with simultaneously preserving the natural shape of the breast. This is particularly true when one considers the challenge of predicting the long-term effect of post-lumpectomy radiotherapy.

Within plastic surgery we possess the reconstructive tools that allow the replacement of total or partial mastectomy defects. We can rearrange the breast gland or introduce new tissue into the resection cavity at the time of the ablative surgery to minimize the severity of contour changes. The availability of plastic surgeons as part of the breast conservation team gives the oncologic surgeon flexibility to pursue wider resection margins without concerns about unacceptable aesthetic results and therefore reduces the re-excision rate. With modern reconstructive procedures we can now provide the same oncologic safety but offer even better breast conserving surgery (BCS). The presence of a plastic surgeon in the breast clinic can therefore influence the way in which an oncologic (ablative) surgeon decides to treat breast cancer.

The wide range of BCS defects encountered by a plastic surgeon is the result of a number of variables including the orientation of the skin incision, the pre-operative breast size, the percentage of breast parenchyma resected, the location of that resection, the intensity and method of delivery of radiotherapy and a patient’s response to radiotherapy.

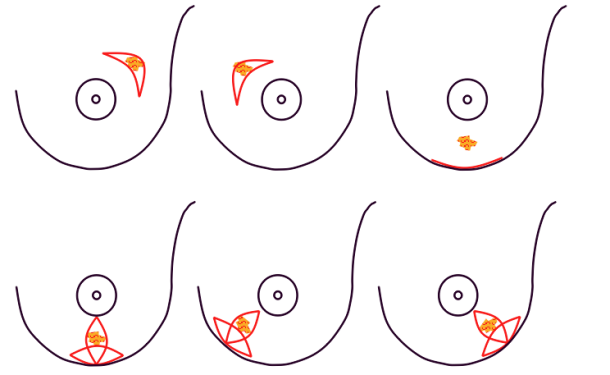

In both breast conserving surgery and a mastectomy, the orientation of the skin incisions are of the utmost importance. In the upper quadrants, circumferential incisions, in or parallel to, the circumference of the areola are recommended, to limit their confines to the area covered by a bra. In the lower quadrants radial incisions are acceptable. In later corrections these scars can be used to further adjust, reduce or lift the breast. The radial incisions can also be combined with a horizontal incision in the inframammary crease (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Preferred incisions for Breast Conserving Surgery according to tumor location, helping to confine scars within the bra lines.

Different reconstructive options are available, depending on the breast volume deficiency following resection or the effects of radiotherapy (table I).

Breast volume deficiency | Reconstructive Option |

< 1/8 | direct closure, local glandular flap or lipofilling |

> 1/8 and <3/8 | loco-regional soft tissue flap from the flank or back, lipofilling |

>3/8 | skin sparing mastectomy and reconstruction with a distant free flap |

The different options

Direct closure: if the remaining breast gland is supple and well vascularized, simple tissue advancement can be used to fill small defects.

Local glandular flaps: small pieces of breast tissue, particularly from the bottom edge of the gland, can be transposed to correct minor defects or contour irregularities. It is a relatively short, simple procedure that leaves inconspicuous scars. This technique is also frequently used to perform a simultaneous lift or reduction of the affected breast (fig.2). Local random patterned flaps often have wound healing problems because of the widespread radiation changes. Sometimes it is therefore necessary to introduce regional or distant, well vascularized, healthy tissue.

Loco-regional soft tissue flaps from the flank or back: if some of the outer quadrant of the breast has been removed, this defect can be filled by moving tissue from the back or flank.

Distant free flaps: skin and subcutaneous fat can be transferred from the abdomen or, less commonly, the buttock to reconstruct an entire breast.

If the shape of the irradiated breast is acceptable but there is a volume difference between the two sides, another option is to adjust the normal breast. This can range from a simple breast lift to a breast reduction.

It is important to realise that the reconstructive options after breast conserving surgery are not limited to loco-regional flaps or lipofilling. For women with small breasts, those facing wide local excisions or for women considering risk-reducing surgery, a skin-sparing mastectomy with primary reconstruction may also be an option, providing no adjuvant radiotherapy is required. A recent study has shown that in selected cases (women with small tumors who are also good candidates for BCS) a skin-sparing mastectomy with primary autologous breast reconstruction achieved significantly better aesthetic results, in comparison to a similar group of patients undergoing pre-operative chemotherapy, breast conserving surgery and radiotherapy.

It is difficult to reach defects in the upper-medial quadrant of the breast with loco-regional flaps and this area is also hard to reconstruct when skin has been resected. If the defect is not suitable for lipofilling, one could consider a skin sparing mastectomy and primary autologous breast reconstruction, which also reduces the long-term oncological risks,

Timing of partial breast reconstruction

Unfortunately with breast conserving surgery, we have seen suboptimal aesthetic results following immediate flap reconstruction and radiotherapy. The other disadvantages of immediate partial autologous reconstruction include the risk of positive resection margins and the logistical difficulty of organising these cases in the days or weeks following a breast cancer diagnosis.

Every woman who undergoes immediate partial reconstruction with a loco-regional flap and encounters positive section margins, early recurrence or flap fibrosis due to the effects of radiotherapy, has already lost one reconstructive option. Once again, patient selection is the key.

We offer immediate partial reconstruction with glandular remodelling or breast reduction to patients with defects of less than 1/8 of the gland. For resections of greater than 3/8, a skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with either an implant or autologous tissue is indicated. Offering immediate reconstruction to patients with resections between 1/8 and 3/8 is debatable and we prefer to delay the final reconstruction until 6 months after the completion of radiotherapy. Meanwhile, the shape of the breast can be improved by re-draping of the remaining gland, filling the cavity with saline or a temporary implant, or just accepting the temporary deformity. Adopting this strategy preserves our reconstructive options and we have therefore not burnt any bridges.

Fig.2(a)

Fig.2(b)

Fig. 2(a) Breast conserving surgery in a large breast. | Fig. 2(b) Post-operative result after glandular remodelling of the right breast and conventional breast reduction of the left breast. |

References

Oncoplastic surgical techniques for personalized breast conserving surgery in breast cancer patient with small to moderate sized breast.

Yang JD, Lee JW, Kim WW, Jung JH, Park HY. J Breast Cancer. 2011 Dec;14(4):253-61.Oncoplastic breast surgery: a review and systematic approach.

Berry MG, Fitoussi AD, Curnier A, Couturaud B, Salmon RJ. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010 Aug;63(8):1233-43.MRI for breast conservation surgery.

Mann RM, Boetes C. Lancet. 2010 Jun 26;375(9733):2213.Oncological and aesthetic considerations of conservational surgery for multifocal/multicentric breast cancer.

Patani N, Carpenter R. Breast J. 2010 May-Jun;16(3):222-32. Review.The use of oncoplastic reduction techniques to reconstruct partial mastectomy defects in women with ductal carcinoma in situ.

Song HM, Styblo TM, Carlson GW, Losken A. Breast J. 2010 Mar-Apr;16(2):141-6. Epub 2009 Jan 19.Preserving life and conserving the breast.

Veronesi U, Zurrida S. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Jul;10(7):736.Assessment of immediate conservative breast surgery reconstruction: a classification system of defects revisited and an algorithm for selecting the appropriate technique.

Munhoz AM, Montag E, Arruda E, et al. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;121:716–27.Oncoplastic approaches to partial mastectomy: an overview of volume-displacement techniques.

Anderson BO, Masetti R, Silverstein MJ. Lancet Oncol. 2005 Mar;6(3):145-57.Better cosmetic results and comparable quality of life after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate autologous breast reconstruction compared to breast conservative treatment.

Cocquyt VF, Blondeel PN, Depypere HT, Van De Sijpe KA, Daems KK, Monstrey SJ, Van Belle SJ. Br J Plast Surg. 2003 Jul;56(5):462-70.Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer.

Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, Jeong JH, Wolmark N. N Engl J Med. 2002 Oct 17;347(16):1233-41.Integration of plastic surgery in the course of breast-conserving surgery for cancer to improve cosmetic results and radicality of tumor excision.

Petit JY, Rietjens M, Garusi C, Greuze M, Perry C. Recent Results Cancer Res 1998;152:202–11.Breast conservation is a safe method in patients with small cancer of the breast. Long-term results of three randomised trials on 1,973 patients.

Veronesi U, Salvadori B, Luini A, Greco M, Saccozzi R, del Vecchio M, Mariani L, Zurrida S, Rilke F. Eur J Cancer. 1995 Sep;31A(10):1574-9.

Techniques in breast conserving surgery

1. The ‘pedicled’ Latissimus Dorsi musculocutaneous Flap (LD flap)

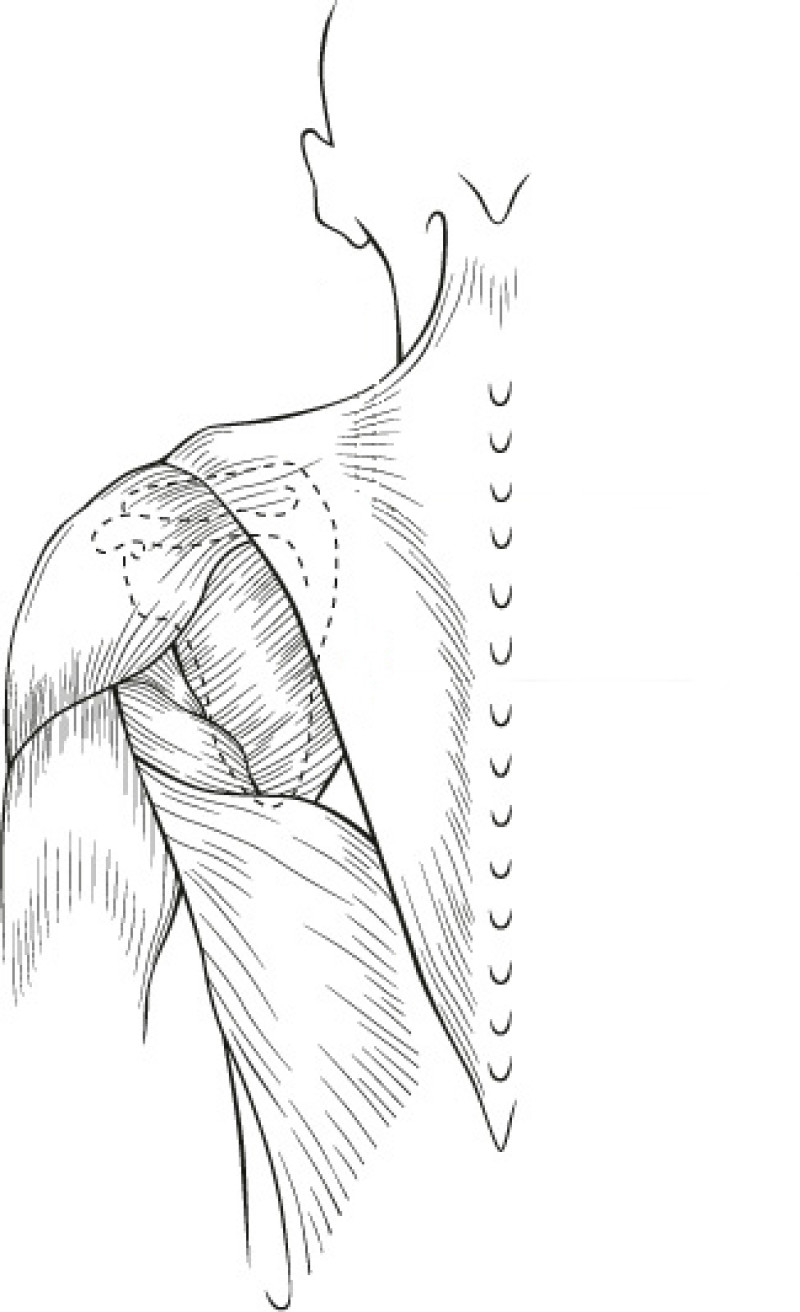

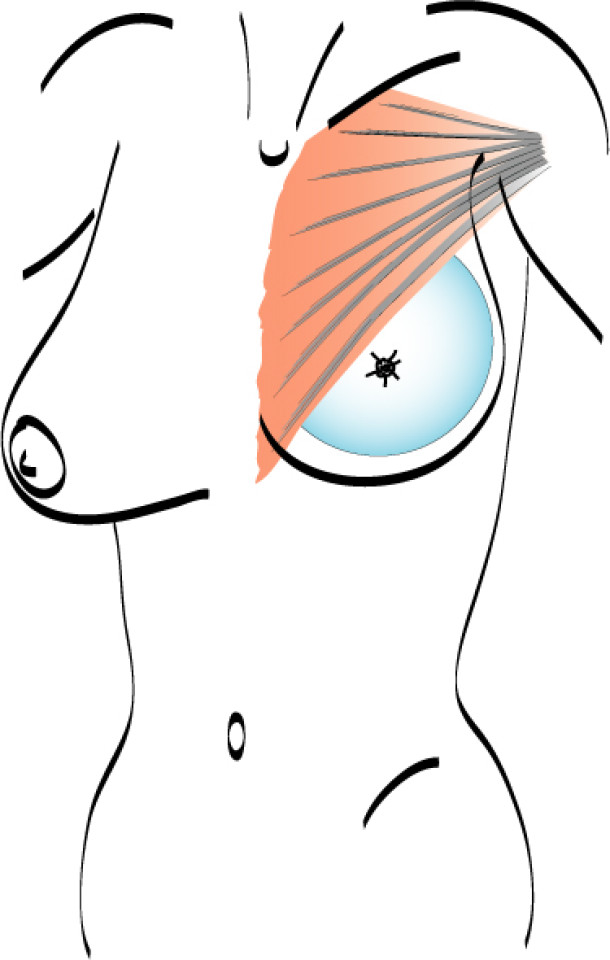

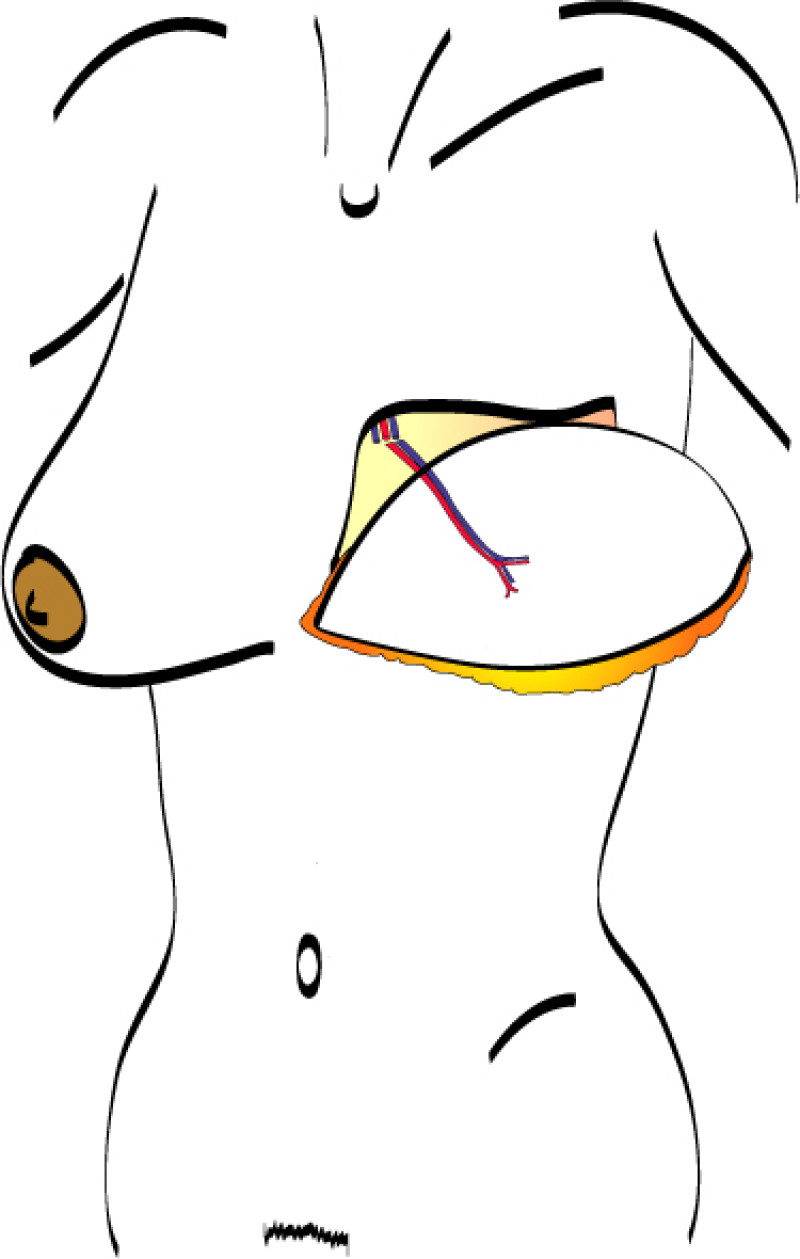

The Latissimus Dorsi (LD) flap was first described for autologous breast reconstruction in 1977. It consists of part or all of the largest muscle of the back, the latissimus dorsi muscle (fig. 1) together with an island of overlying skin and fat, which can be designed in a variety of shapes and directions (Fig.2a). Through a tunnel underneath the armpit, the flap can be transferred onto the breast or chest wall (fig. 2b). The blood vessels supplying the muscle and overlying skin, originate at the top of the axilla and are called the thoracodorsal artery and vein. These vessels are not divided during surgery and the tissue remains attached at all times. This flap is therefore described as ‘pedicled’, as no microsurgery is required. It is a relatively safe and simple procedure, with satisfactory cosmetic results.

Fig. 1(a)

Fig. 1(b)

Fig. 1(a): the muscles of the back | Fig. 1(b): The Latissimus Dorsi (LD) muscle, the largest and strongest muscle of the back |

Fig. 2(a)

Fig. 2(b)

Fig. 2: The Latissimus Dorsi (LD) flap is supplied by large nourishing blood vessels from the arm pit and can be transferred onto the breast or chest, with an island of overlying skin and fat. |

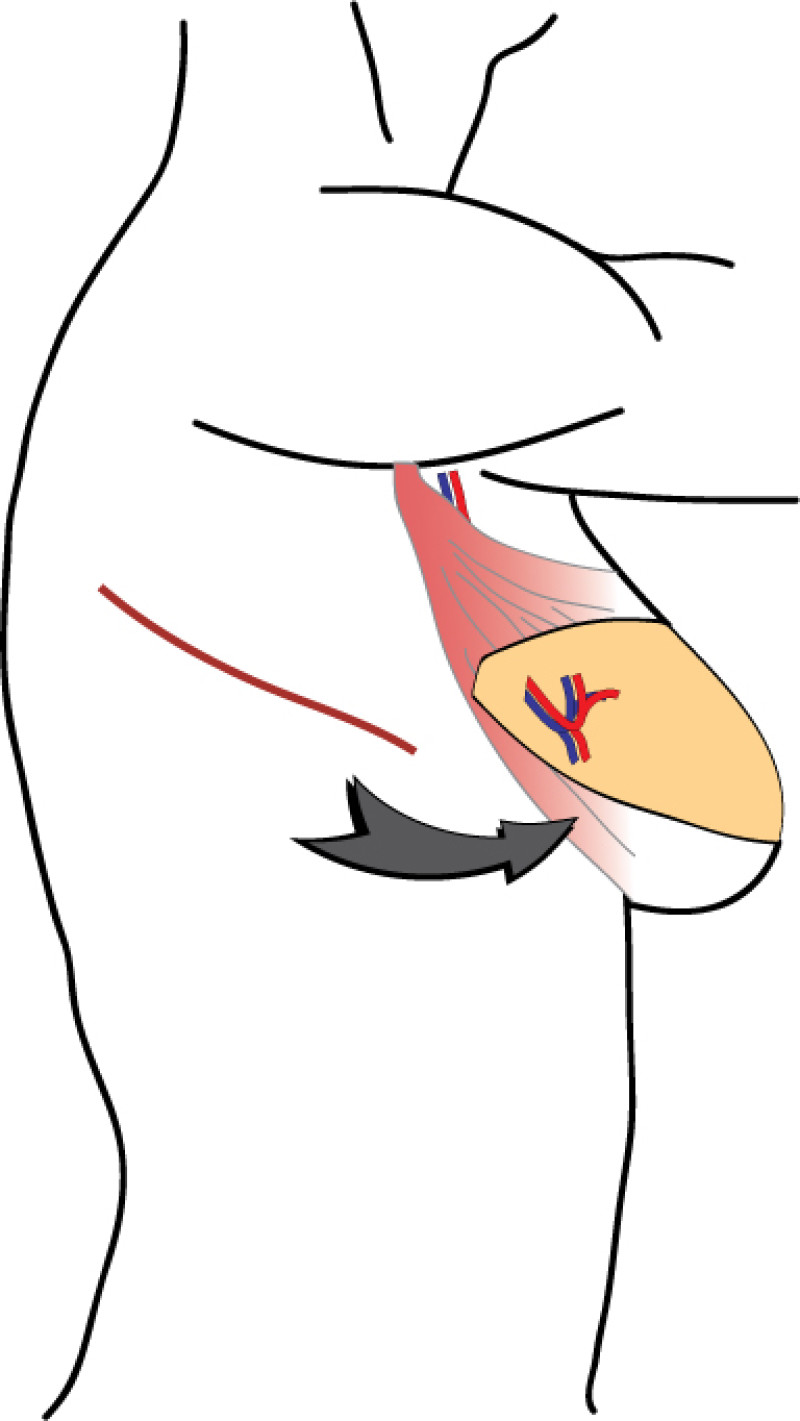

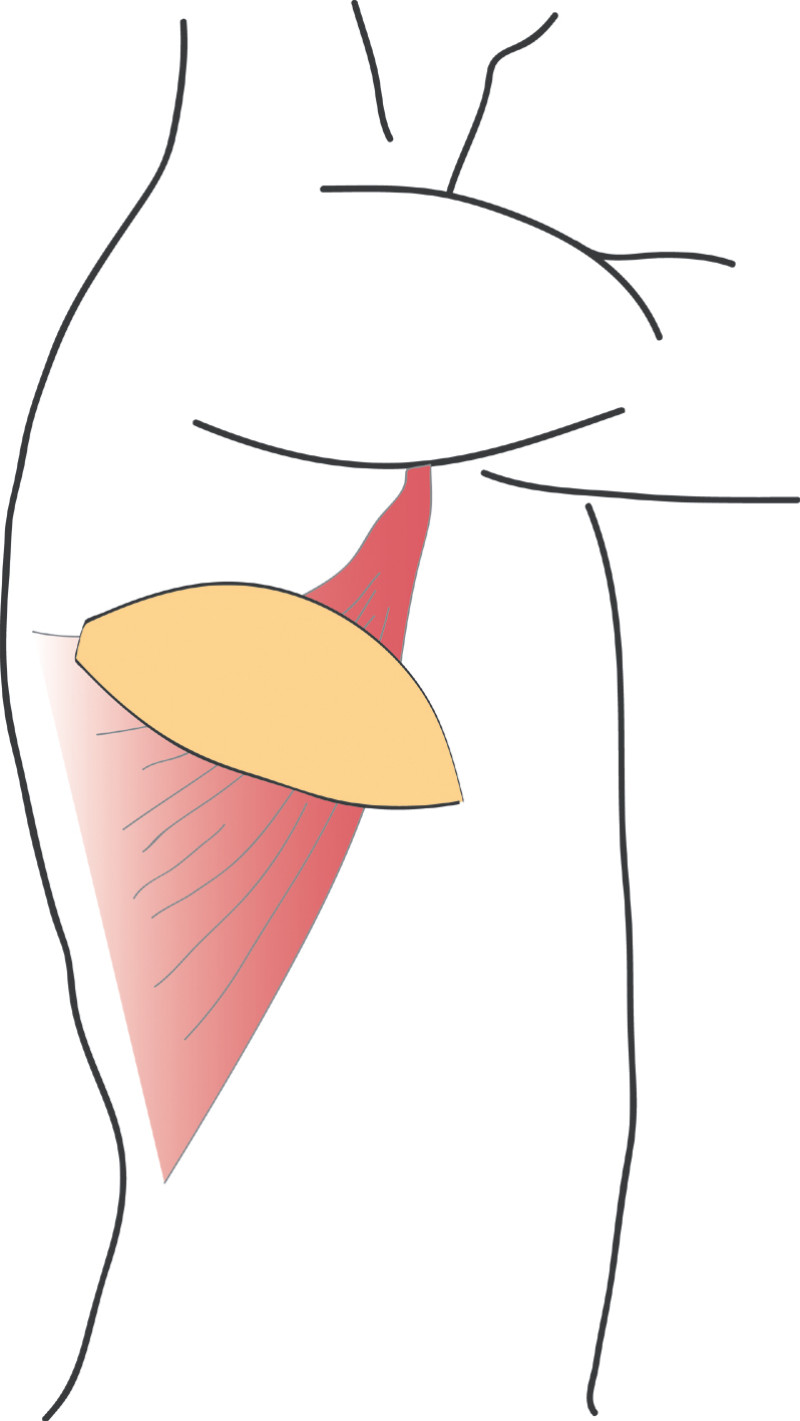

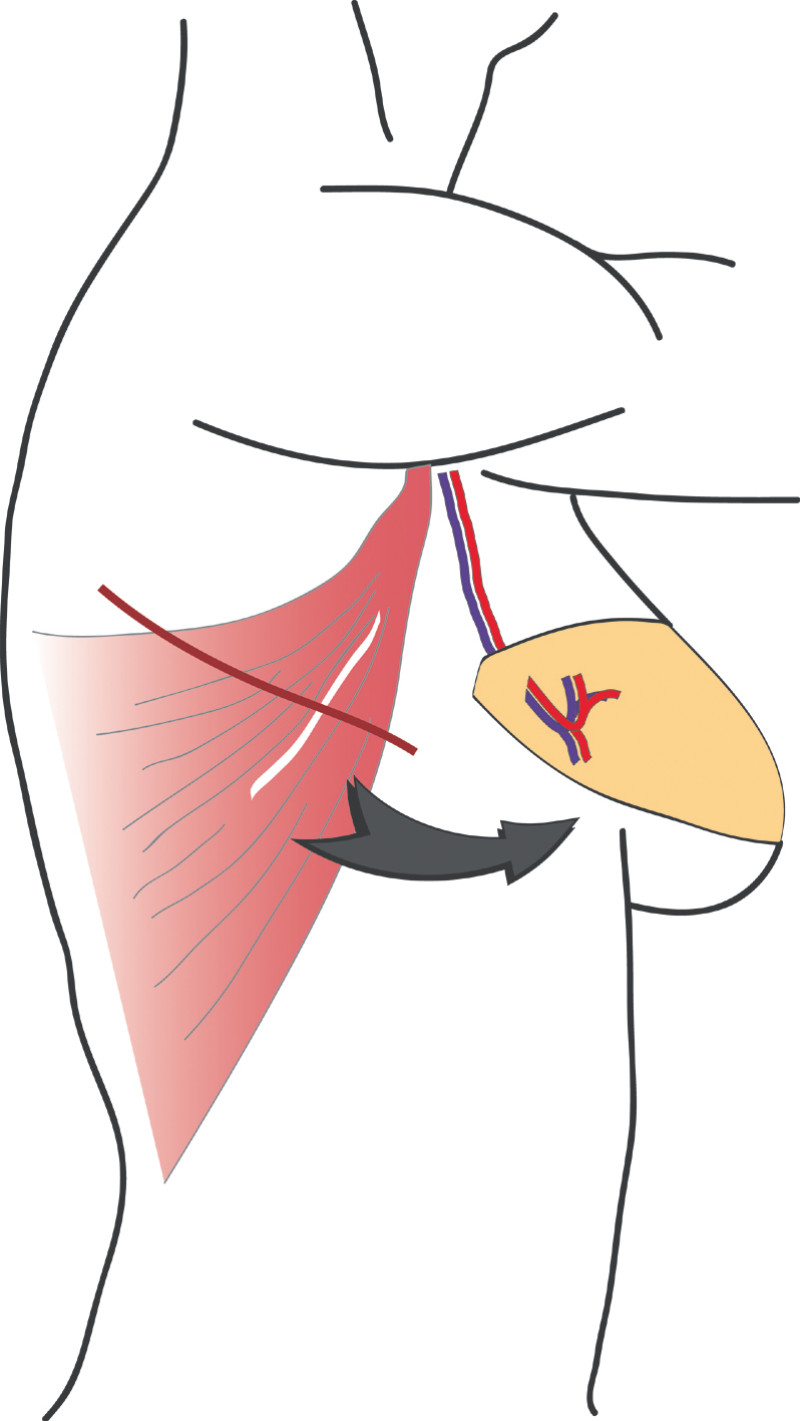

2. The ‘pedicled’ ThoracoDorsal Artery Perforator Flap (TDAP flap)

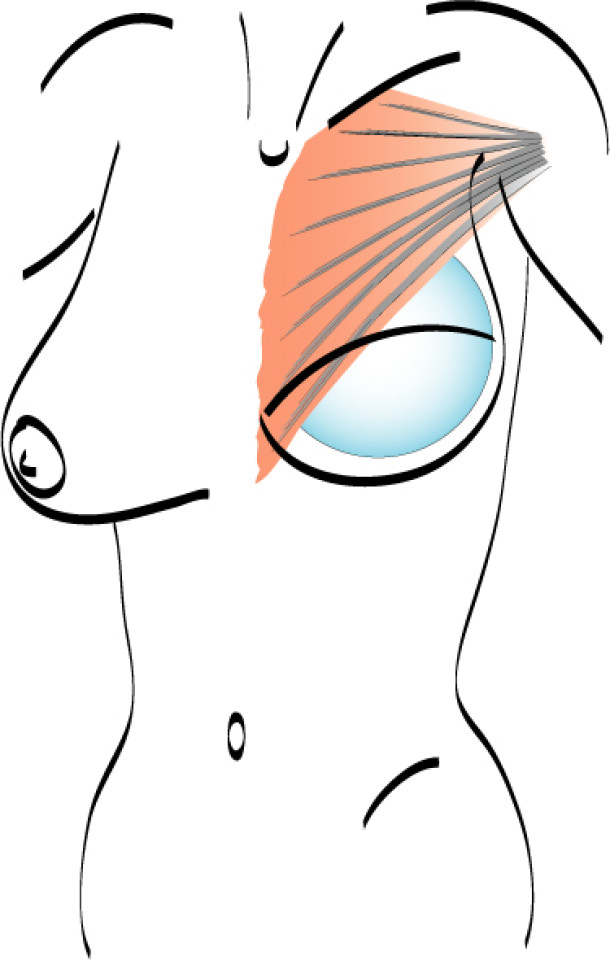

This flap is very similar to the LD flap, the main difference being that the latissimus dorsi muscle is separated in the line of its fibres to find the perforating (feeding) blood vessels. No muscle or major nerves are sacrificed. The latissimus dorsi remains in its original position and only the island of skin and fat is transferred. This is known as the ThoracoDorsal Artery Perforator (TDAP) flap) (Fig.3) and the latissimus dorsi muscle function is completely preserved.

Fig. 3(a)

Fig. 3(b)

Fig. 3(c)

Fig. 3: The ThoracoDorsal Artery Perforator (TDAP) flap: the latissimus dorsi fibres are separated during surgery but the muscle itself is left in place. Only an island of skin and fat from the back are transferred, together with the perforating (feeding) blood vessels. |

Both of these techniques allow reconstruction of quite substantial breast defects, especially in the central and outer breast quadrants. Removing part or all of the latissimus dorsi muscle can affect shoulder function in physically active people, whereas this is completely preserved by a TDAP flap. The transfer of the TDAP flap onto the breast is unfortunately limited by the length of the blood vessels that supply it from the axilla, so it can only be used for reconstruction of quite laterally placed defects. Reconstruction of an entire breast using these flaps usually necessitates the addition of an implant to achieve sufficient volume.

The main advantage of transferring tissue from the back in breast reconstruction is that the operation is less complex in comparison to microsurgical free tissue transfer. The disadvantages include an insufficient amount of tissue for complete breast reconstruction and the possibility of an unsatisfactory donor site scar. If a large amount of skin and fat are transferred, the contour of the back may be affected, leading to asymmetry. The color and texture of the skin from the back is also different from the breast. Finally, sensation cannot be restored and involuntary contraction of the transferred muscle may sometimes be problematic.

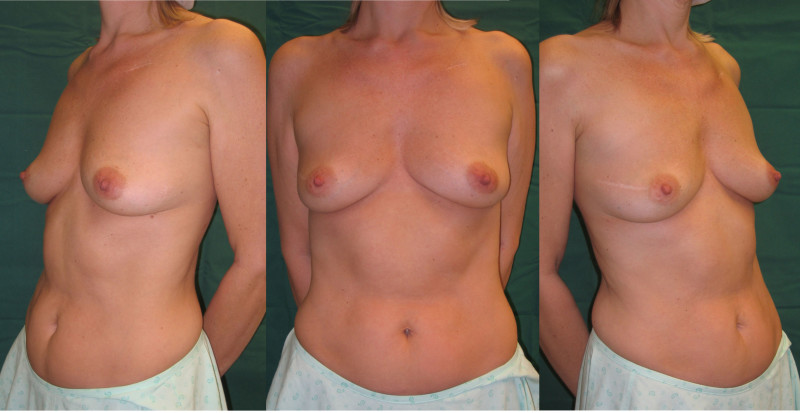

Fig. 4(a)

Fig. 4(b)

Fig. 4(c)

fig. 4(d)

Fig. 4(e)

Fig. 4 Pre-operative (a) and 3 year Post-operative pictures (d, e) of a patient who underwent an upper-outer quadrantectomy of her right breast (b), combined with an immediate pedicled TDAP flap (c).A small skin island can be seen in the anterior axillary fold, allowing flap evaluation and monitoring after surgery. |

The main indications for the LD or TDAP flap are:

to restore the anterior axillary fold

to fill defects in the outer quadrants of the breast

to cover exposed implants

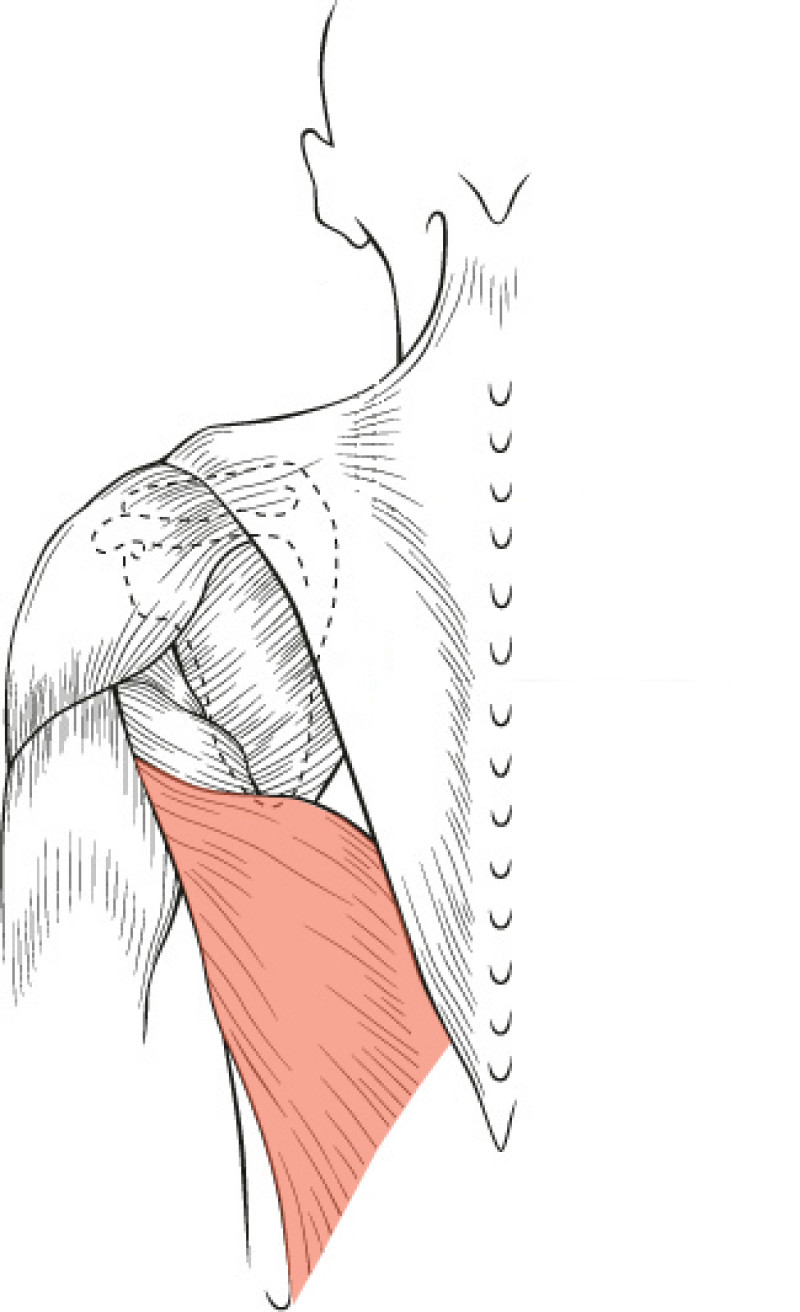

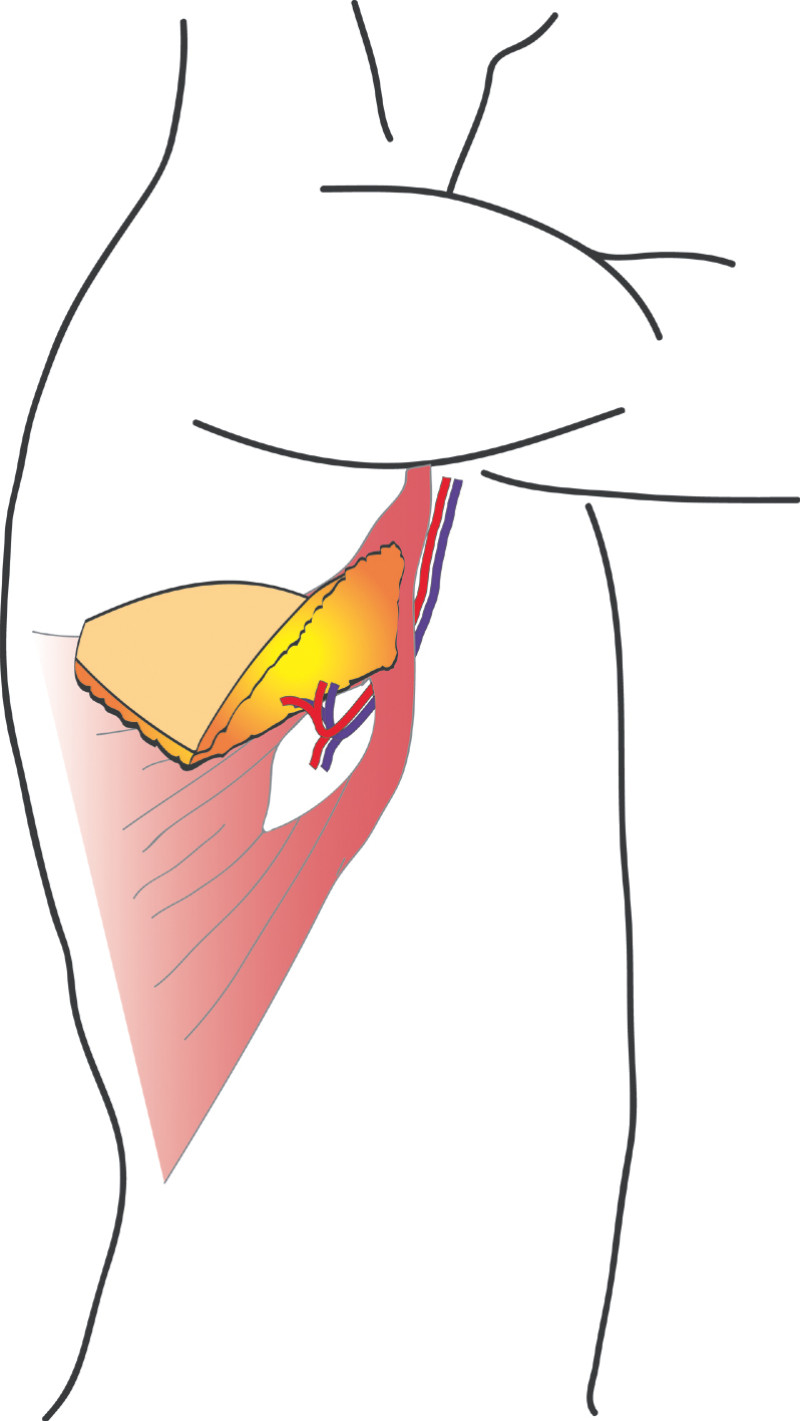

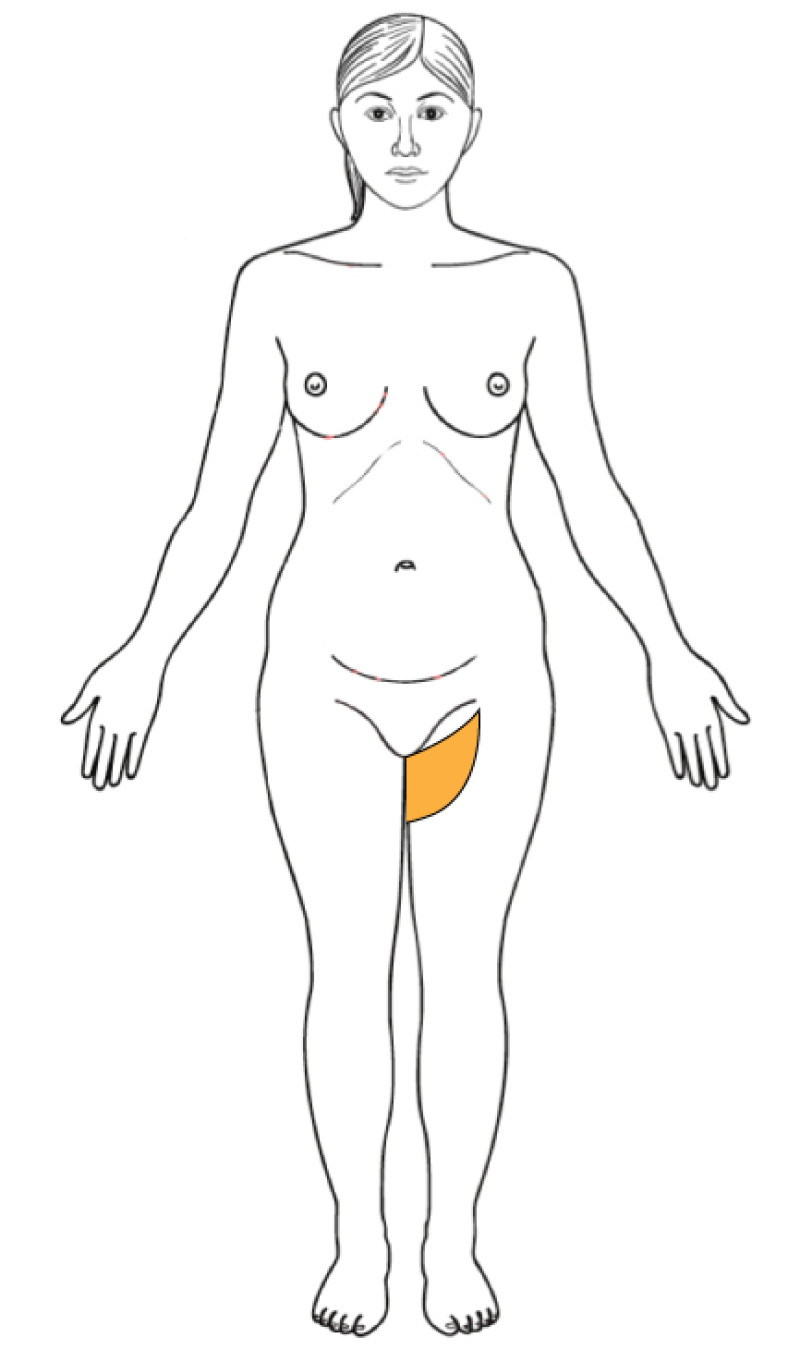

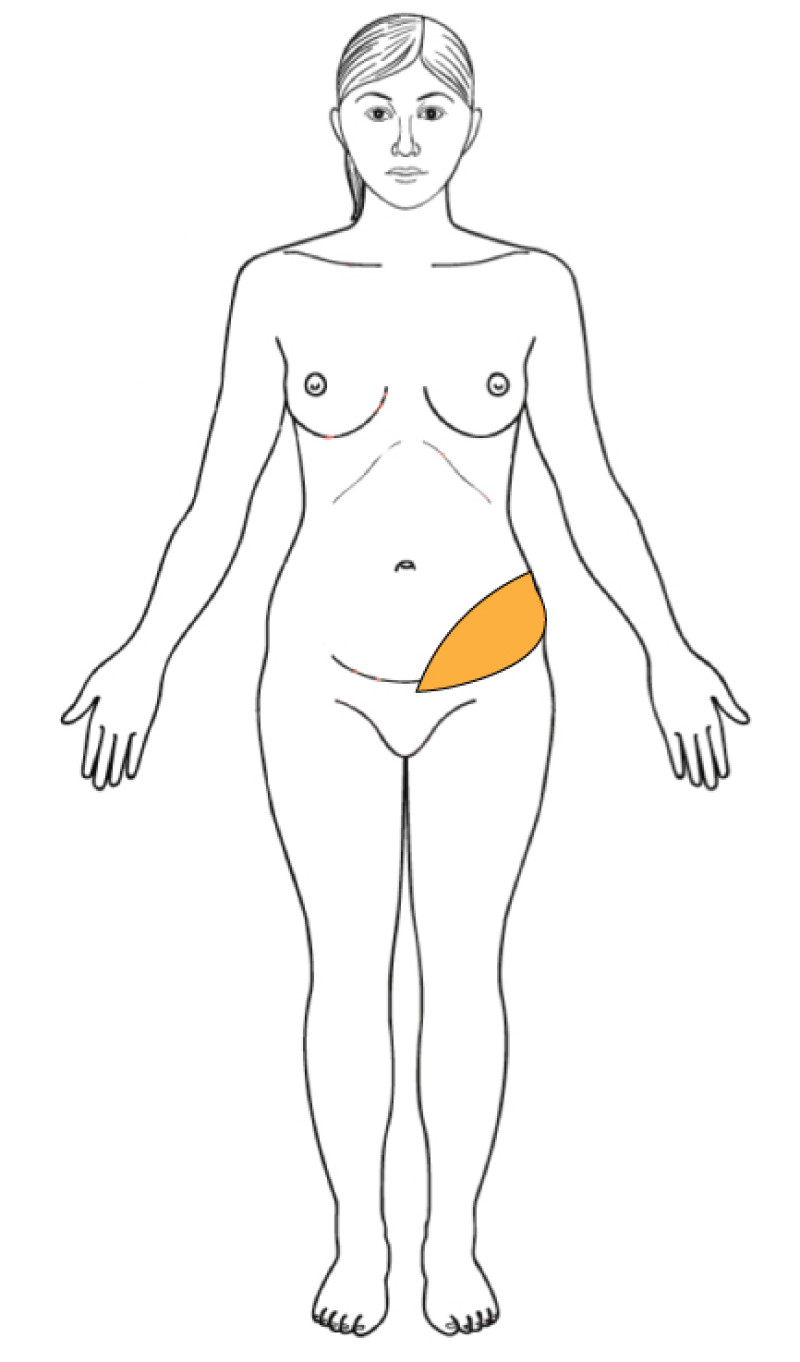

3. Breast conserving surgery - tissues flank (LICAP)

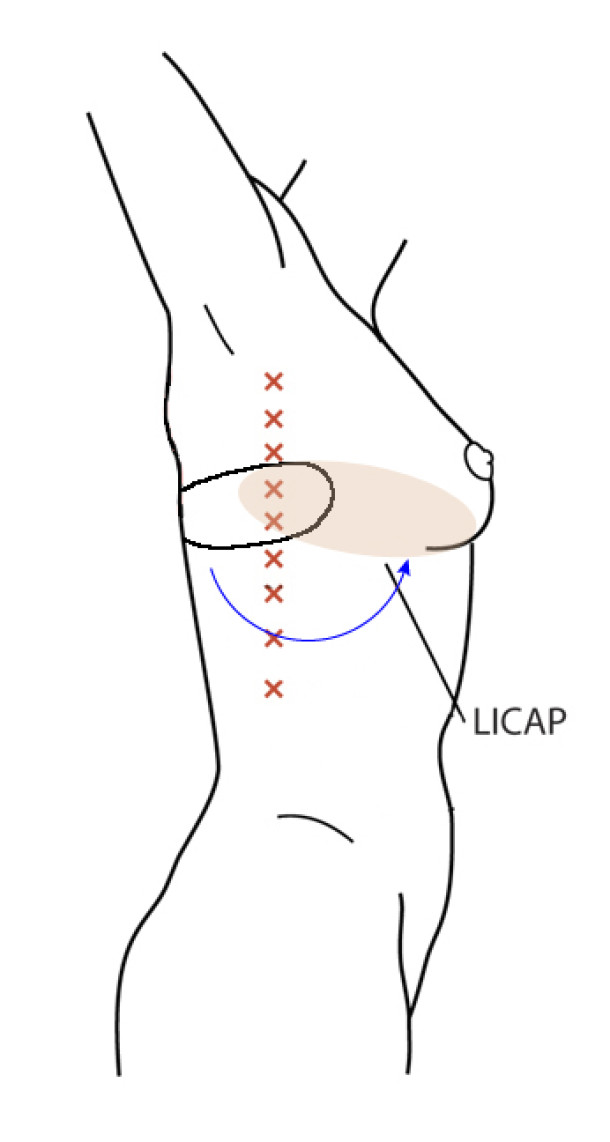

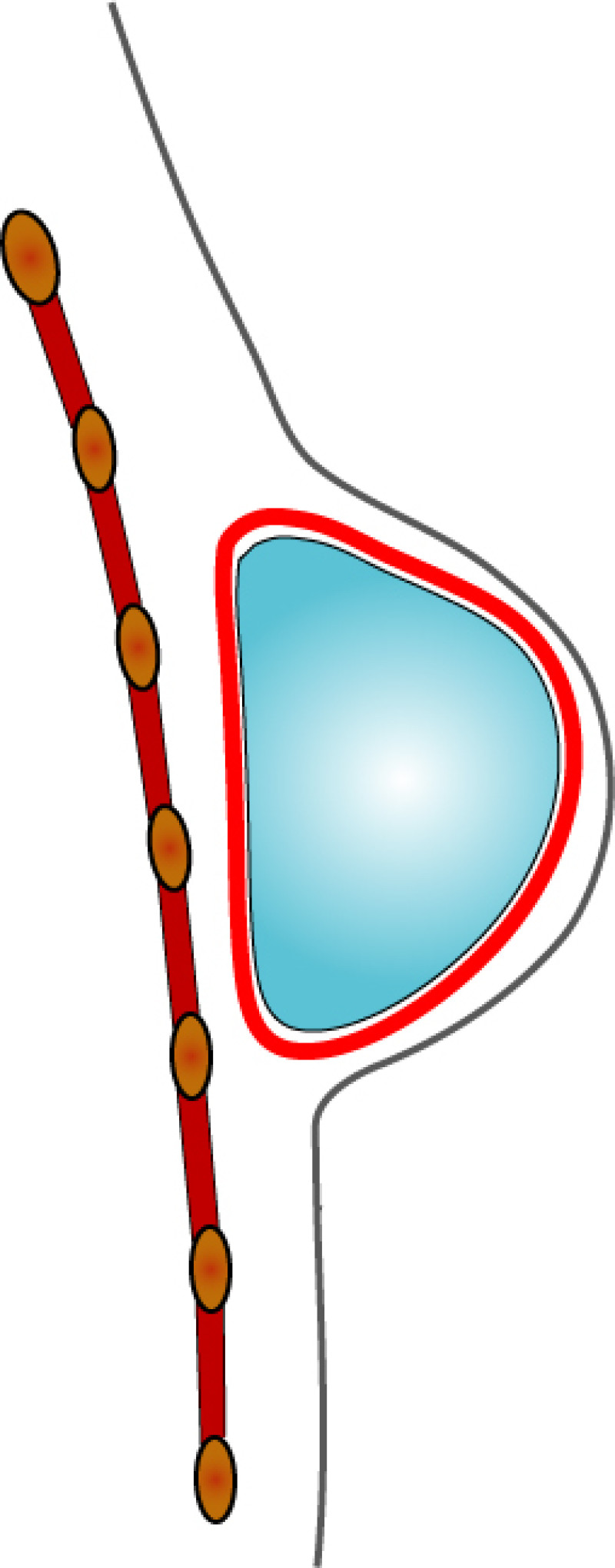

Occasionally, redundant tissue is present close to the breast, on the flank. This tissue, consisting of the skin and underlying fat, is supplied by blood vessels called intercostal perforators (Fig.5). Similar to to the ThoracoDorsal Artery Perforator (TDAP) flap, an elliptical skin island can be harvested on these small vessels, known as the Lateral Intercostal Artery Perforator (LICAP) flap. This tissue can then be rotated into an adjacent breast defect, using its vessels as a pivot point, without the need for microsurgery.

The LICAP flap leaves a horizontal scar on the flank and back. This scar can be completely hidden underneath the bra and arm and is often inconspicuous. The LICAP flap has similar advantages and disadvantages to the TDAP flap. However, only patients with tissue available on their flanks are going to be suitable for this technique and only minor defects on the lower, lateral part of the breast can be filled.

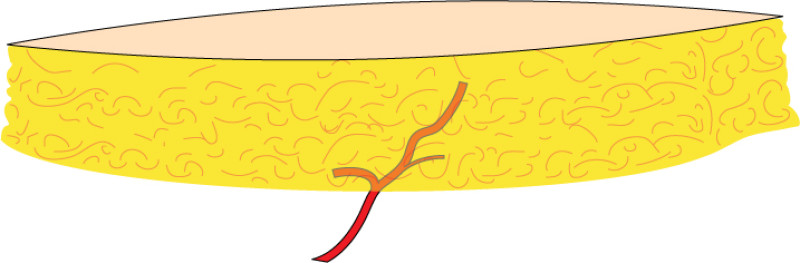

Fig. 5: The LICAP flap: the lateral intercostal perforators lie on a line in the axilla (red crosses). Based on one or two of these vessels, an island of skin and fat from the flank and/or back can be raised. The flap is then rotated through 180 °, pivoting on these arteries, to reach the breast defect.

Fig. 6(a)

Fig. 6(b)

Fig. 6(c)

Fig. 6: (a) Pre-operative picture of a right breast with a depression and lack of volume. (b,c) Post-operative picture after transferring the LICAP flap from the right flank. The shape and volume of the breast are restored, leaving a horizontal scar within the bra-line. |

IV. Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy

Introduction

In many patients mastectomy is still indicated. Factors influencing this decision are the size of the primary tumor, unfavorable localization of the tumor, multifocality or multicentricity of the cancer and finally recurrence after previous breast conserving surgery. Fortunately we have moved away from the conventional radical mastectomy and in most cases a modified radical mastectomy or skin sparing mastectomy is offered. Depending on the wishes of the patient and the size and shape of the breast, skin-sparing mastectomies can be combined with either reduction of the skin envelope or breast lift.

Replacement of the breast volume and regaining the shape of a natural breast may be achieved by using either implants or transferring autologous (body-own) tissue from the abdomen, buttocks, thighs or back.

When a primary reconstruction is envisioned the inframammary crease, the pectoral muscle and the overlying skin should all be preserved during the mastectomy procedure. In case of shortage of breast skin the envelope needs to be replaced either by skin from the free flap or by a period of preoperative expansion in case of implant reconstruction.

When confronted with a secondary or tertiary breast reconstruction, the degree of surgical post-ablative damage and radiotherapy damage to the different anatomical structures of the breast needs to be assessed. More aggressive ablative surgery, higher doses of radiotherapy (or higher sensitivity to radiotherapy), the number and type of previous reconstructive attempts and the absence of the nipple-areolar complex will all make the reconstructive procedure more complex and negatively influence the final result.

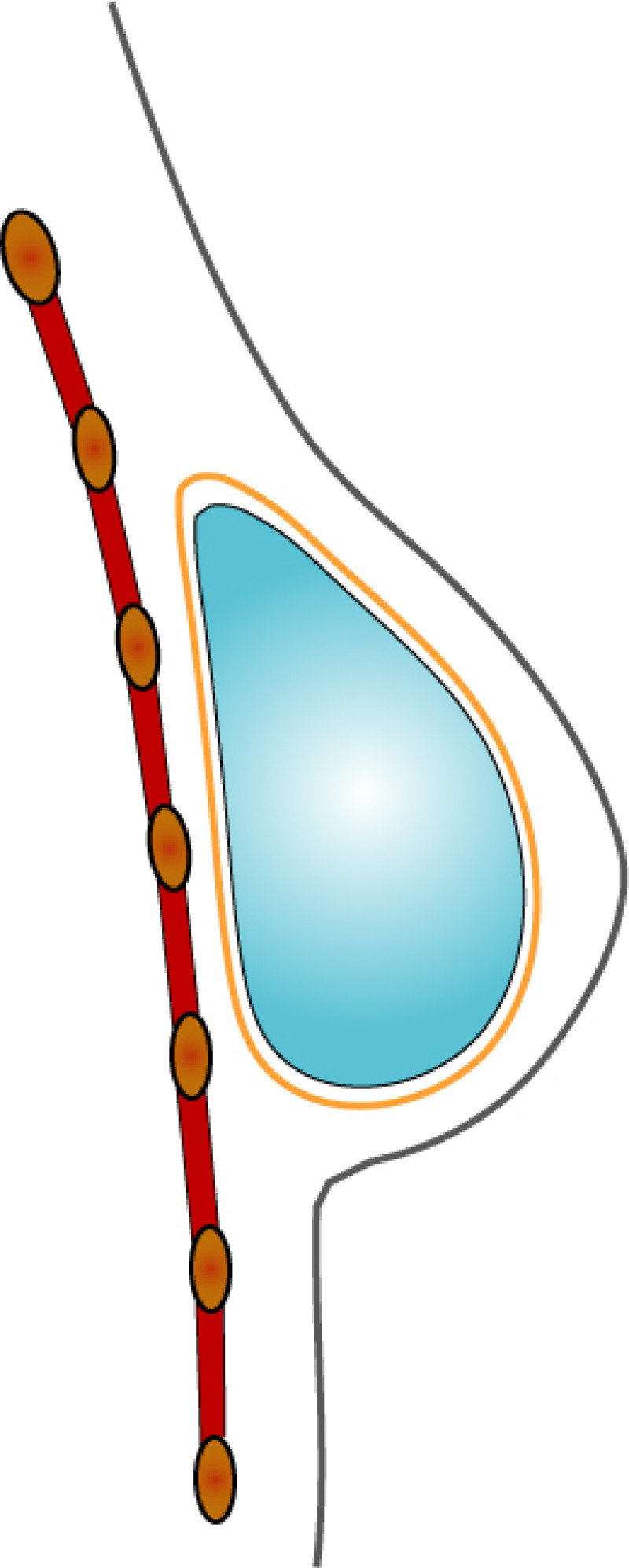

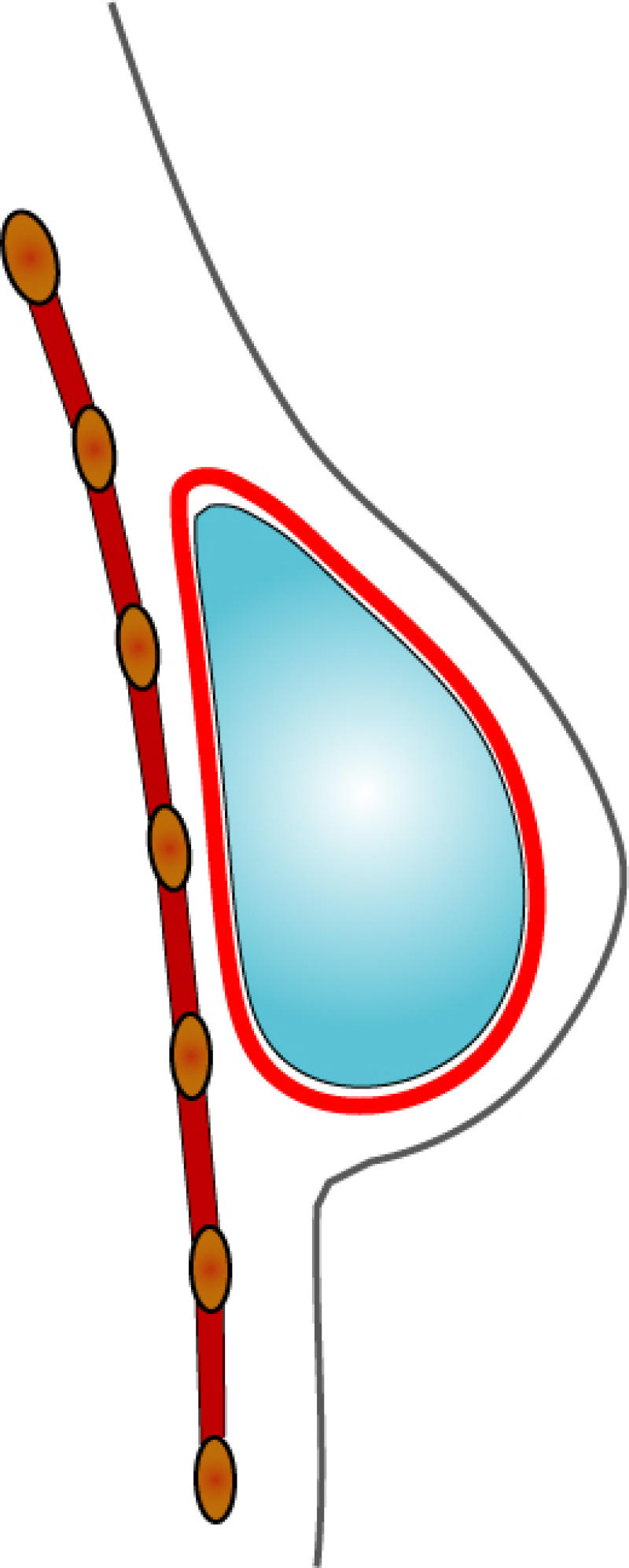

V. Implants

Implants are essentially balloons mimicking the shape of a breast that can be placed underneath the skin or muscle of the chest wall (pectoral muscle). The outer layer of the balloon is usually made of silicone and the implant is filled with either silicone gel or a saline solution.

Timing

In an immediate implant reconstruction, the scar can be confined to the location of the areola, the implant placed through this access incision and the skin closed (Fig. 1). Later, using the same incision, a nipple reconstruction can be performed, limiting scarring.

Fig. 1: an immediate implant reconstruction performed by a central areolar incision only. The implant is placed in a pocket underneath the pectoral muscle

In a delayed implant reconstruction, the horizontal or diagonal mastectomy scar is already present and can be used to introduce the implant. Unfortunately though, the longer mastectomy scar remains visible (fig. 2). A delayed implant reconstruction can be done in one stage if there is sufficient overlying skin or if the breast is relatively small. In these instances, the prosthesis is immediately placed beneath the pectoralis major muscle. Usually, however, the reconstruction is performed in two stages.

Fig. 2: a delayed implant reconstruction after a modified radical mastectomy. The remaining skin needs to be expanded first and the expander replaced by a permanent sub-pectoral implant at a second procedure.

At the first operation, an expander is placed underneath the skin and muscle of the chest wall to stretch and create a pocket for the final prosthesis. An expander is an implant that is connected to a small subcutaneous valve, welded in the expander or placed at a distance and connected by a thin tube that can be punctured and filled with saline. This mechanism allows a gradual increase or decrease in the volume of the expander. In general, the purpose of an expander is to stretch the overlying skin near the chest wall and prepare it for a permanent prosthesis. The inflation begins approximately two to three weeks after the first operation. Every two weeks, the expander is filled, until it matches the size and volume of the other breast. Sometimes over-expansion is required to obtain a more natural breast shape. At the second procedure, the expander is removed and a permanent prosthesis inserted (Fig. 2).

A permanent expander can also be used. The procedure is the same as for a temporary expander but the device will not be replaced with a permanent prosthesis. This saves one operation but does not offer an opportunity for adjustment if the breast shape is less than ideal.

Implant types

Implants have dramatically improved over the last decade. The wall of the prosthesis used for reconstruction is now rough, so that it is less likely for an implant to move after surgery. Additionally, the devices are made in the shape of a pear or tear drop to mimic the shape of a natural breast. Instead of the traditional silicone gel, a cohesive gel is now used: if the shell of the prosthesis tears or breaks this gel will not spread elsewhere (Fig. 3), making the implants much safer.

Fig. 3: Most modern prostheses have a tear drop shape and are filled with a cohesive silicone gel.

Advantages of implant reconstruction

Implant based breast reconstruction is a relatively short, simple procedure with a low risk of postoperative complications; no additional scars are left on the body and the volume of the implants may be adjusted to the patient’s wishes, if expanders are used.

Disadvantages of implant reconstruction

The main drawback of implant based reconstruction is the high risk of late complications. Implants, like any medical device, are subject to wear and tear and eventually failure over time. The longer the prosthesis remains in situ, the higher this risk. Complications lead to further operations and ultimately a greater financial cost, when compared to autologous reconstruction.

Possible complications

1. Early complications

As with any surgical operation, bleeding, infection and wound healing problems are all possible. There is a slightly increased risk of infection with implants, as they are made of foreign material. Fluid collections around the implant, called seromas, can also often be detected following surgery.

2. Late complications

capsule formation and capsular contracture: capsular contracture is the most frequent late complication of implant based reconstruction and presents with firmness and deformation of the breast, with or without pain. Over time, the scar tissue surrounding an implant, which is soft and pliable in the beginning, may thicken and harden. As a general principle, the longer the implant remains in place, the higher the chances of this developing. A study by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) in the United States has shown that the implants themselves are not responsible for any disease or illness but that repeated operations are the main cause of problems. As a result of this increased number of procedures, the total cost of implant based reconstruction is higher than autologous reconstruction. An implant reconstruction is estimated to last for 7 to 10 years.

wrinkling and rippling of the overlying skin

palpable implant edges

chronic pain

displacement or rotation of the implant

infections

leak, tear or rupture of the implant, caused by either trauma or material fatigue

necrosis of the overlying skin

siliconomas: these are less common now as the silicone gel is cohesive

There is however, no link between breast implants and auto-immune diseases, cancer, breast cancer recurrence, dermatological conditions or degenerative diseases.

In our experience and also according to the medical literature, administering radiotherapy, either before or after placing a breast implant, leads to a significant increase in all of these complications. In addition, later complications will develop earlier. The effects of radiotherapy can last for up to 15-20 years and as a result, many reconstructive centers no longer use implants in combination with radiotherapy.

Patients must also realize that it is frequently not possible to obtain the same excellent aesthetic results that can be achieved with autologous reconstruction, using implant based breast reconstruction.

Indications

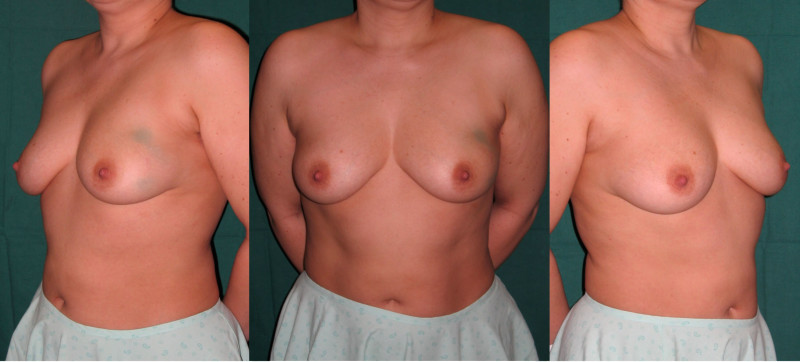

Ideal candidates for implant based breast reconstruction are non-irradiated women with small non-sagging breasts. Good results can be achieved, particularly in bilateral reconstructions (fig. 4, 5). Patients who do not want additional scars elsewhere on their body or women with other associated medical problems that preclude a long surgical procedure (heart disease, coagulopathies, short life expectancy) are also potentially good candidates.

It is important to realise that implant reconstruction is not possible in patients in whom the entire pectoral muscle has been removed, the mastectomy skin flaps damaged or when severe radiation changes are present.

Fig. 4(a)

Fig. 4(b)

Fig. 4(c)

Fig. 4(d)

Fig. 4(e)

Fig. 4(f)

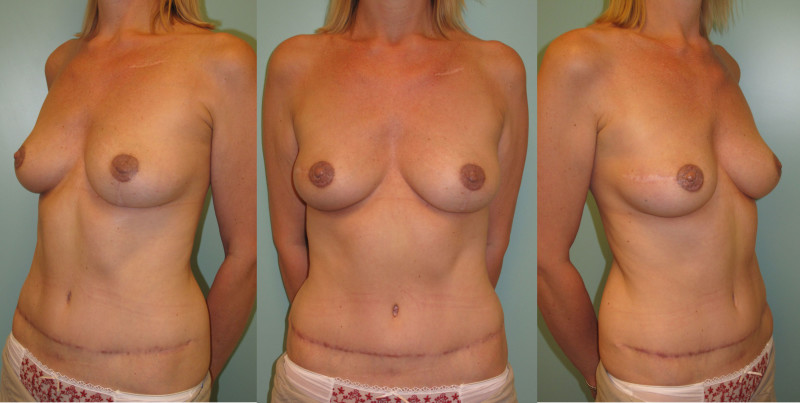

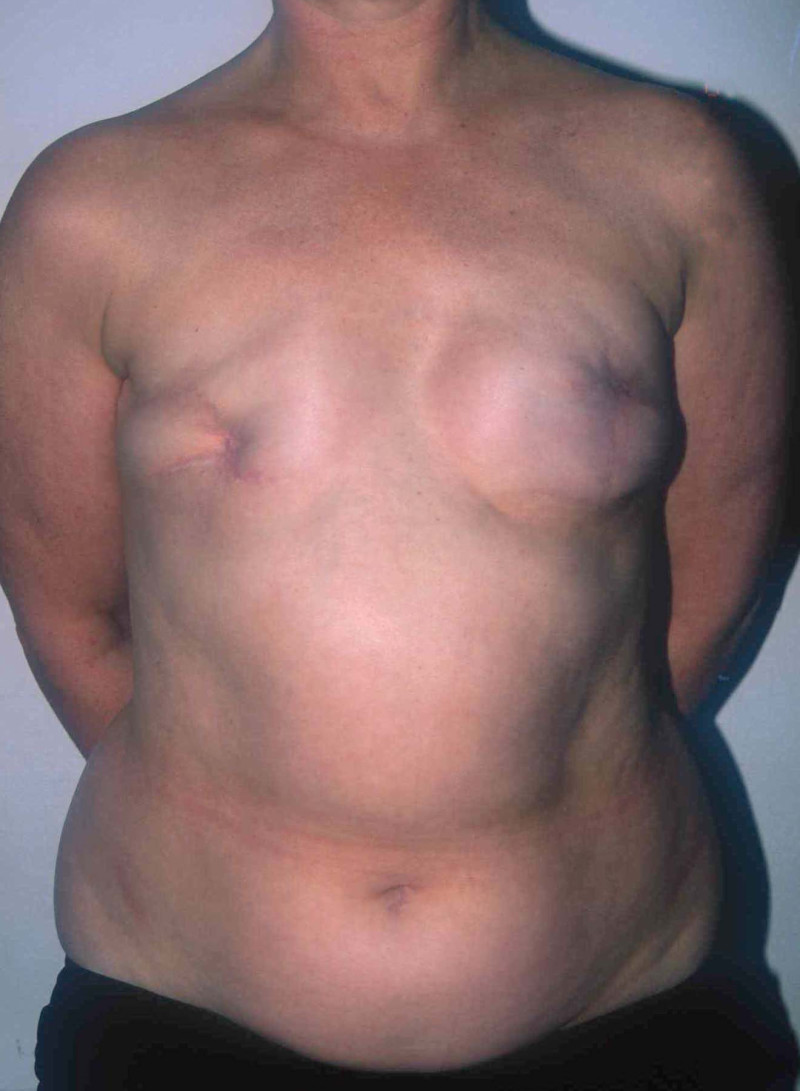

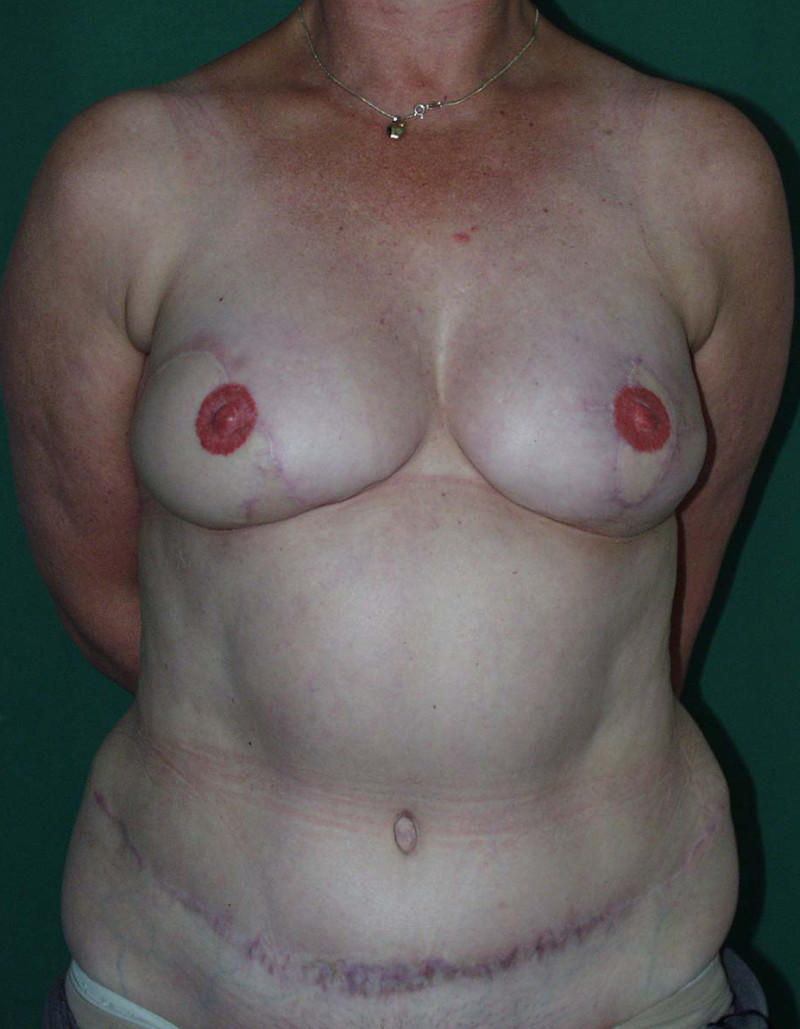

Fig. 4: Pre-operative (a) and postoperative pictures of the same patient who underwent bilateral skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction using expanders (b) and later exchange for permanent breast prostheses (c, d). The tattooing of the nipple reconstruction is initially dark but the color fades with time. (e) seven years and (f) nine years after the reconstruction,following rupture of the saline-filled right breast prosthesis. |

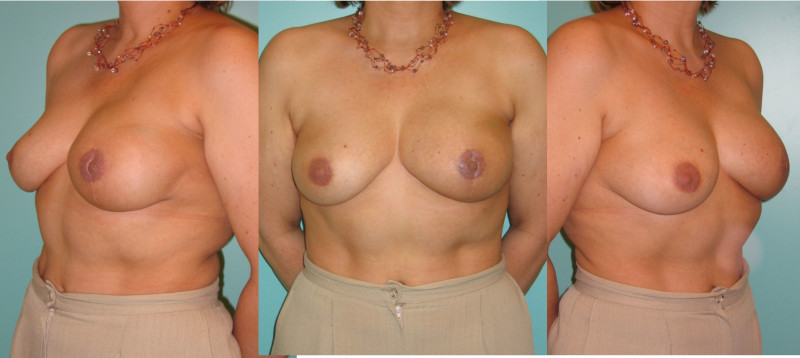

Fig. 5(a)

Fig. 5(b)

Fig. 5: Pre-operative (a) and postoperative (b) pictures of a bilateral immediate implant breast reconstruction after areola-sparing mastectomies. |

Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline: Breast Reconstruction with Expanders and Implants

Read about breast reconstruction guidelines with implants in the following documents. These reports have been put together by a special guideline committee of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), using only data from sources and publications with a high degree of evidence based medicine (EBM). Breast reconstruction guidelines for autologous tissue will be available by the end of 2014.

Full versions:

References

Cronin TD, Gerow FJ. Augmentation mammaplasty: a new “natural feel” prosthesis. Transactions of the Third International Congress of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Oct 13–18, 1963, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Excerpta Medica Foundation, pp 41–49.

Cronin TD. Subcutaneuos mastectomy and gel implants. AORNJ. 1969;10:81-85.

Cronin TD, Upton J, McDonough JM. Reconstruction of the breast after mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:1-14.

Radovan C. Tissue expansion in soft-tissue reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:482-492.

Deapen DM, Pike MC, Casagrande JT, et al. The relationship between breast cancer and augmentation mammaplasty: An epidemiologic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:361.

Sanchez-Guerrero J, Coldiz GA, Karlson EW, et al. Silicone breast implants and the risk of connective-tissue disease and symptoms. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1666-70.

Spear SL, Onyewu C. Staged breast reconstruction with saline-filled implants in the irradiated breast: recent trends and therapeutic implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(3):930-42.

Spear SL, Clack C, Howard MA. Postmastectomy reconstruction of the previously augmented breast: diagnosis, staging, methodology, and outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg.2001;107:1167.

Nahabedian MY, Tsangaris T, Moben B, et al. Infectious complication flowwing breast reconstruction with expanders and implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:467.

Salgarello M, Visconti G, Barone-Adesi L. Nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate implant reconstruction: cosmetic outcomes and technical refinements. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(5):1460-71.

Jansen LA, Macadam SA. The use of AlloDerm in postmastectomy alloplastic breast reconstruction: part II. A cost analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(6):2245-54.

Jansen LA, Macadam SA. The use of AlloDerm in postmastectomy alloplastic breast reconstruction: part I. A systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(6):2232-44.

VI. Lipofilling

What is lipofilling

Introduction

Lipofilling (fat transfer or structural fat grafting) is now an established technique. It uses patients’ own fat as a permanent filler to add volume to soft tissues. The fat is harvested with thin cannulas, through small incisions, using conventional liposuction. After filtering, the isolated fat cells are then injected into the deficient area(s). In addition to adding volume, lipofilling reduces scarring, improving the quality and elasticity of the overlying skin. It’s mechanism of action is not fully understood but by repeated clinical application, this technique has demonstrated its safety and efficacy.

Lipofilling is used in soft tissue augmentation, body contouring, facial rejuvenation, facial reconstruction (e.g. Romberg’s disease) and breast surgery (both reconstructive and aesthetic).

Technique

Preoperatively, suitable donor site areas for fat harvesting are identified. These include the inner aspect of the knee, the thigh, the buttock, abdomen, love handles, back, upper inner arm and neck. The donor and recipient areas are photographed to compare pre- and postoperative results.

Lipofilling can be performed under either local or general anaesthesia. Local anaesthesia is only used when small volumes of fat are required. The donor site is always infiltrated with a mixture of local anesthesia and adrenaline to reduce post-operative discomfort and bruising.

Fig. 1(a)

Fig. 1(b)

Fig. 1(c)

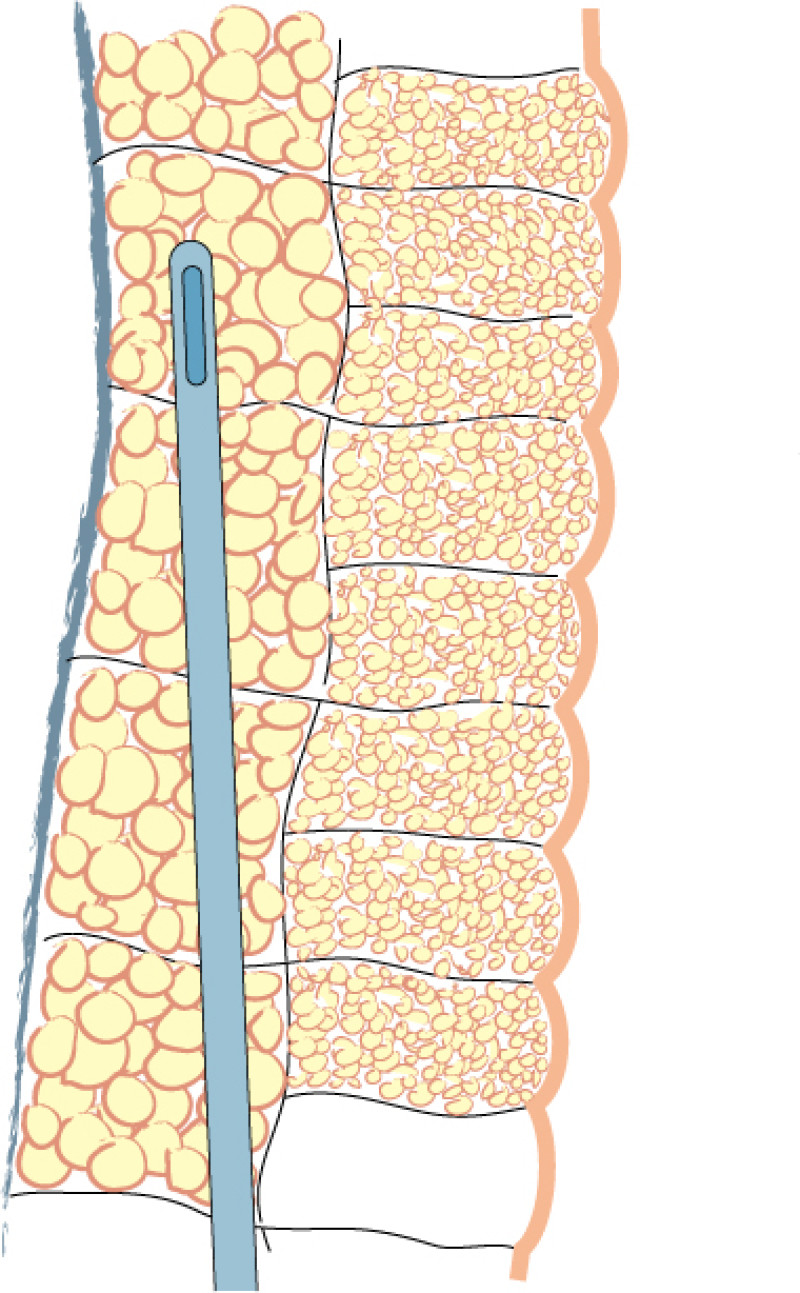

Fig. 1: Liposuction of the subcutaneous fat is performed using a 3mm. cannula in the deepest layer (a), a 2 to 3 mm. cannula in the intermediate layer (b) and a 2 mm. cannula in the most superficial layer (c). |

Lipofilling takes between 45 minutes and 3 hours, depending on the volume of fat to be transferred. The fat is harvested through 5mm incisions placed within skin creases, such as the lower buttock fold or areas that are commonly hidden by underwear. Two to 3mm cannulas are used, but the more superficial the harvest, the thinner the cannula (fig. 1). The fat is aspirated at either high or low negative pressure, depending on the indication and the surgeon’s preference.

Fig. 2: The aspiration cannula connected to the “fat trap”. This collecting canister is connected by a tube to a negative pressure device or liposuction machine (seen in the background).

Fat is collected in a specially designed canister (fig. 2) and then transferred into smaller receptacles, typically 10 to 20 cc syringes, which are centrifuged for 2 to 3 minutes. This separates the components into oil, water and the cellular fraction, consisting mainly of fat and stem cells. The oil and water are then discarded and the cellular fraction is preserved. The cellular fraction is transferred into 1, 5 or 10 cc syringes depending on the volume to be injected and the recipient site (fig.3). The donor site incisions are then closed with absorbable sutures and small dressings applied.

Fig. 3: The different filtration phases: (right) the aspirated fluid transferred from the collecting container into syringes; (middle) after centrifugation, separation of the aspirated fluid into a water layer at the bottom, cellular fraction in the middle, and the oil layer on top; (left) after the water and oil have been discarded, the cellular fraction is ready for injection.

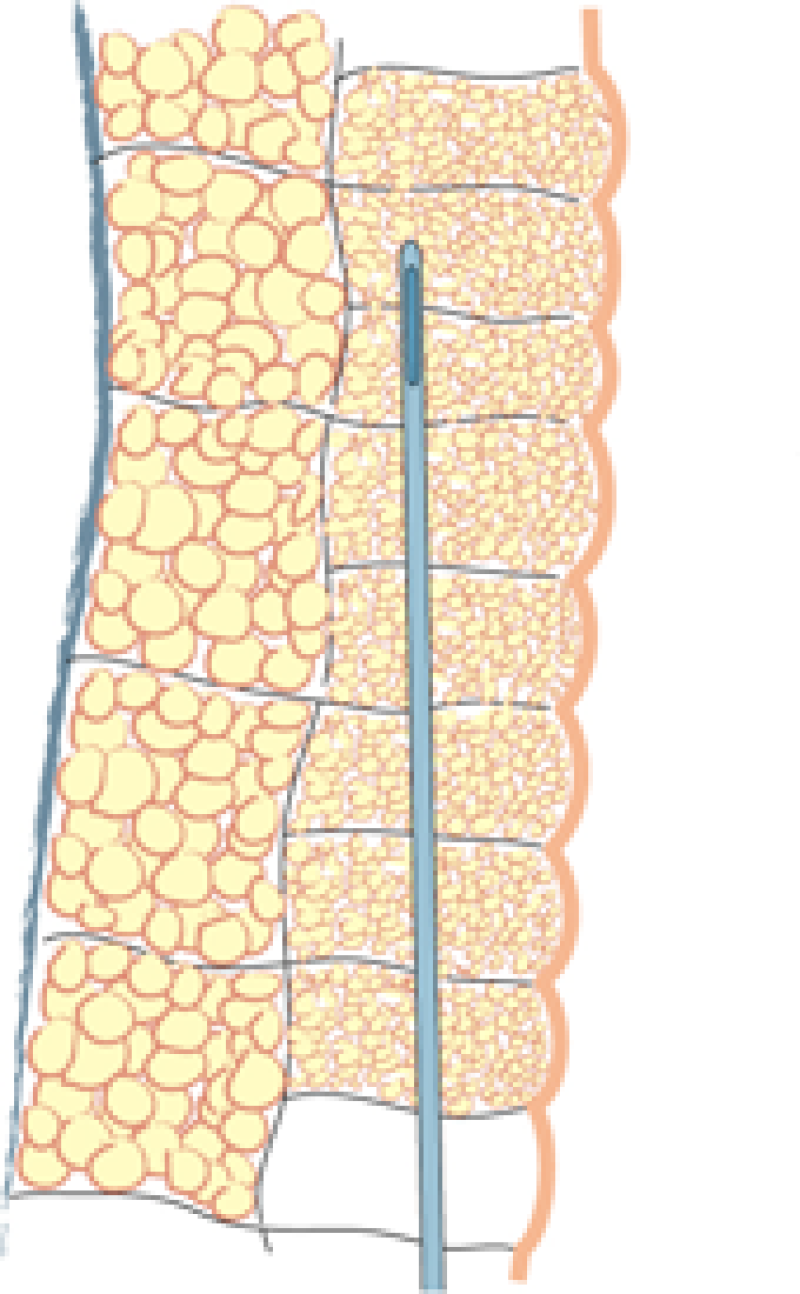

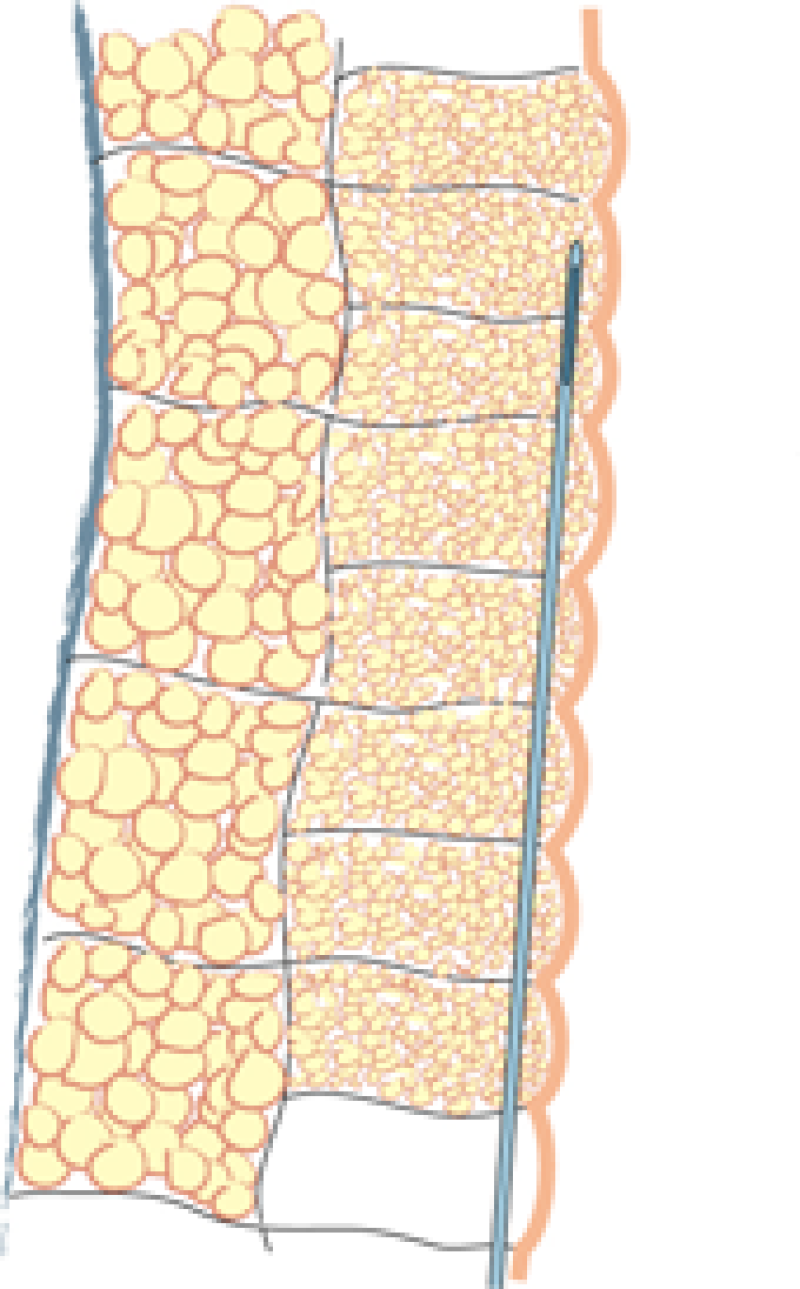

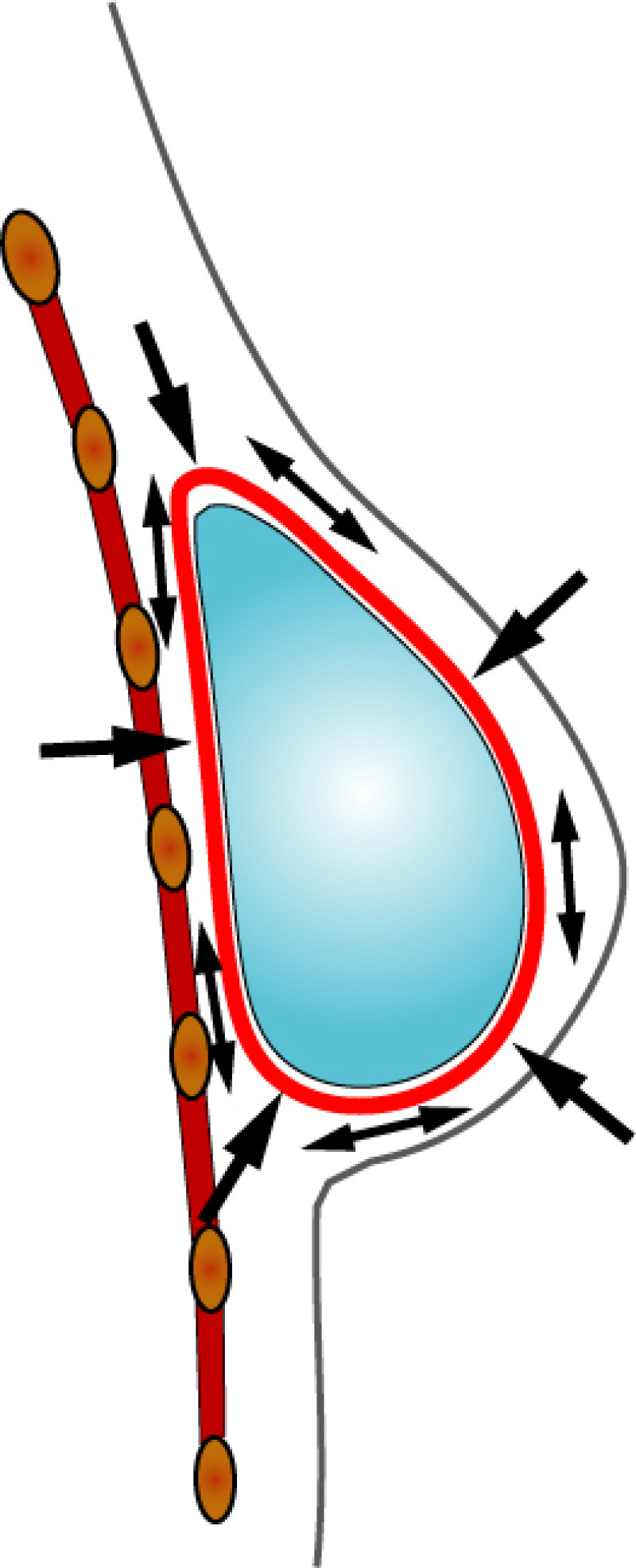

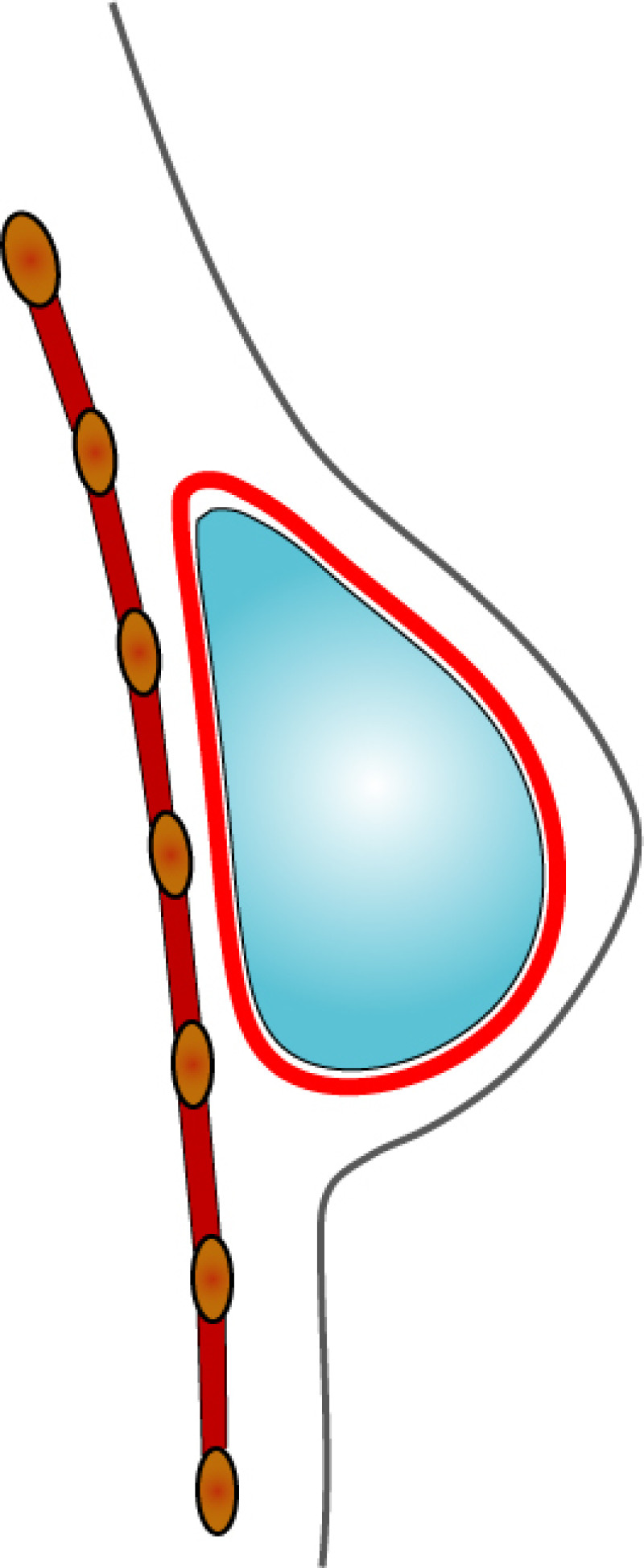

The fat is injected through cannulas that measure only 1 to 2.5 mm in diameter (fig. 4). This leaves virtually no scarring at the recipient site. The subcutaneous layer is injected by making hundreds or thousands of passes through the same incision and depositing microscopic particles of fat on each occasion. This creates multiple small tunnels, in opposing directions, throughout the soft tissue layer.

Fig. 4: typical injection canula

The injected fat initially survives by receiving oxygen and nutrients from its surroundings but this source is gradually depleted. At the same time, new blood vessels are growing towards the fat grafts (neo-angiogenesis), which are sending out distress signals. If the fat particles are too large (more than 3mm) or grouped too closely together, the blood vessels will not be able to reach them in time. The central part of the fat graft then remains de-vascularized and will die. Any dead fat turns into oil and the body isolates this by creating a cyst. Cysts may be spontaneously resorbed but if they are too big, they have to be surgically removed.

Further details of the technique are available at: www.lipofilling.com

Pre-operatively

It is vitally important that you discuss your expectations. In many cases two or three attempts at lipofilling may be necessary to achieve the desired effect. Unfortunately, approximately 50% of the injected fat is reabsorbed after each procedure and every patient needs to be aware of this.

Different scientific studies report fat survival rates of between 30 and 75%. Fat loss is due to trauma during surgery, deposits that are too large, apoptosis (programmed cell death) or other destructive cellular mechanisms. This means that overcorrection may be necessary but, the volume of fat that can be injected on one occasion is limited by the thickness and laxity of the soft tissue at the recipient site.

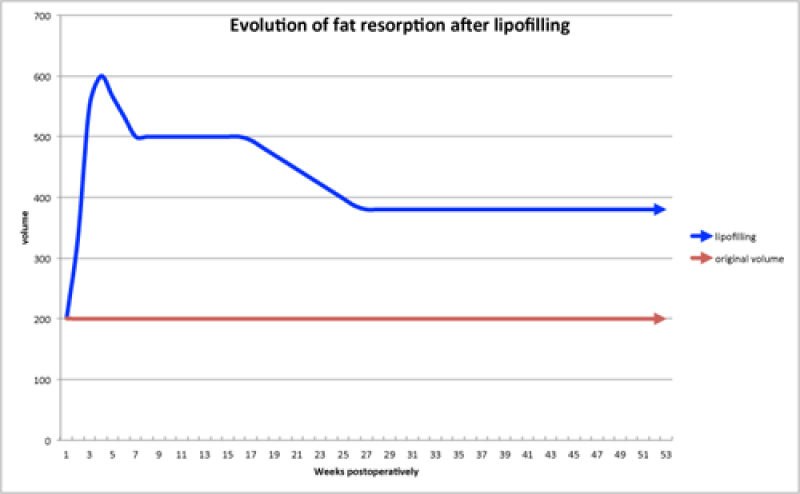

In general, there are two significant volume decreases following surgery (fig. 5):

The first is at approximately 3 weeks, when the post-operative fluid accumulation (oedema) settles.

The second occurs 4 to 6 months later as dead fat cells are reabsorbed by the body.

Fig. 5

Fig. 5: A graph indicating the reabsorption pattern of structural fat grafts: the first decrease is due to oedema settling and the second decrease is due to reabsorption of the dead fat cells. |

The fat cells that survive add volume to the area that lasts a lifetime but hormonal and weight changes may be responsible for future gains or losses.

To improve the surgical outcome, patients are encouraged not to smoke. Smoking decreases fat graft survival and increases the risk of complications, particularly delayed wound healing.

Post-operatively

Many patients experience areas of numbness post-operatively. This is related to swelling, mild trauma to the sensory nerves and the fact that local anaesthetic was administered. In addition, it is very common to develop bruising in the areas where the fat has been harvested and injected.

You will be asked to wear special compression garments after your surgery. These reduce swelling and bruising at the donor sites and the pressure also facilitates skin retraction and re-attachment of the underlying soft tissues. The compression garments are worn continuously, day and night, for 4 to 6 weeks. They may be removed briefly to wash or shower.

Do not place any ice or constrictive clothing, e.g. a bra, over the recipient area for 3 weeks. This enables the new budding blood vessels to penetrate the fat grafts. Smoking also stops the formation of these blood vessels and is completely forbidden.

You may need to take regular analgesia for a few days as lipofilling can cause some discomfort. In addition, refrain from driving until you feel comfortable and able to perform an emergency stop, if necessary. You should not do any housework or heavy lifting for at least 7 days. Most patients return to work 10-14 days following their surgery but sport should be avoided for at least 4 weeks.

Post-operative complications

Common sequelae

Discomfort

Transient numbness

Bruising

Swelling

General complications

Haematoma (<1%) which may require a return to theatre

Wound infection (<1%)

Seroma (<5%)

Hypertrophic scars

Complications specific to this procedure

Subcutaneous cysts, nodules or scarring

Fat reabsorption requiring additional surgery

Advantages and disadvantages

Advantages

Improvement at both the recipient site and the area from where fat is harvested.

Surviving fat is permanent.

A completely natural material.

Day surgery, minimal discomfort and a short recovery.

Minimally invasive, with a low risk of complications.

Small scars at the donor site and no additional scars at the recipient site.

Improves the quality of the overlying skin. This can be particularly important following radiation damage or in facial rejuvenation procedures.

Disadvantages

Repeated procedures may be necessary.

Lipofilling only adds volume, not additional skin. If this is required, for example after breast cancer surgery, local or distant flaps cannot be avoided.

Lipofilling is not possible if you are very thin.

Hormonal or weight changes may be responsible for future gains or losses.

Lipofilling may not be covered by your insurance policy. Please check.

References

Coleman SR, Saboeiro AP. Fat grafting to the breast revisited: safety and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119(3):775e85.

Spear SL, Newman MK. Fat grafting to the breast revisited: safety and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119(3):786e7.

Khouri R, Del Vecchio D. Breast reconstruction and augmentation using pre-expansion and autologous fat transplantation. Clin Plast Surg. 2009;36(2):269-80.

Illouz YG, Sterodimas A. Autologous fat transplantation to the breast: a personal technique with 25 years of experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(5):706-15.

Petit JY, Lohsiriwat V, Clough KB, Sarfati I, Ihrai T, Rietjens M, Veronesi P, Rossetto F, Scevola A, Delay E. The oncologic outcome and immediate surgical complications of lipofilling in breast cancer patients: a multicenter study--Milan-Paris-Lyon experience of 646 lipofilling procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(6):1317.

Rigotti G, Marchi A, Stringhini P, Baroni G, Galiè M, Molino AM, Mercanti A, Micciolo R, Sbarbati A. Determining the oncological risk of autologous lipoaspirate grafting for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34(4):475-80.

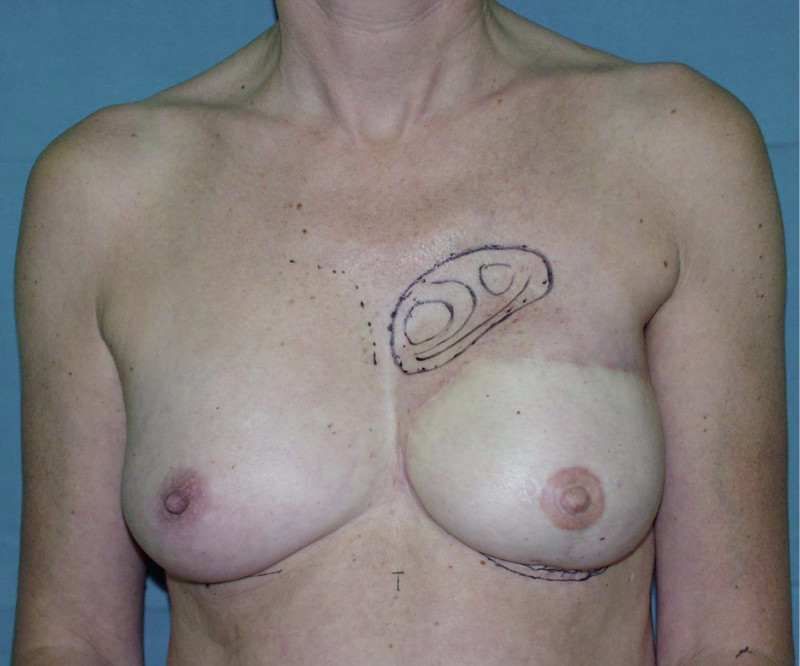

Lipofilling in breastreconstruction

Contour improvement

Regardless of the reconstruction technique, autologous tissue (fig. 1) or implants (fig. 2), the general shape and contour of the breast can be improved by adding small quantities of fat.

Fig. 1(a)

Fig. 1(b)

Fig. 1(c)

Fig. 1: (a) DIEAP flap breast reconstruction with hollowing in the décolleté area. (b,c) Result after lipofilling. |

Fig. 2(a)

Fig. 2(b)

Fig. 2(c)

Fig. 2: (a) Bilateral implant based breast reconstruction. (b) Improvement of both breasts using lipofilling. |

Contour improvement and contralateral breast augmentation

Instead of detaching and remodeling the entire flap in a secondary operation (through the same scars), flap remodeling is now performed by local liposuction to remove excess of volume and lipofilling in order to locally add some volume. In addition, a simultaneous augmentation of the other breast can be performed.(fig. 3)

Fig. 3(a)

Fig. 3(b)

Fig. 3: (a) Left DIEAP flap reconstruction. Remodeling by liposuction and lipofilling. (b) Post-operative appearance after remodeling of the left breast and lipofilling-augmentation of the right breast. |

Lipofilling after breast conserving surgery

If only small amounts of breast volume are missing, the depression can easily be filled up by one or more short sessions of lipofilling (fig. 4, 5). If the overlying skin is too tight as a result of radiotherapy, an initial low volume lipofilling is performed just below the skin in order to regenerate elasticity of the irradiated skin. In later procedures, volume is restored once expansion of tissues is possible.

Fig. 4(a)

Fig. 4(b)

Fig. 4(c)

Fig. 4(d)

Fig. 4: (a, b) Satus after tumorectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy of the left breast (arrow). (c, d) Status 1 year after simple lipofilling of the defect. The skin color and elasticity have improved. |

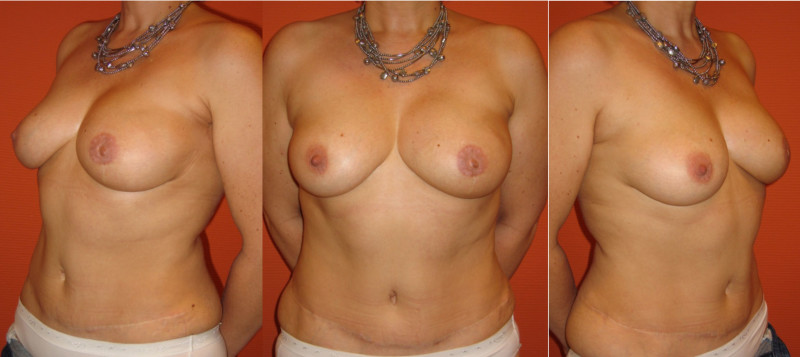

Fig. 5 (a)

Fig. 5(b)

Fig. 5(c)

Fig. 5: (a) Pre-operative view of a woman diagnosed with a BRCA-2 gene mutation after tumorectomy of the left breast. (b) Status after bilateral areola-sparing mastectomy, bilateral immediate breast reconstruction by DIEAP flaps, nipple reconstruction and tattoo. (c) an augmentation of the volume of the flap/breast can easily be obtained by simple lipofilling (280cc of fat was injected on each side) |

Referenties

Sommeling CE, Van Landuyt K, Depypere H, Van den Broecke R, Monstrey S, Blondeel PN, Morrison WA, Stillaert FB. Composite breast reconstruction: Implant-based breast reconstruction with adjunctive lipofilling. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017 Aug;70(8):1051-1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.05.019. Epub 2017 May 22. PMID: 28599842.

Spear SL, Wilson HB, Lockwood MD. Fat injection to correct contour deformities in the reconstructed breast. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;116(5):1300e5.

Rigotti G, Marchi A, Galie M, Baroni G, Benati D, Krampera M, et al. Clinical treatment of radiotherapy tissue damage by lipoaspirate transplant: a healing process mediated by adipose-derived adult stem cells. Plast Reconstr Surg; 2007;119(5):1409e22.

Lohsiriwat V, Curigliano G, Rietjens M, Goldhirsch A, Petit JY. Autologous fat transplantation in patients with breast cancer: "silencing" or "fueling" cancer recurrence? Breast. 2011;20(4):351-7.

Coleman SR, Saboeiro AP. Fat grafting to the breast revisited: safety and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119(3):775e85.

Spear SL, Newman MK. Fat grafting to the breast revisited: safety and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119(3):786e7.

Khouri R, Del Vecchio D. Breast reconstruction and augmentation using pre-expansion and autologous fat transplantation. Clin Plast Surg. 2009;36(2):269-80.

Illouz YG, Sterodimas A. Autologous fat transplantation to the breast: a personal technique with 25 years of experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(5):706-15.

Petit JY, Lohsiriwat V, Clough KB, Sarfati I, Ihrai T, Rietjens M, Veronesi P, Rossetto F, Scevola A, Delay E. The oncologic outcome and immediate surgical complications of lipofilling in breast cancer patients: a multicenter study--Milan-Paris-Lyon experience of 646 lipofilling procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(6):1317.

Rigotti G, Marchi A, Stringhini P, Baroni G, Galiè M, Molino AM, Mercanti A, Micciolo R, Sbarbati A. Determining the oncological risk of autologous lipoaspirate grafting for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34(4):475-80.

VII. Autologous breast reconstruction

Full breast reconstruction can be done by transplanting large pieces of your own tissue. This tissue is usually taken from a place where you have some extra subcutaneous fat tissue. Usually this is the region of the lower abdominal wall, but this can also be perfectly transplanted from the regions of the buttock, the love handles, the thighs, the back, etc. It is important that with the modern techniques of perforator flap surgery only the skin and the subcutaneous fat tissue is removed and the underlying muscle is completely preserved.

A. Autologous Breast Reconstruction - General

Introduction

Breast reconstruction using autologous tissue currently represents the ‘gold standard’ and patients with excess tissue on their abdomen, buttock, or thighs are suitable candidates for this option. The reconstructed breast looks natural, feels soft and is warm to touch. The scars fade over time and the volume of the breast changes correspondingly with weight fluctuations. Autologous tissue reconstruction therefore consistently delivers the best, most stable, long term results.

Autologous tissue can be irradiated, if necessary, as part of breast cancer treatment, though the radiation may harden some of the fat and reduce the overall volume of the reconstruction.

Evidence shows that autologous tissue reconstruction is also more cost effective in comparison to other techniques, as further surgery is rarely required. This benefits both the patient and their health care system (public or private).

The main drawback of autologous tissue reconstruction is the prolonged operating time, since the initial surgery is more complex. There is also the risk of partial or complete flap loss, if problems occur. Patients need to be able to accept the additional scars elsewhere on their body.

Any patient who is fit enough and willing to endure a long surgical procedure is potentially suitable for autologous reconstruction. Poor candidates are those who are ill-informed or demotivated. Smokers must stop 6 months before surgery.

The abdomen: a DIEAP or SIEA flap

If a large amount of skin and fat are required, the DIEAP (Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery Perforator) flap is the ideal choice. Many women have excess tissue between the umbilicus and pubic area, allowing reconstruction of large breasts and tension-free donor site closure. The fat from this region is soft, resembling the natural consistency of the breast. The skin texture and colour are also similar and re-connecting the sensory nerves to this tissue may be possible.

A DIEAP flap can still be transferred and used as a ‘vascularized matrix’ if there is skin excess but insufficient fat at the donor site. Lipofilling is later used to increase the volume of the flap and achieve breast symmetry.

If it becomes apparent during surgery that the blood supply to this tissue is mainly from the superficial inferior epigastric artery and veins, the surgeon can raise a SIEA (Superficial Inferior Epigastric Artery) flap instead. This is identical to the DIEAP flap but is associated with even lower donor site morbidity because the deep muscle fascia is not opened.

For both abdominal flaps the donor site scar is positioned sufficiently low enough that it can be covered by underwear or a swimming costume.

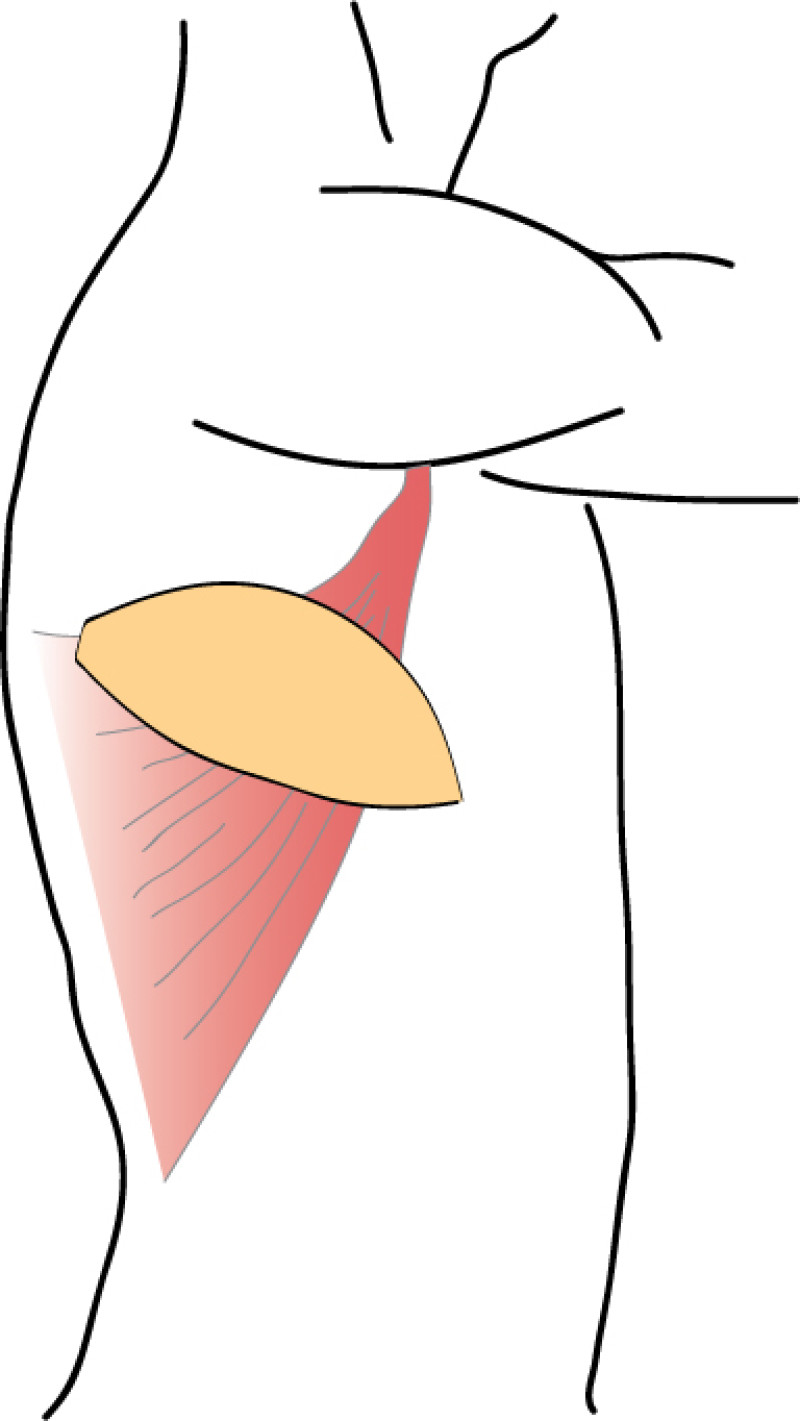

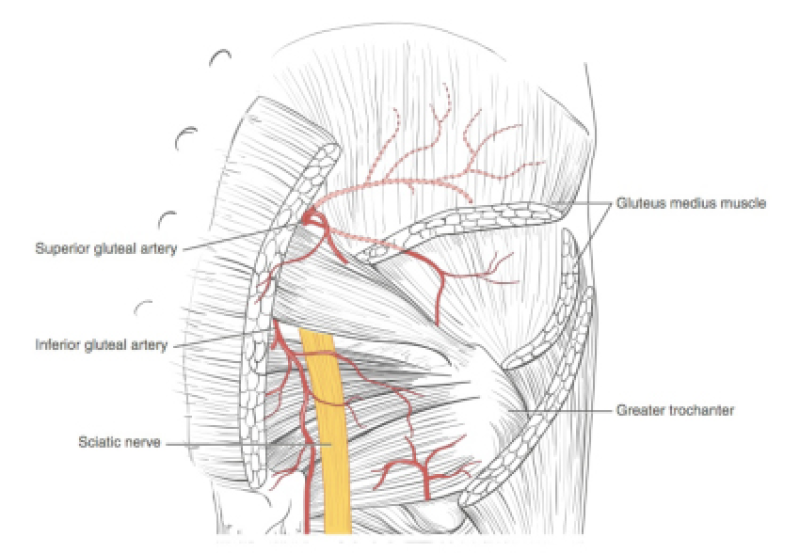

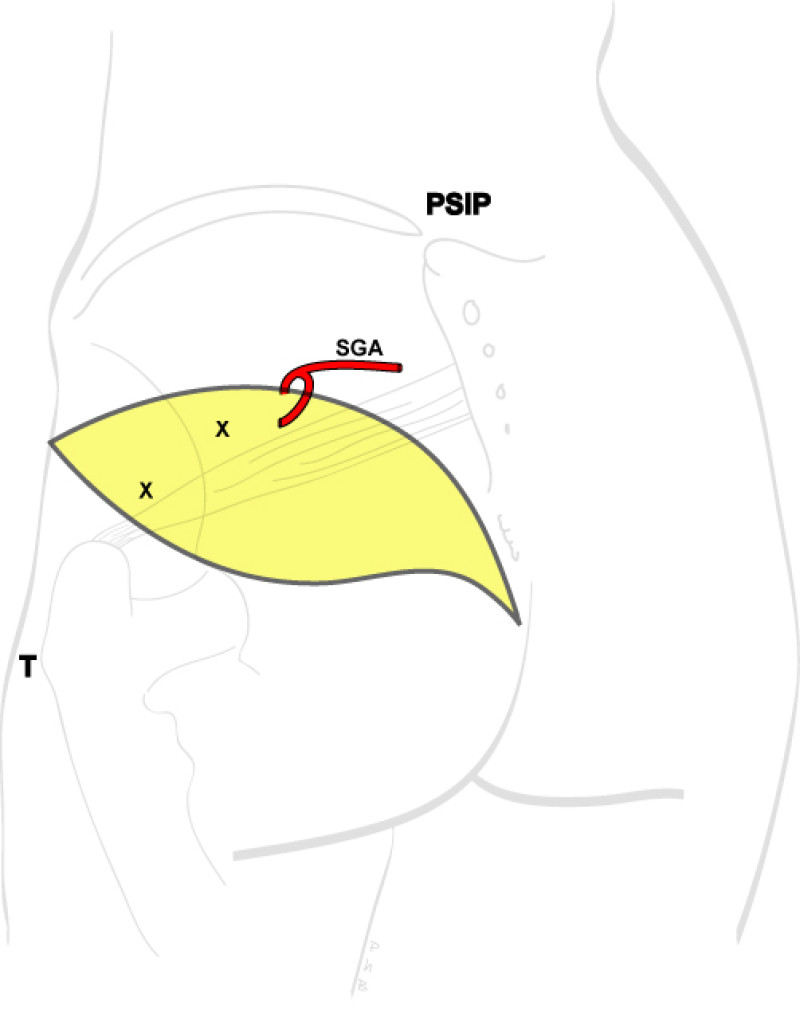

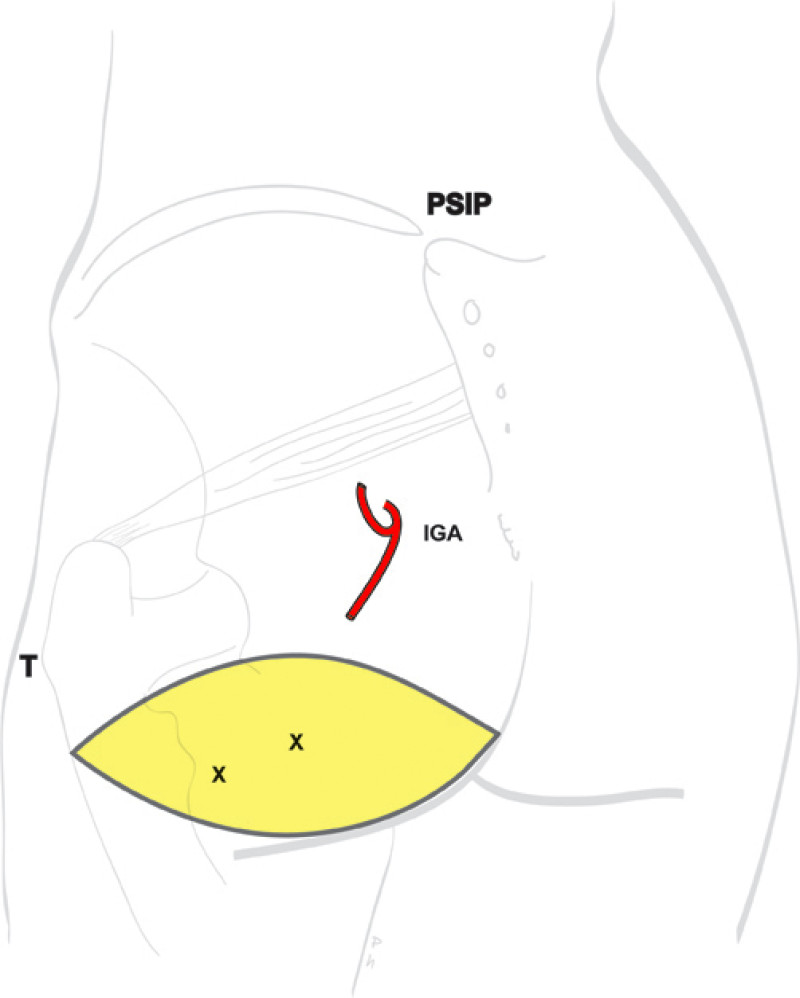

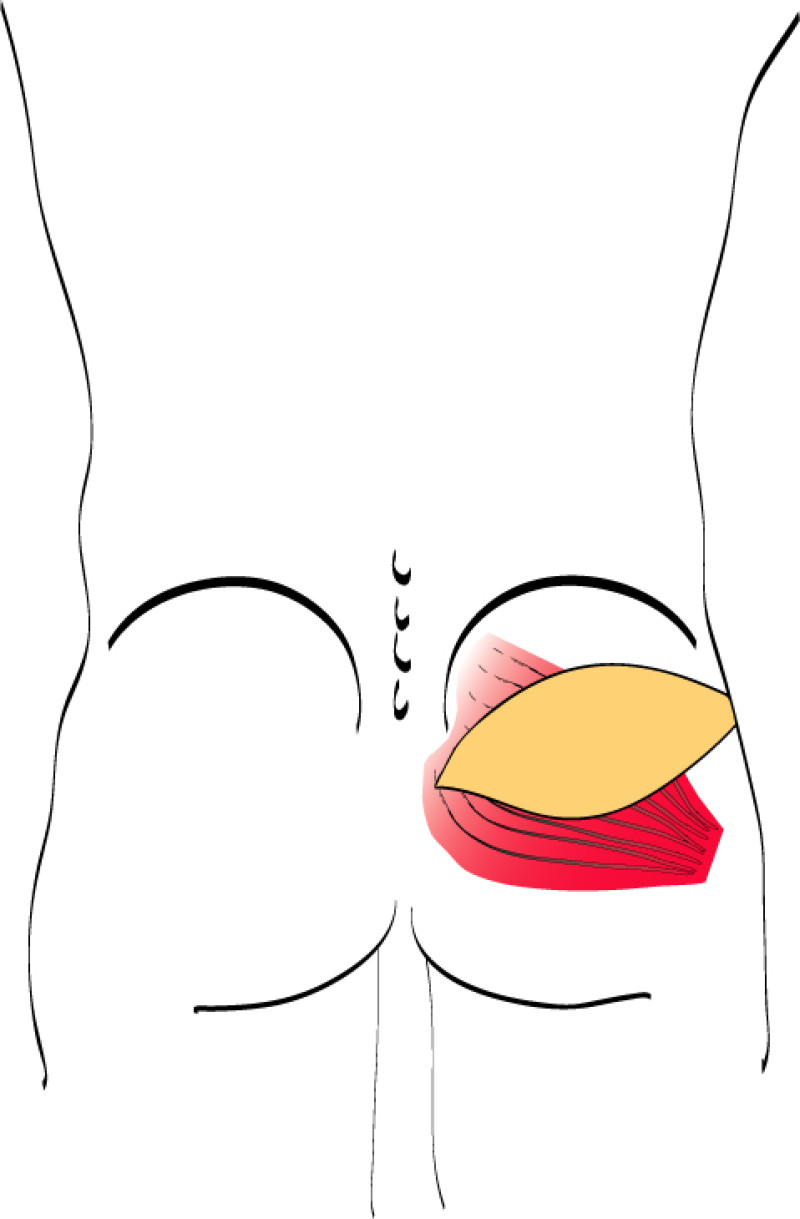

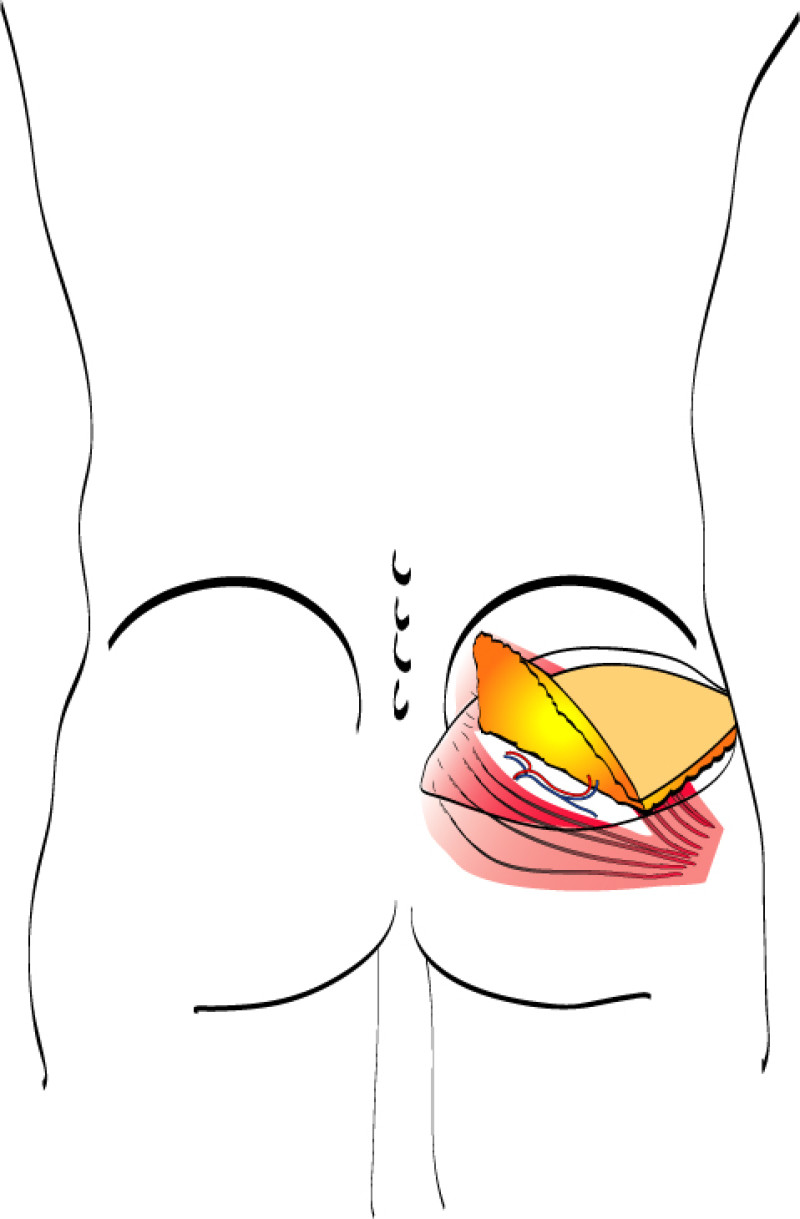

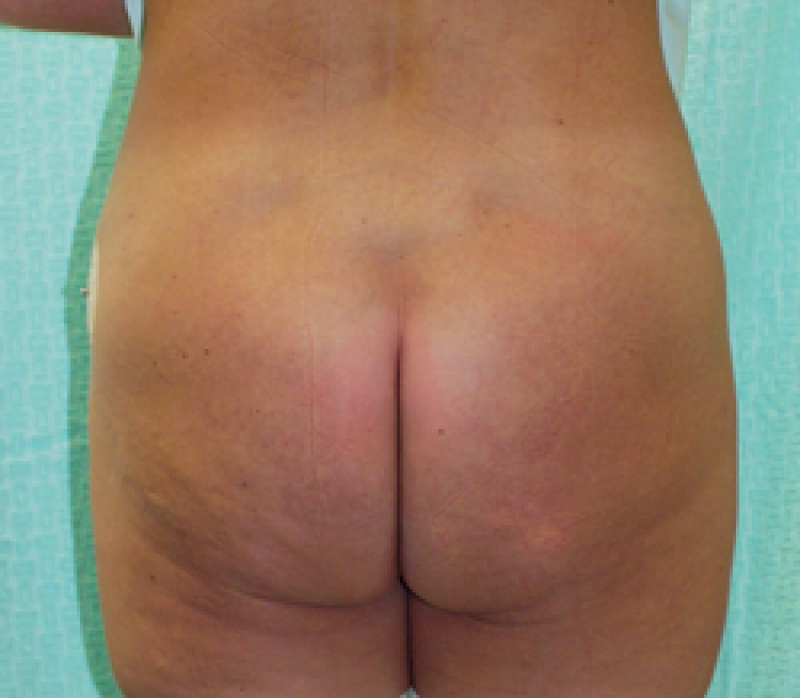

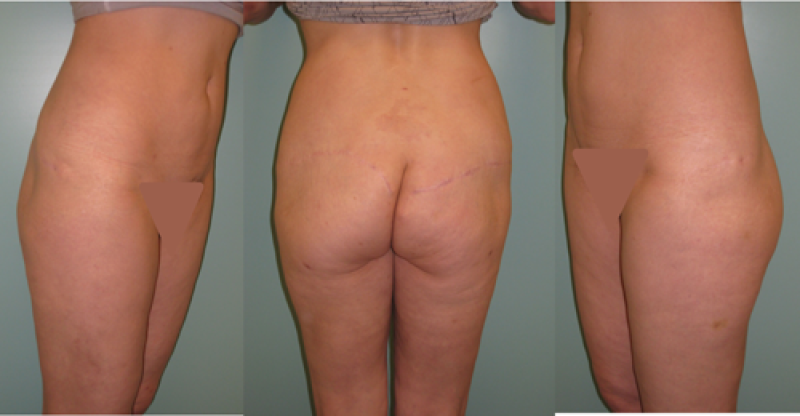

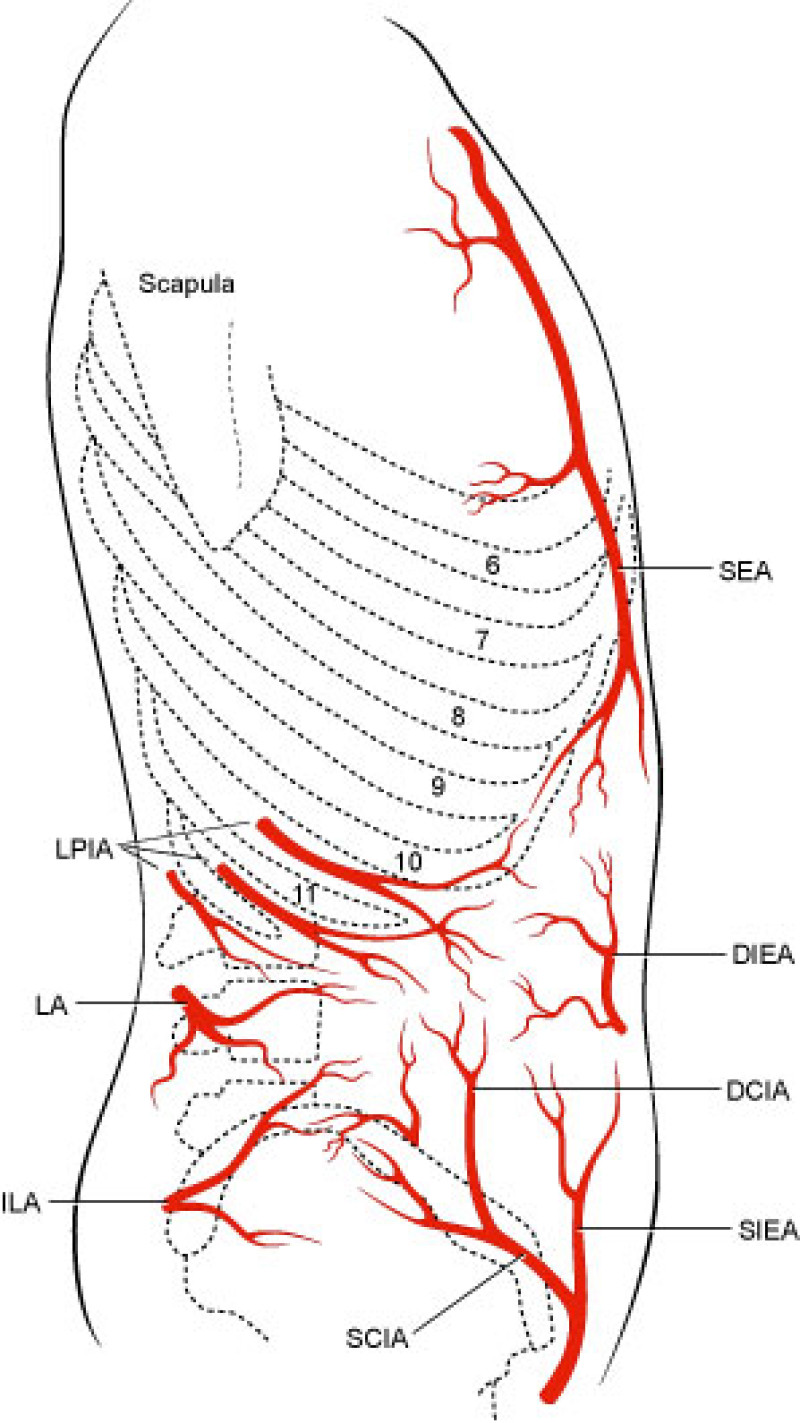

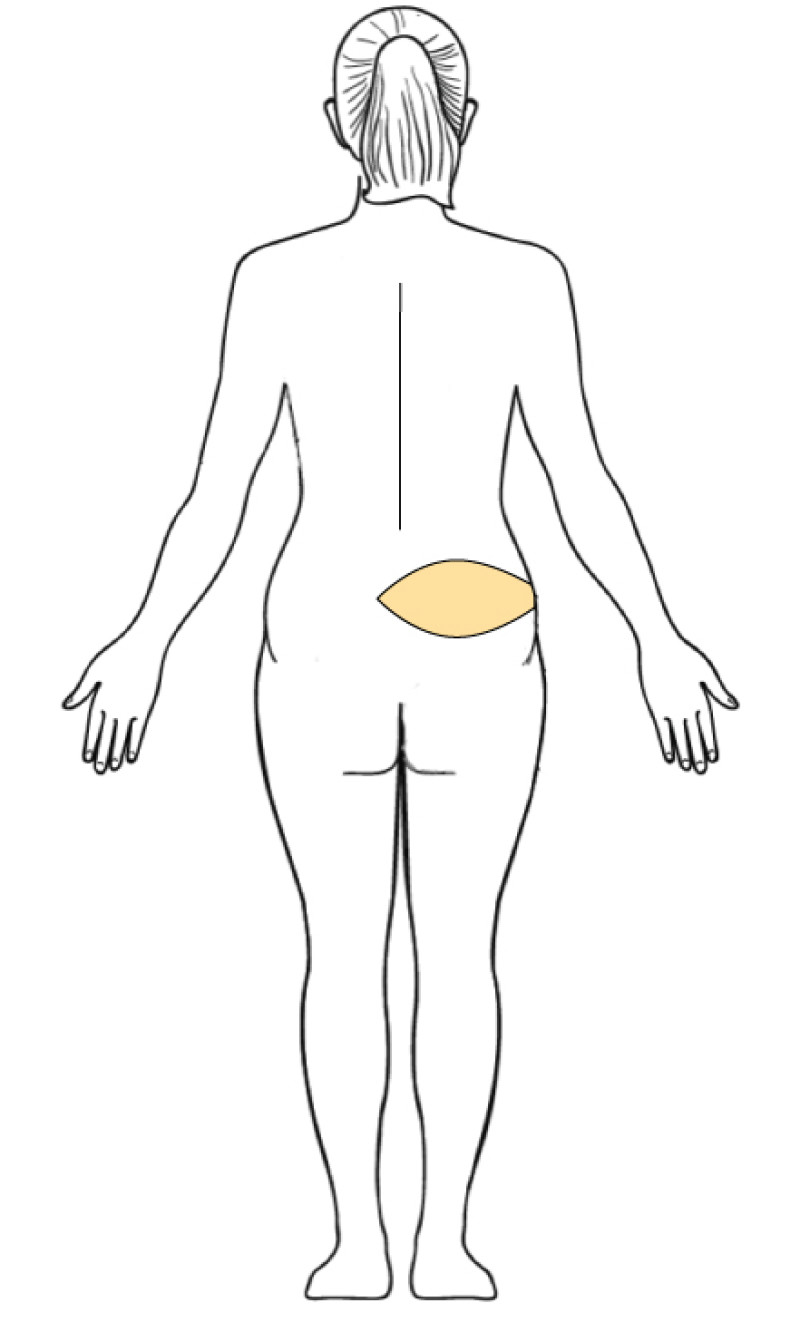

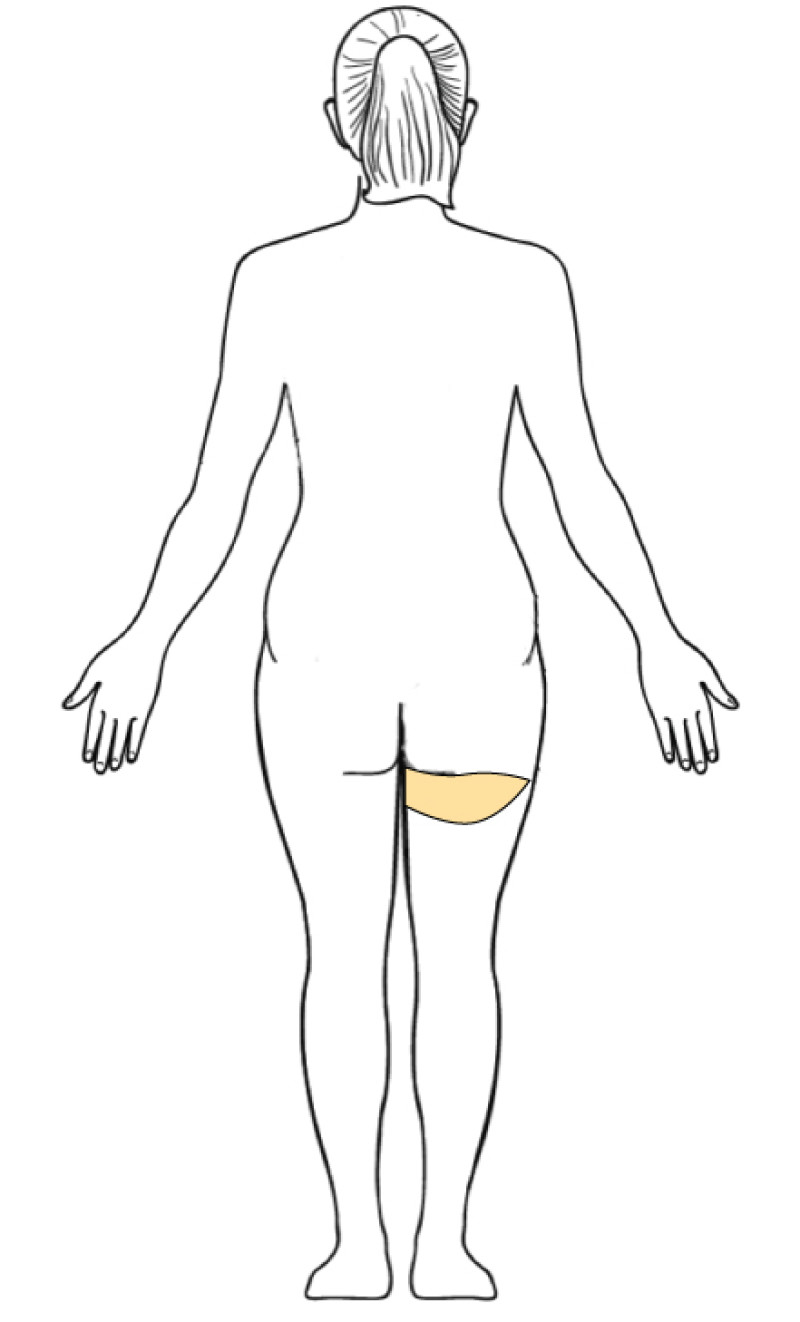

Buttock: the SGAP and IGAP flap

The superior gluteal artery perforator (SGAP) flap and the inferior gluteal artery perforator (IGAP) flap are alternative options if there is insufficient abdominal donor tissue or extensive abdominal scarring. Gluteal flaps are also a possibility when the abdomen has already been used (tertiary reconstruction).

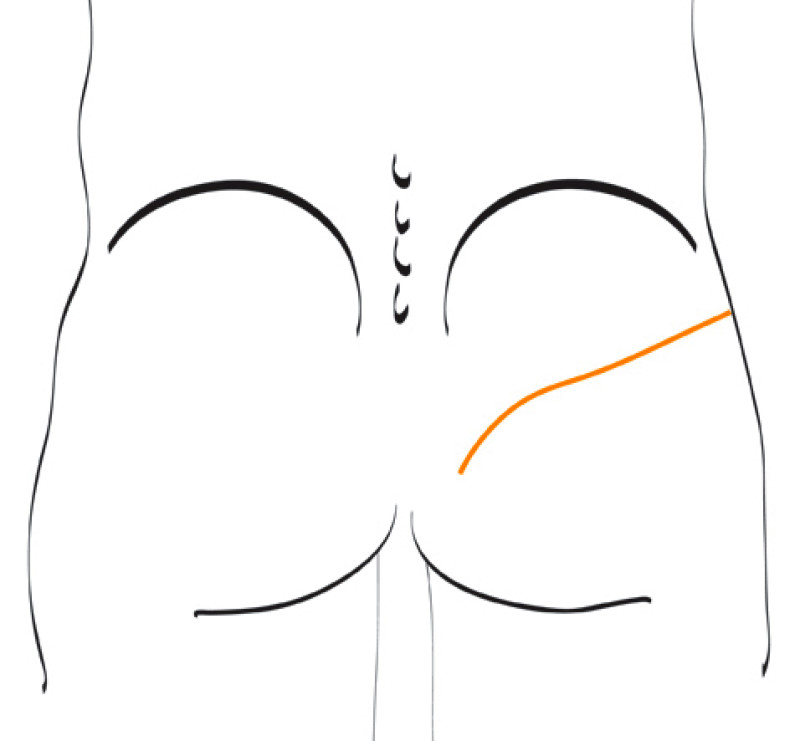

Women with an asthenic body habitus are potentially suitable and even those weighing less than 50 kg are likely to have sufficient fat on the superior part of their buttock. The donor site scar of an S-GAP flap can easily be hidden, although some asymmetry in the gluteal region may be noticeable post-operatively.

The I-GAP flap is an option for patients with some sagging of their buttocks. Dissection of an I-GAP flap can however expose the sciatic nerve or motor nerves to the gluteal muscle and the resulting scar can also be more difficult to conceal.

The back

The thoracodorsal artery perforator (TDAP) flap and Latissimus Dorsi musculocutaneous (LD) flap can also be used for complete breast reconstruction but require the simultaneous insertion of a breast implant to provide sufficient volume. This therefore combines complex flap surgery with the disadvantages of implant based reconstruction and we therefore reserve the back as a rescue option for previously failed breast reconstruction.

Another potential donor site in this area is the lower back. The lumbar area, just above the iliac crest has a thick and pliable layer of fat. A lumbar artery perforator (LAP) flap can be harvested. This can easily be shaped into a beautiful breast but involves complex microsurgery. The artery and vein supplying the flap are short, requiring an additional vessel graft from the groin, interposed between the donor and recipient vessels.

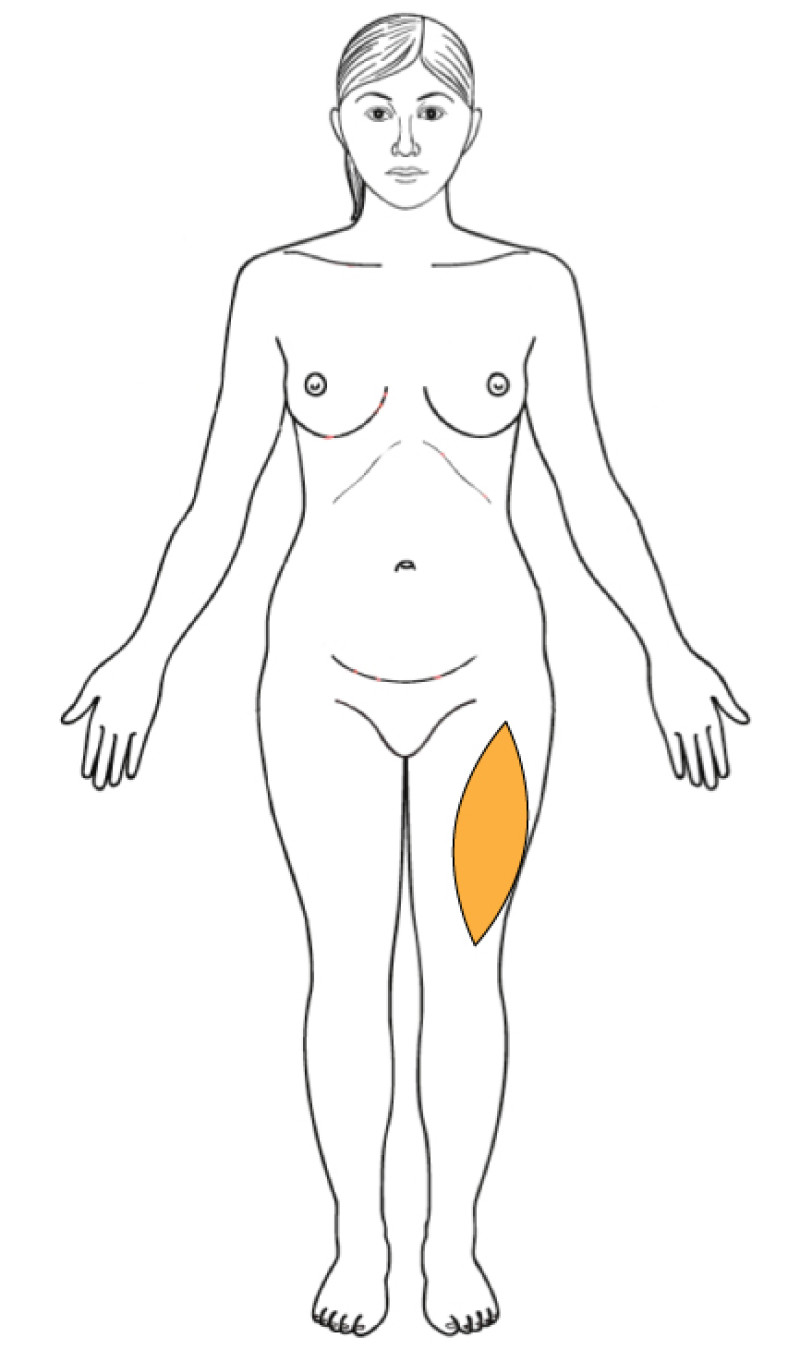

The upper thigh

Flaps based on the medial or lateral circumflex femoral artery perforators (MCFAP or LCFAP flap) can only be harvested if there is sufficient additional adipose tissue on either the medial or lateral side of the thigh. These flaps leave conspicuous scars that many women find unacceptable and should only be considered after other potential donor sites.

The groin

Flaps from the superficial (SCIAP) or deep circumflex iliac system (DCIAP) are very rarely used because of their small volume, unreliable blood supply and difficult dissection (particularly the deep system).

Flap options | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

DIEAP | First choice Large amount of skin and fat available | Scar between umbilicus & pubis |

SIEA | Alternative to DIEAP if the superficial system is dominant Reduced donor site morbidity | Scar between umbilicus & pubis Small, spastic artery Only ½ flap is reliable, unless the patient has a high BMI |

SGAP, IGAP | Second choice Sufficient donor site tissue frequently available SGAP donor site scar is easy to hide | Small skin paddle, therefore more suitable for primary breast reconstruction Tougher consistency, difficult to shape Discrepancy between the donor and recipient vessels Asymmetric donor site following flap harvest |

LAP | Bulky Easy to shape Large perforator, easy dissection | Short vessel length requiring interposition grafts Prolonged surgery Slightly increased risk of thrombosis |

LCFAP (-tfl or -vl) | Easy flap dissection | Large, conspicuous donor site scar |

MCFAP-grac | Easy flap dissection | Gracilis muscle is frequently harvested with the flap Limited flap volume Additional donor site morbidity includes: scar on the medial aspect of the thigh, displacement of the vulva, contour irregularities, lymphoedema of the limb. |

SCIAP and DCIAP | Donor site scar easy to hide | Limited flap volume Variable vascular anatomy |

Pre-operative planning

Appropriate patient selection is the key to achieving a successful outcome with elective microsurgical perforator flap breast reconstruction.

A complete history and physical examination are performed at the initial consultation. Comorbid medical conditions and any scarring at potential donor sites are noted. A previous abdominoplasty or abdominal lipectomy is an absolute contraindication to a DIEAP or SIEA flap and a past history of abdominal or gluteal liposuction is a relative contraindication. If a DIEAP/SIEA flap or gluteal flap is being considered, despite previous liposuction, a detailed preoperative duplex or CT-scan of the cutaneous vessels is essential.

A patient should be in general good health to withstand the prolonged surgery and anesthesia associated with free tissue transfer. Age is usually not a consideration but we prefer to operate on patients who are less than 85 years old. Obese patients are advised to lose weight to limit the incidence of perioperative complications.

Smokers must stop at least six months before surgery. Smoking causes a 10-fold increase in the risk of bleeding, infection and delayed wound healing. Patients should mention any regular medication that they are taking. Aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and herbal medications must be avoided for three weeks before surgery. You may also be advised to stop Tamoxifen because of the increased risk of developing a thrombosis and an embolism.

A thorough explanation of the procedure is provided, including possible risks and complications, at both the donor and recipient sites. The normal care pathway and typical post-operative recovery are outlined. Any remaining questions are answered and the patient’s motivation assessed. Anyone unsure about the procedure is given time for reflection or offered an alternative reconstructive option.

The preoperative investigations include a study of the vascular anatomy of most donor sites. For example, although it is possible to harvest a DIEAP flap without knowing the exact size and position of the perforators, we believe it is safer and faster to do so with this information beforehand. A CT angiogram is therefore routinely performed in DIEAP flaps, creating a three-dimensional map of the perforating vessels with their coordinates centered on the umbilicus. Not only the location and diameter of the vessels are evaluated but also the blood flow and arborisation of the individual side branches. This helps greatly with safe planning.

There is less variation in the vascular anatomy of gluteal flaps. Therefore pre-operative examination with a hand-held Doppler is usually sufficient.

The internal mammary vessels are also assessed, as they are our preferred recipient vessels in breast reconstruction.

Additional pre-operative investigations may be arranged if you have any associated medical problems.

It is advisable to avoid fibre-rich food the day before surgery and do not eat or drink after midnight. Prepare some food, drinks and pain medication for when you return home, especially if living alone. You may also want to arrange some domestic help during your recovery, either from family, friends or your medical insurer.

Avoid applying any lotions, creams or perfumes to your skin 24 hours before surgery. Bring some comfortable, loose, elastic clothing as your mobility will be reduced immediately afterwards. Your hospital stay normally lasts between 4 and 8 days, provided there are no complications.

Once admitted you will be asked to wash your skin with a disinfecting soap, put on compression stockings and shave your pubic area. Your surgeon will draw surgical markings and take pre-operative photographs. Nurses then escort you to the operating theatre.

B. The abdomen

Introduction

The most common donor site for autologous reconstruction is the lower abdomen, between the umbilicus (belly button) and the pubic area. The skin and fat in this region resemble the natural consistency of the breast and many women have excess tissue in this region. Removing it has the additional benefit of improving the aesthetic appearance of the abdominal wall.

There are a variety of ways to transfer this tissue and the TRAM (transverse rectus abdominis musculo-cutaneous) flap was first described in 1979. During the 1980’s and 1990’s this was the standard method of autologous breast reconstruction. Refinements in surgical technique now mean that it is possible to use this same donor area without sacrificing the underlying rectus abdominis muscle.

Methods of transferring the autologous tissue from the lower abdomen include;

The pedicled TRAM flap: The donor tissue is kept attached to the underlying rectus abdominis muscle. The muscle is divided at its lower end and rotated through a subcutaneous tunnel onto the chest wall. The origin of the muscle stays connected to the edge of the rib cage and therefore the blood supply to the tissue always remains intact.

The free TRAM flap: In this procedure only part of the rectus abdominis muscle is sacrificed but its blood supply is completely disconnected. The deep inferior epigastric vessels are divided in the groin and then microsurgically reconnected to similar vessels in the chest wall or in the arm pit. It takes about 60 minutes to re-establish the blood supply.

The DIEAP flap: The Deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flap preserves the entire rectus abdominis muscle. The blood vessels supplying the overlying skin and fat are carefully dissected. The deep inferior epigastric vessels are again divided in the groin and microsurgically reconnected to the vessels in the chest wall or arm pit. It also takes about 60 minutes to re-establish the blood supply.

1. Pedicled TRAM

The skin and fat of the lower abdomen between the umbilicus (belly button) and the pubic area are kept attached to the underlying rectus abdominis muscle. The muscle is divided at its lower end and rotated through a subcutaneous tunnel onto the chest wall. The origin of the muscle stays connected to the edge of the rib cage and therefore the blood supply to this tissue (superior epigastric artery) always remains intact.

There are two major disadvantages of the pedicled TRAM flap. Firstly, either one or both of the rectus abdominis muscles have to be sacrificed and this can lead to functional problems. Patients may notice a decrease in core strength during flexing or bending of the torso. Bulging of the abdominal wall or a hernia can also develop at the site of muscle harvest. Secondly, the blood supply to the overlying tissue is not always ideal because of the long distance it has to travel. Twisting of the muscle during transfer can also compromise the blood supply.

A pedicled TRAM flap therefore has a higher incidence of both partial necrosis and fat necrosis. In addition, it is more difficult to shape, and there is often a bulge in the upper abdomen corresponding to the subcutaneous tunnel. However, a pedicled TRAM is technically less challenging in comparison to a free TRAM or free DIEAP flap because no microsurgery is involved.

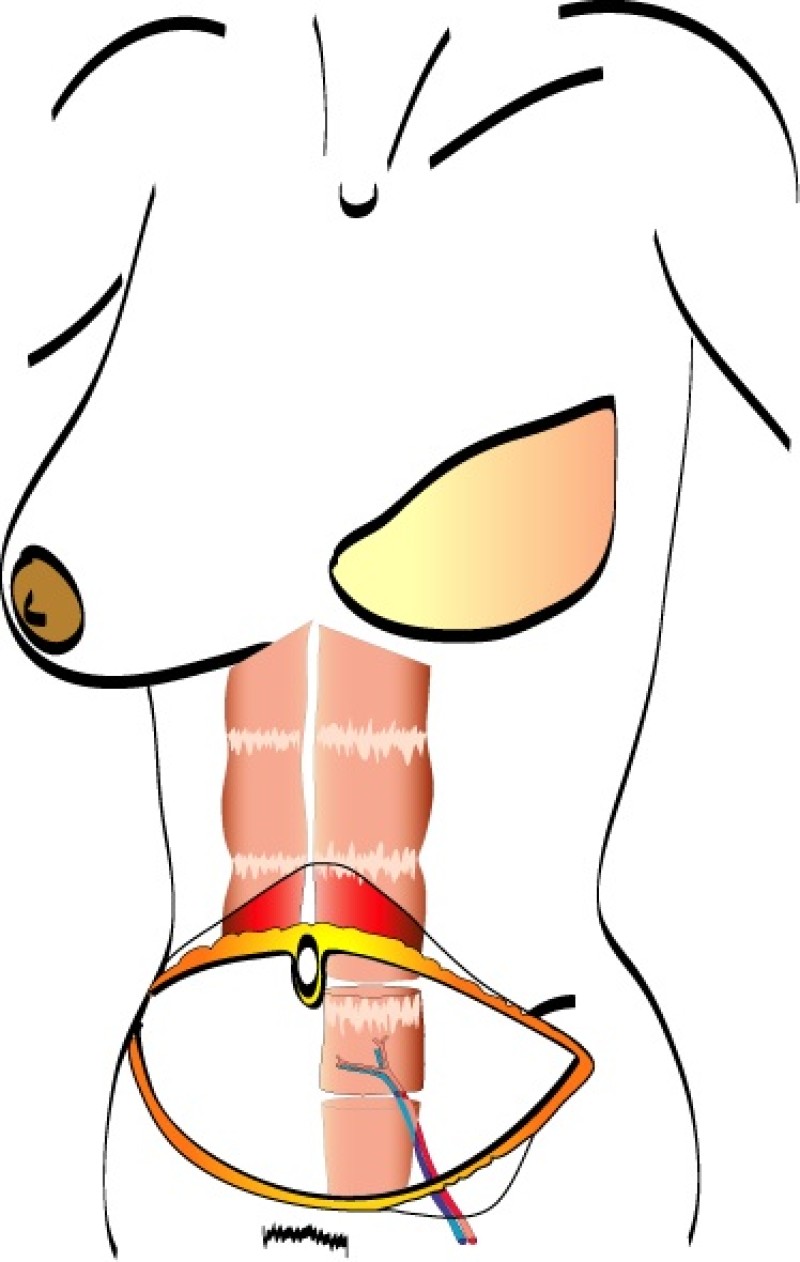

Fig. 1 (a)

Fig. 1 (b)

Fig. 1: The pedicled Transverse Rectus Abdominis Muscle (TRAM) flap: the flap is based on one or both rectus abdominis muscles (only right rectus muscle in this drawing) (a) and is transfered to the chest wall through a subcutaneous tunnel (b). |

Incidence of complications

Pedicled TRAM | |

Return to theatre | 2 |

Partial Flap Necrosis | 11.1 |

Fat Necrosis | 6.4 |

Total Flap Loss | 1.3 |

Seroma | 8 |

Haematoma | 2.2 |

Infection | 4.1 |

Abdominal Bulge | 6.9 |

Abdominal Hernia | 3.4 |

References

Holmstrom H. The free abdominoplasty flap and its use in breast reconstruction: an experimental study and clinical case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;13:423.

Hartrampf CR, Scheflan M, Black PW. Breast reconstruction with a trasverse abdominal island flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:216-225.

Moon HK, Taylor GL. The vascular anatomy of the rectus abdominis muscolo-cutaneous flaps based on the deep superior epigastric system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:815-822.

Nair N, Atisha DM, Streu R, Collins ED, Diehl K, Pearlman M, Alderman AK. An innovative approach to the primary surgical delay procedure for pedicle TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(4):173e-174e.

Berrino P, Santi P. Preoperative TRAM flap planning for postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 1988;21(3):264-72.

Bostwick J 3rd, Jones G. Why I choose autogenous tissue in breast reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1994;21(2):165-75.

Clugston PA, Gingrass MK, Azurin D, Fisher J, Maxwell GP. Ipsilateral pedicled TRAM flaps: the safer alternative? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(1):77-82.

2. Free TRAM

The free Transverse Rectus Abdominis Muscle (TRAM) flap was developed to address some of the concerns with the pedicled TRAM flap.

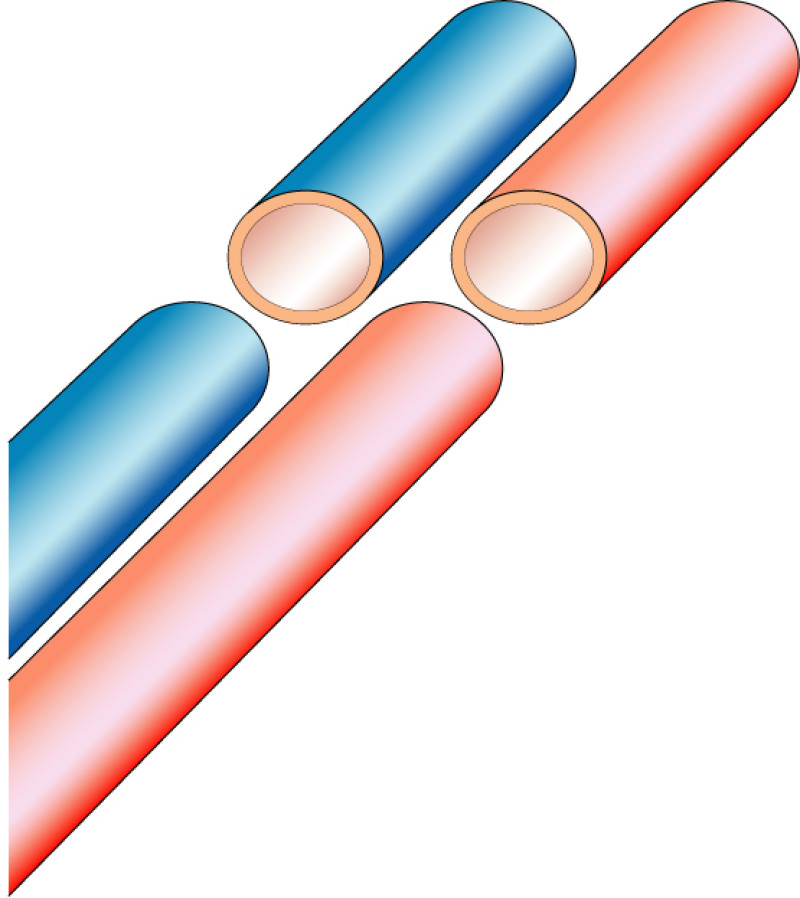

In a free TRAM flap the same amount of skin and fat are harvested from the abdominal wall, but only the lower part of the rectus abdominis muscle is sacrificed. Blood flow to the tissue is supplied by the deep inferior epigastric artery and vein which are divided in the groin and the TRAM flap completely detached from the patient (fig. 1).

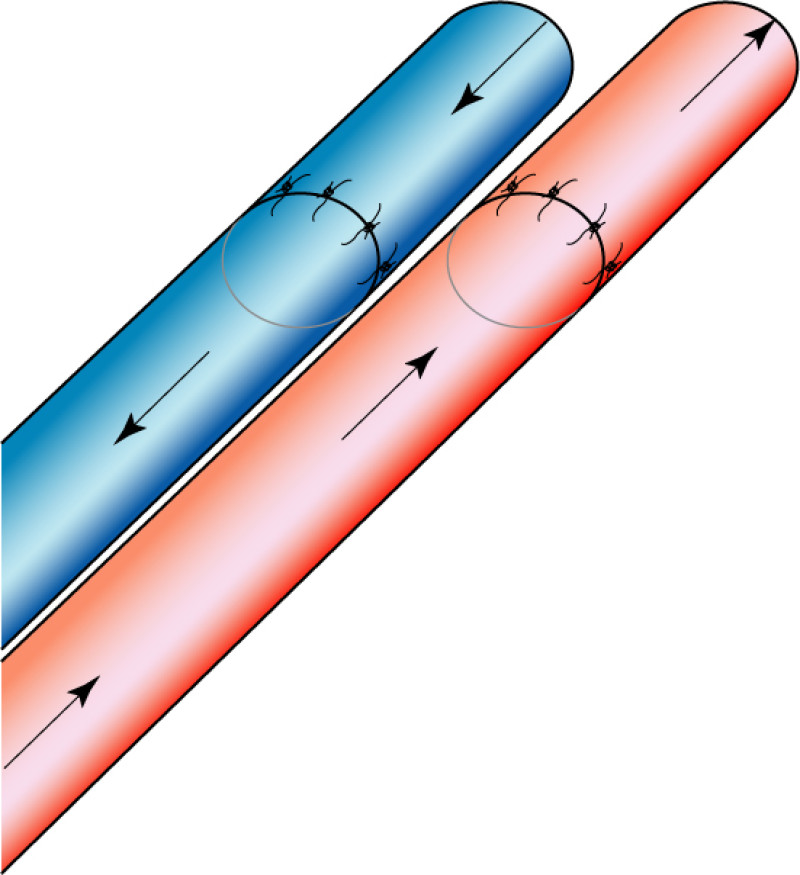

The tissue is transferred to the chest wall where both the artery and vein are reconnected to similar vessels, either in the armpit (thoracodorsal vessels) or beside the sternum (internal mammary vessels). These blood vessels have a diameter of 15 to 25 mm and are joined together under the operating microscope. This is very delicate, precise surgery which prolongs the operating time.

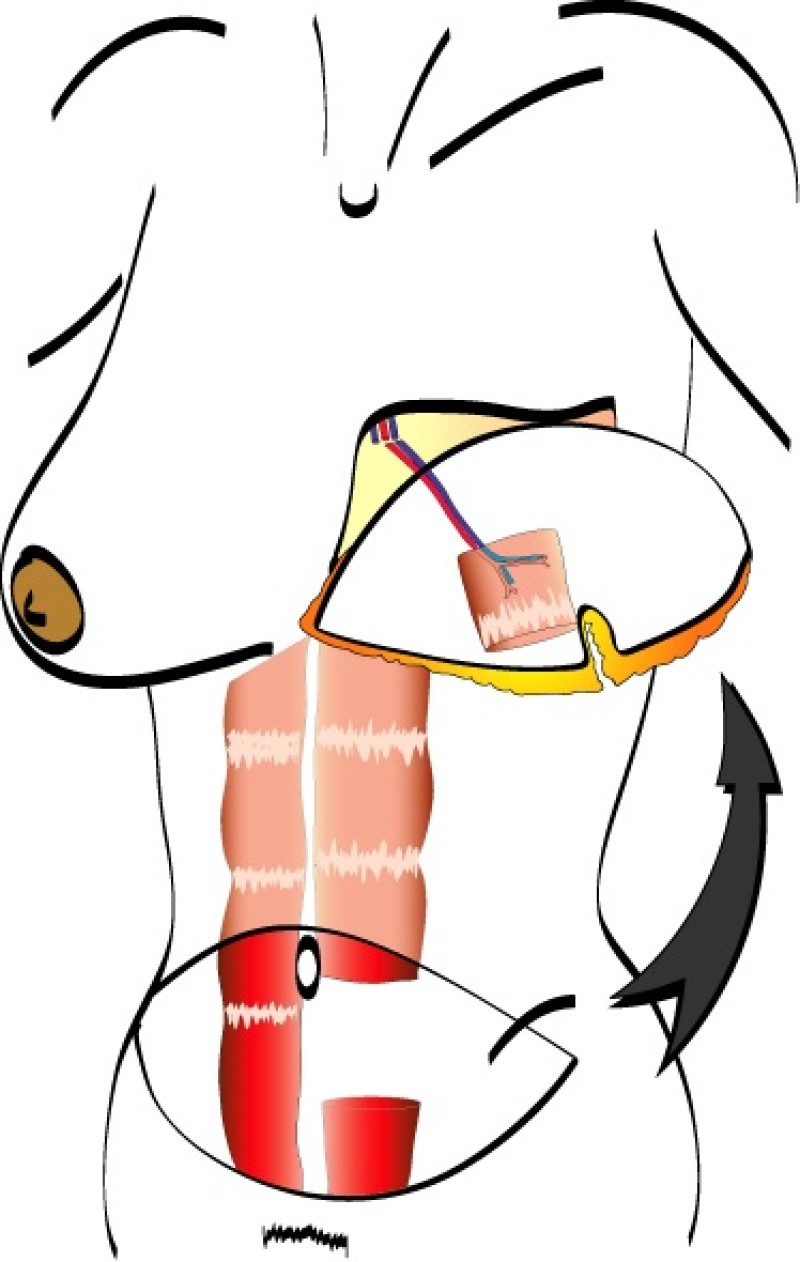

Fig. 1 (a)

Fig. 1 (b)

Fig. 1 (a) The free TRAM flap gets its normal blood flow from vessels coming from the groin (the inferior epigastric artery and vein); (b) These vessels are hooked up to recipient vessels through microsurgery. |

A similar amount of skin and fat can be utilised, but with a smaller piece of the rectus abdominis muscle. This is called a muscle sparing free TRAM flap (fig. 2). It causes less muscle weakness post-operatively and a lower incidence of abdominal wall problems.

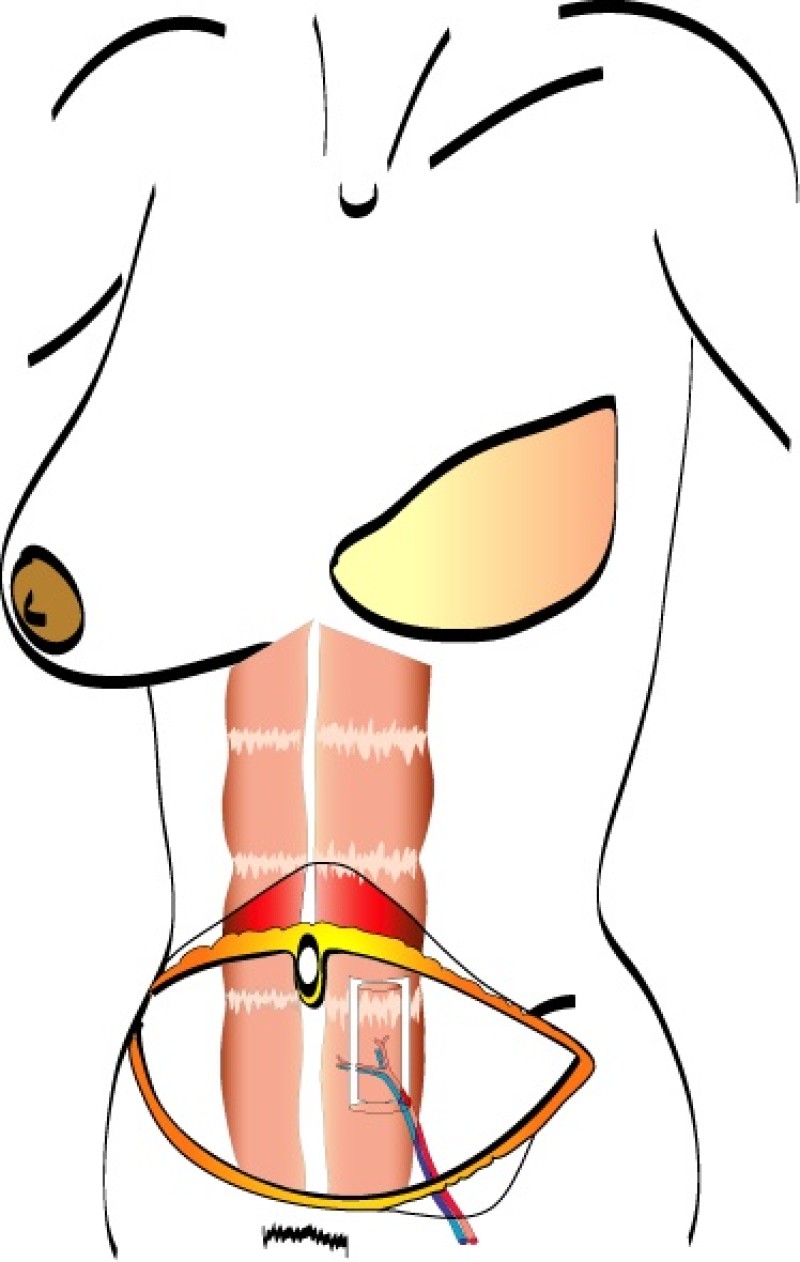

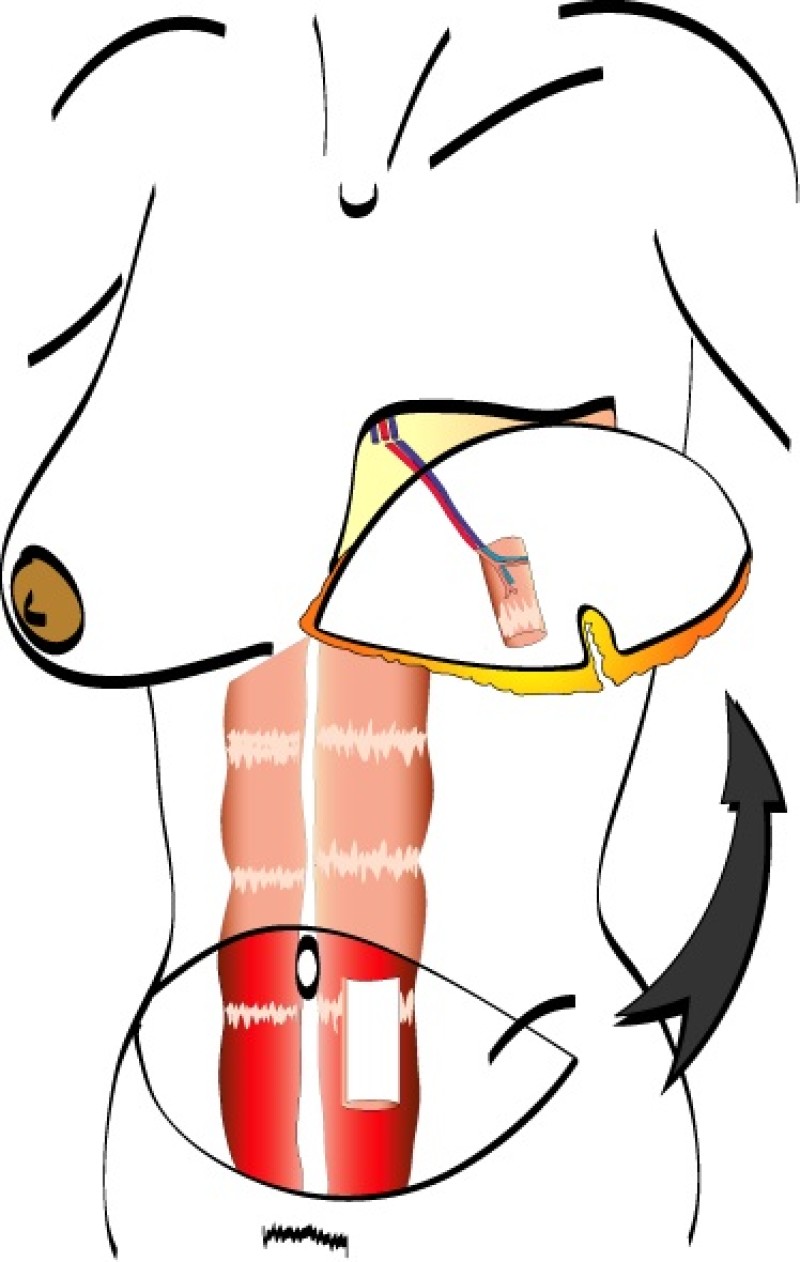

Fig. 2 (a)

Fig. 2 (b)

Fig. 2 (a) The muscle-sparing free TRAM flap gets its normal blood flow from the same vessels coming from the groin (the inferior epigastric artery and vein); (b) Similar to the free TRAM flap, these vessels are hooked up to recipient vessels through microsurgery. |

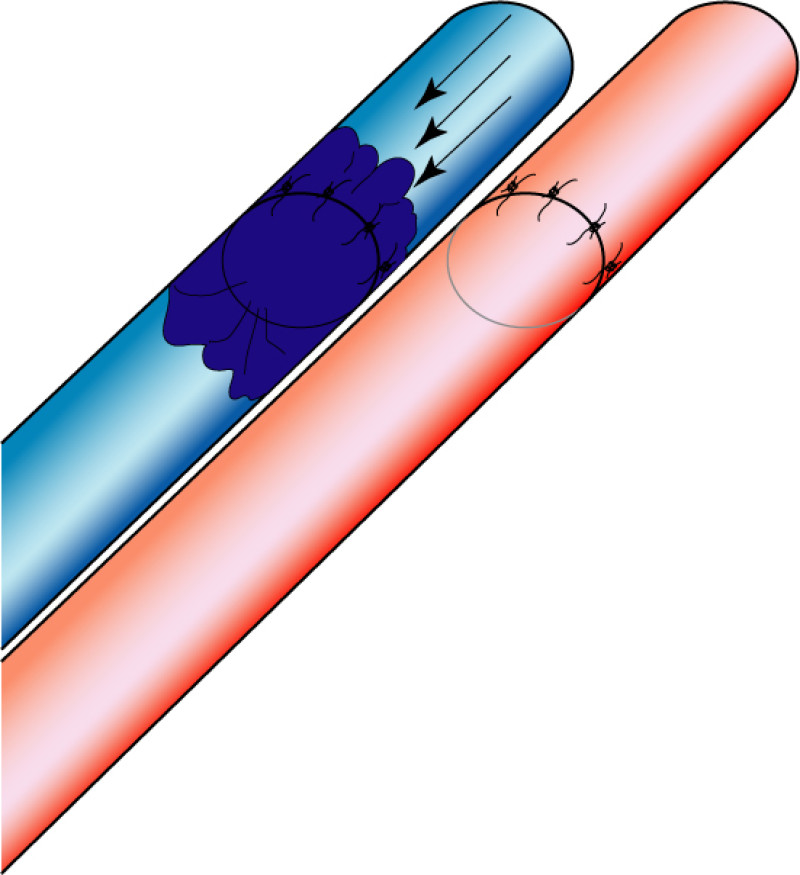

It is the microsurgical connection or anastomosis that can potentially give rise to problems. A blood clot (thrombosis) occurs at this site in approximately 3 to 4 % of patients. It most frequently happens during the first 48 hours following surgery and therefore every patient is closely monitored by specialized nurses during this period. If a thrombosis occurs, a further operation is required to remove the clot and re-establish the blood flow. If the clot cannot be removed this leads to complete loss of the flap (0.5 to 1% of cases).

However, in addition to reducing the abdominal wall deficit, the free TRAM has an improved blood supply because there is no twisting of the flap during transfer. It is also easier to create an aesthetically pleasing breast shape.

Incidence of complications

Pedicled TRAM | Free TRAM | |

Return to theatre | 2 | 5.1 |

Partial Flap Necrosis | 11.1 | 4.3 |

Fat Necrosis | 6.4 | 4.7 |

Total Flap Loss | 1.3 | 2.1 |

Seroma | 8 | 3 |

Haematoma | 2.2 | 2.3 |

Infection | 4.1 | 1.1 |

Abdominal Bulge | 6.9 | 3.8 |

Abdominal Hernia | 3.4 | 2.9 |

References

Blondeel N, Boeckx WD, Vanderstraeten GG, Lysens R, Van Landuyt K, Tonnard P, Monstrey SJ, Matton G. The fate of the oblique abdominal muscles after free TRAM flap surgery. Br J Plast Surg. 1997;50(5):315-21.

Larson DL, Yousif NJ, Sinha Rk, et al. A comparison of pedicled and free TRAM flaps for breast reconstruction in a single institution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:674-680.

Blondeel PN, Arnstein M, Verstraete K, Depuydt K, Van Landuyt KH, Monstrey SJ, Kroll SS. Venous congestion and blood flow in free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous and deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(6):1295-9.

Kroll SS. Fat necrosis in free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous and deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:576–583.

Blondeel PN. Venous augmentation of the free TRAM flap. Br J Plast Surg. 2002;55(1):87.

Man LX, Selber JC, Serletti JM. Abdominal wall following free TRAM or DIEP flap reconstruction: a meta-analysis and critical review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(3):752-64.

Blondeel PN. Discussion: perfusion-related complications are similar for DIEP and muscle-sparing free TRAM flaps harvested on medial or lateral deep inferior epigastric artery branch perforators for breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(6):590e-2e.

Blondeel PN, Neligan P. Are bilateral TRAM flaps as good as bilateral DIEP flaps? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(2):590-1; author reply 591-2.

3. DIEAP Flap

Introduction

Since the evolution of plastic surgery, the lower abdomen has been an abundant and reliable source of well vascularised material. Originally, pedicled and tubed flaps were used to transfer this tissue to distant sites. The lower abdominal skin and fat was then discovered to be the ideal material for breast reconstruction and the transverse rectus abdominis musculo-cutaneous (TRAM) flap was introduced. The pedicled TRAM was subsequently replaced by the free TRAM because this offers better tissue perfusion from the dominant deep inferior epigastric system.

In the mid-1980’s, it became apparent that a single large peri-umbilical perforating vessel (fig.1) originating from the deep inferior epigastric artery was adequate for complete flap perfusion. This was confirmed in 1989 when Isao Koshima (Tokyo) first published two cases of “deep inferior epigastric skin flaps without rectus abdominis muscle”. Robert Allen (New Orleans, U.S.A.) and Phillip Blondeel (Gent, Belgium) then expanded the use of the deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEAP) flap for breast reconstruction and technically refined the procedure. The DIEAP flap quickly gained popularity as it produced comparable results to the TRAM flap but without the added morbidity of rectus abdominis muscle sacrifice.

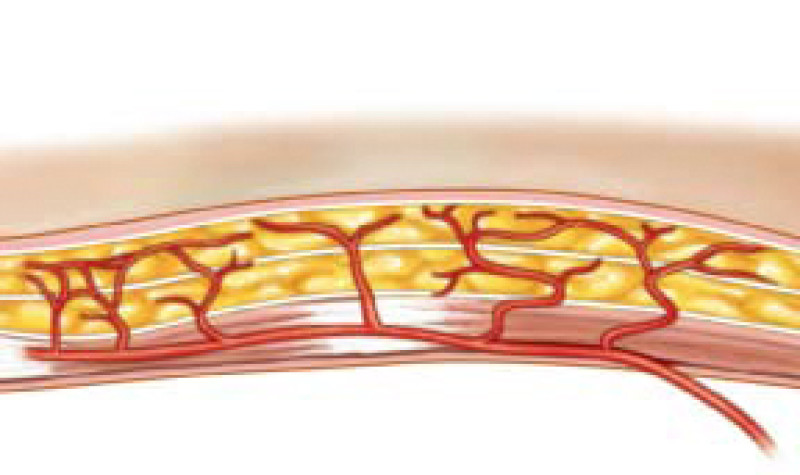

Fig. 1: Schematic representation of perforator vessels traversing muscle to reach the overlying fat and skin. |

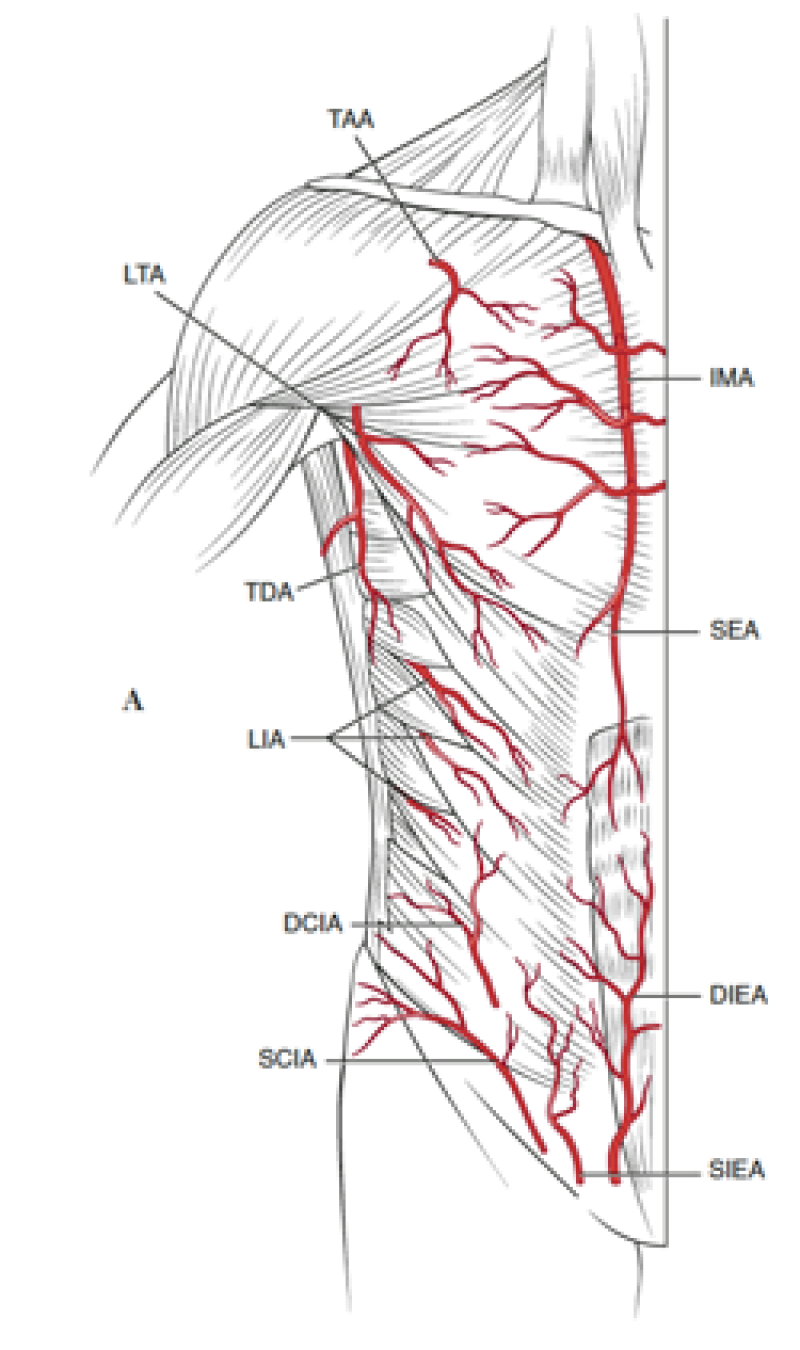

The lower abdomen is supplied by both the deep and superficial inferior epigastric arteries and surgeons then transferred the same anatomical unit based on the superficial inferior epigastric artery (fig. 2). James Grotting (Birmingham, U.S.A.) in 1991 was the first to use the superficial inferior epigastric artery (SIEA) flap for breast reconstruction. The SIEA flap has even less donor site morbidity than the DIEAP flap, as the fascia overlying the rectus abdominis muscle is not breached.

Fig. 2: Vascular anatomy of the trunk: DIEA: Deep Inferior Epigastric Artery; SIEA: Superficial Inferior Epigastric Artery; SEA: Superior Epigastric Artery; IMA: Internal Mammary Artery (recipient vessels for free flap surgery). |

In this era of rapidly evolving scientific discovery, these perforator flaps represent the current gold standard in soft tissue reconstruction. They offer the best potential results to patients with the least donor site morbidity. In our opinion, the DIEAP and SIEA flaps should therefore be the first reconstructive options considered for breast reconstruction in appropriately selected patients.

DIEAP - Surgical Technique

The DIEAP and SIEA flaps consist of skin and fat from the lower abdomen. In contrast to the TRAM flap, no fascia or muscle is sacrificed when these flaps are harvested. As a result, there is no functional loss or weakening of the anterior abdominal wall.

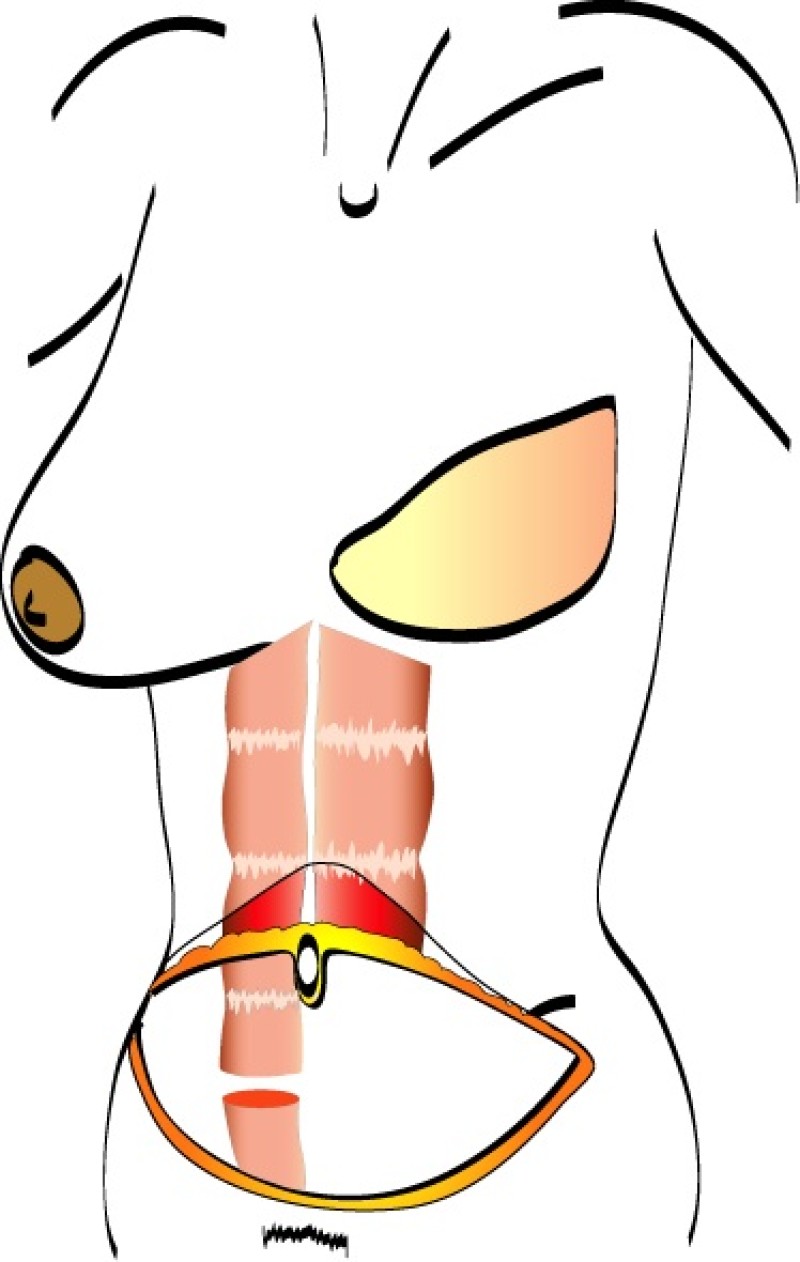

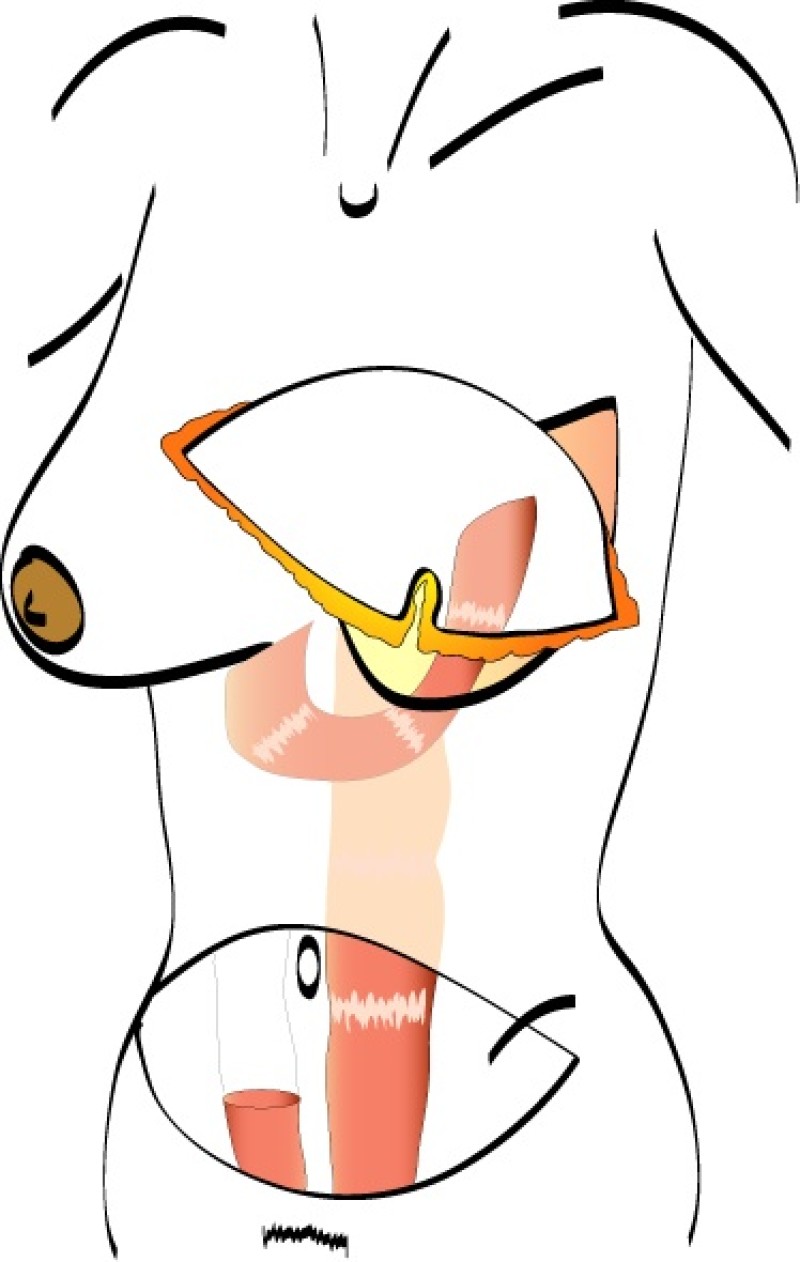

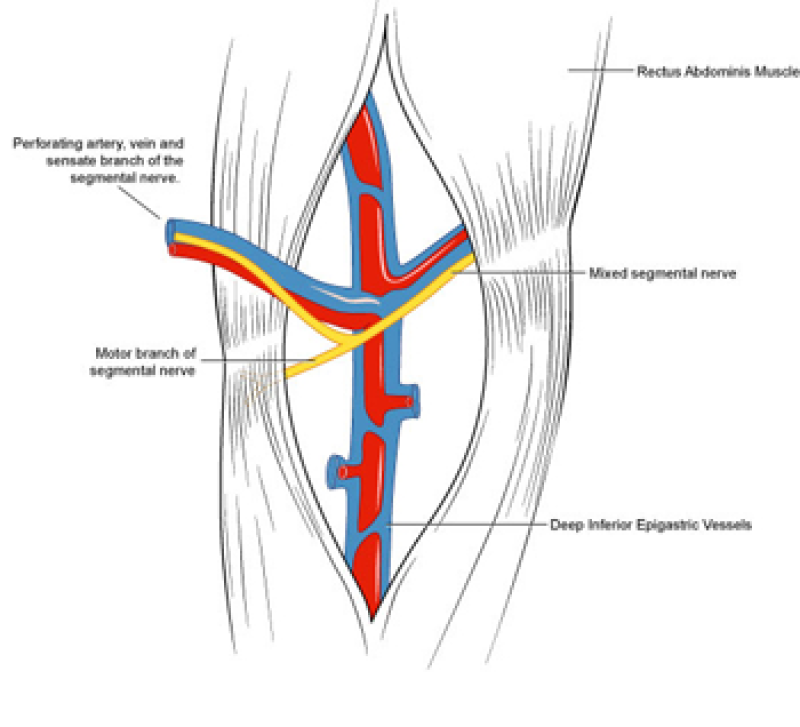

During DIEAP flap dissection, the rectus abdominis muscle is opened along the line of its fibres (fig. 1). The perforating vessels which pierce the muscle to supply the overlying skin are then freed from their surrounding connective tissue (fig. 2). The rectus abdominis muscle is therefore kept intact and its blood supply, nerve supply, function and strength are all preserved.

Fig. 1(a)

Fig. 1(b)

Fig. 1(c)

Figure 1: Schematic representation of a DIEAP flap (a, b) and the resulting scar on the lower abdomen (c). |

Fig. 2

Fig. 2: Splitting the rectus abdominis muscle in the line of its fibers exposes the underlying vessels and nerves. |

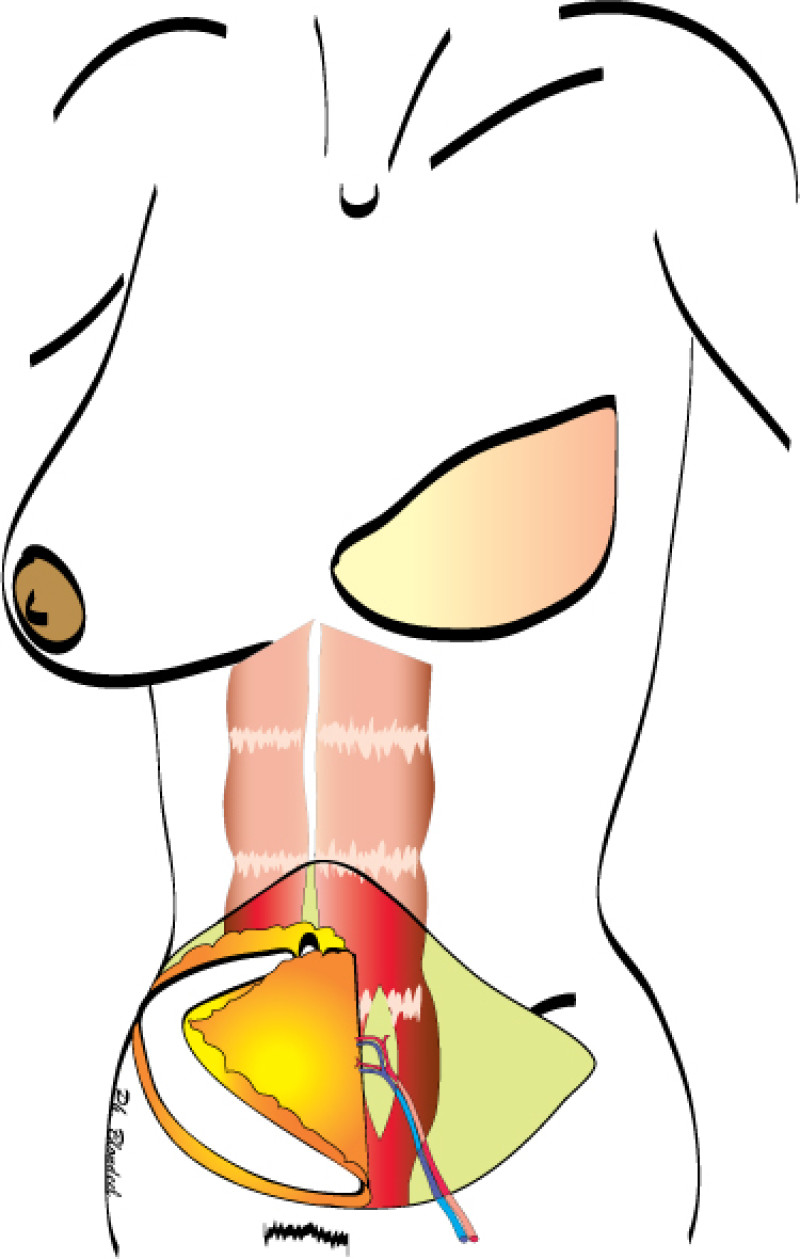

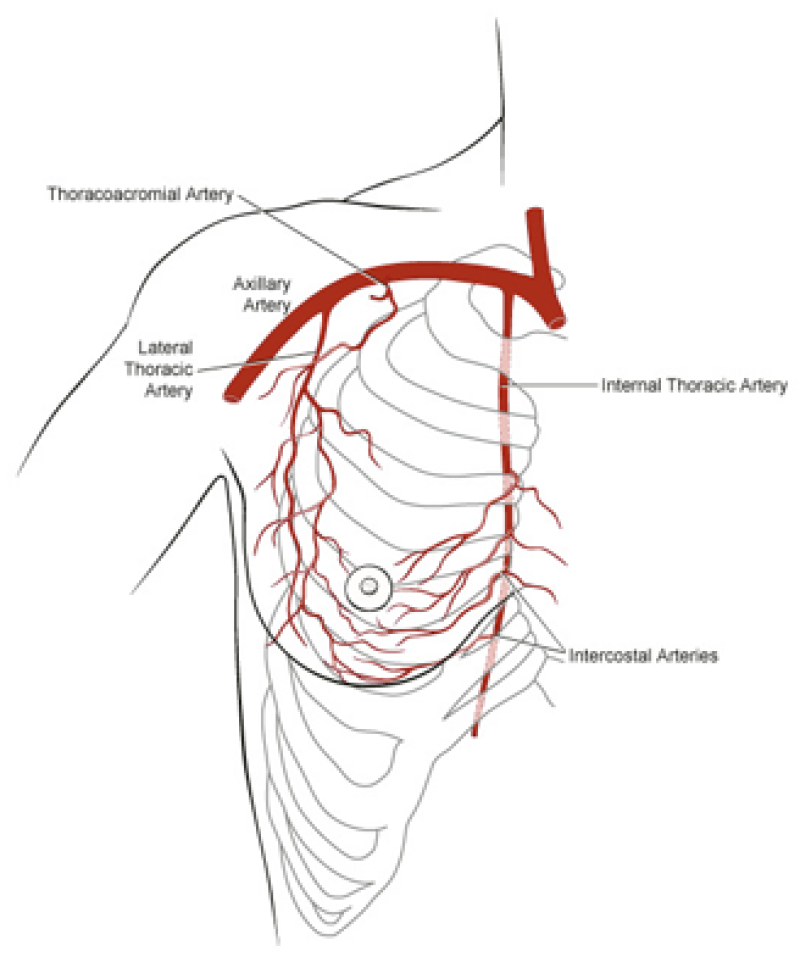

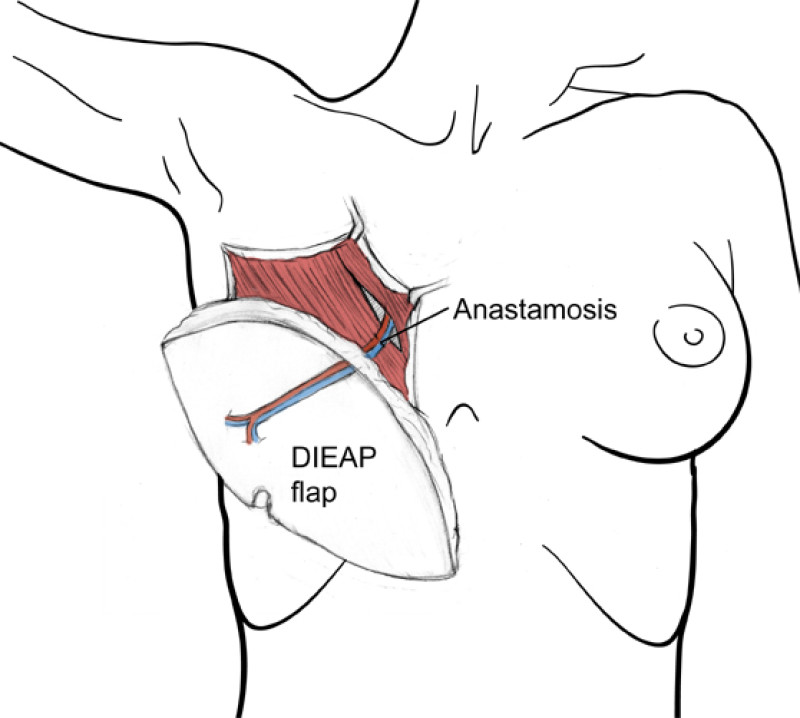

The deep inferior epigastric vessels are then divided in the groin. This temporarily stops the blood supply to the flap but the tissue can survive like this for 6 hours. The flap is then transferred to the chest wall and positioned over the mastectomy defect. An artery and vein have simultaneously been prepared next to the sternum at the level of the 3rd or 4th rib. These are the internal mammary or internal thoracic vessels (fig. 3), comparable to the deep inferior epigastric vessels, with dimensions of between 1 and 3 mm. Both sets of arteries and veins are then sutured together using an operating microscope. Once connected, blood flow is restored and the flap quickly recovers.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3: Possible vessels that serve as recipient blood vessels to connect the flap to. |

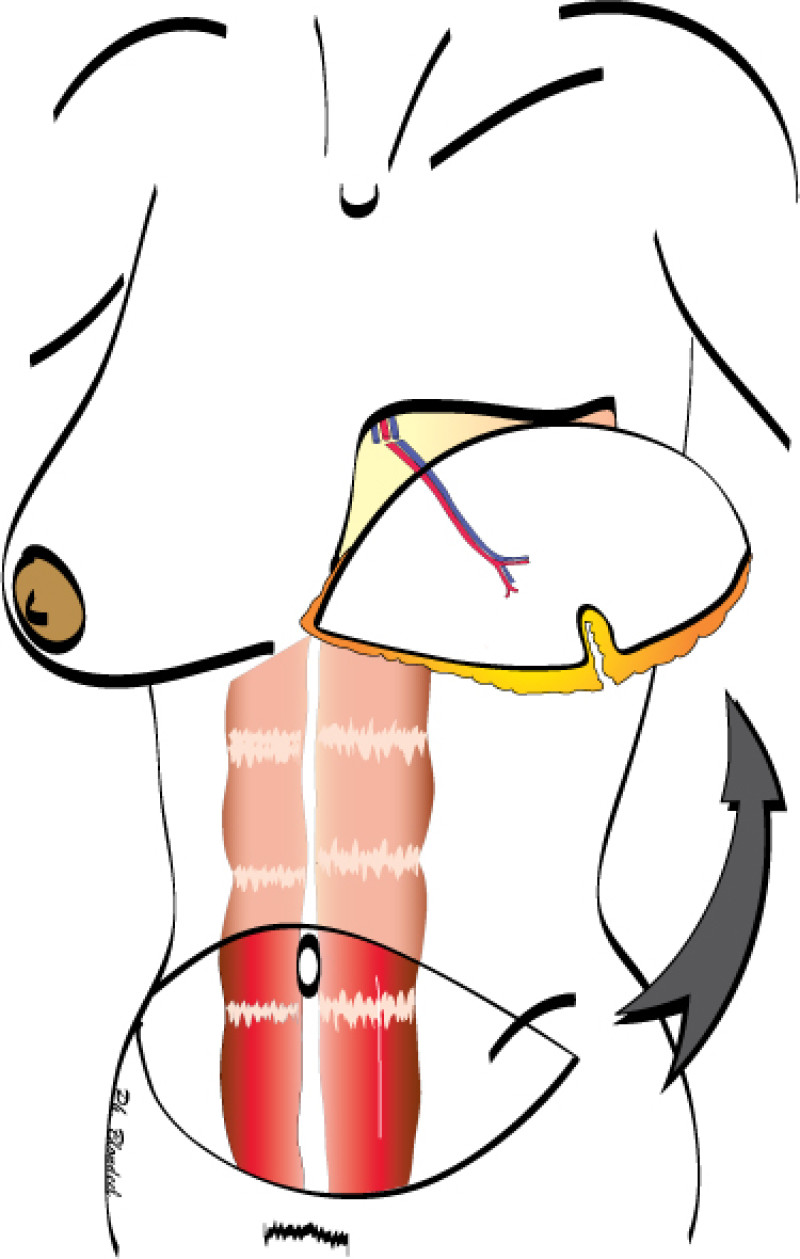

The final step is to shape the abdominal tissue into an aesthetically pleasing three-dimensional breast, which matches the contralateral side. In a delayed breast reconstruction, there will still be a scar across the new breast, but below this there will be abdominal skin and subcutaneous fat (fig. 4 a-d). A further scar is present along the crease where this abdominal tissue meets the chest wall. In an immediate breast reconstruction, the scars will vary from a nipple-shaped circle to a larger oval, depending on the extent of surgery required to safely remove the tumour. In both forms of breast reconstruction, the abdominal scar lies above the pubic area, passing from hip-to-hip. There is also a scar around the umbilicus (belly button).

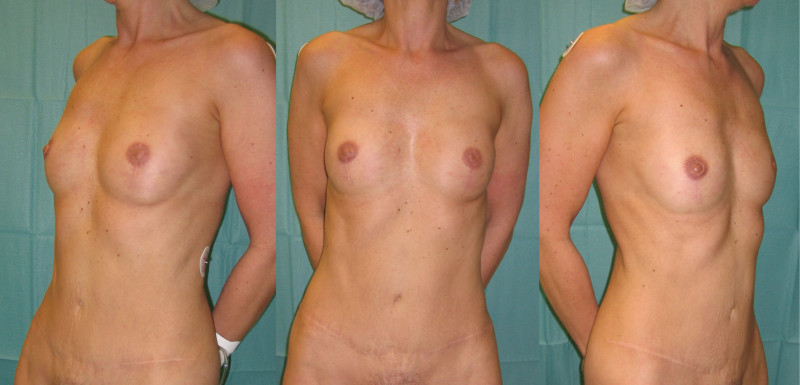

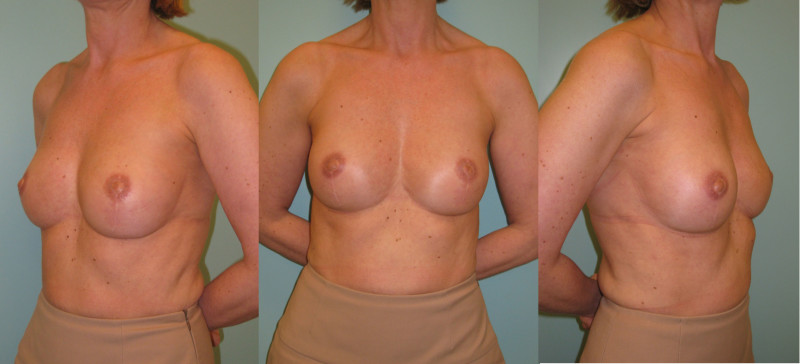

Figure 4: Schematic representation of secondary breast reconstruction with a DIEAP flap. |

At the donor site, the fascia covering the rectus abdominis muscle is repaired. This closure is tension-free, as no fascia has been resected and synthetic mesh is never required. The remaining skin is then undermined up to the costal margin, the umbilicus brought out again, suction drains inserted and the abdomen closed in layers. Finally, skin adhesive (surgical glue) is applied to the incisions, providing an additional layer of support to the wounds and also acting as a waterproof dressing.